Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Through April 6

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 28, 2013

Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Through April 6

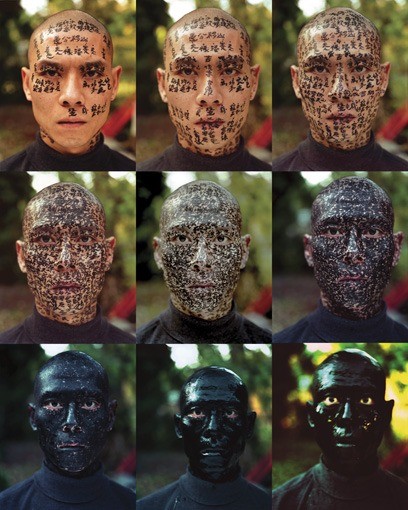

The most interesting work we have seen in recent years has been created by Chinese artists. Several of these exhibitions have been presented by Mass MoCA including Huang Yong Ping, Cai Guo-Qiang, and the hit of this past season Xu Bing. In February we saw the traveling exhibition of Ai Weiwei in Washington, D. C. at the Hirshhorn Museum. The endurance based performances and related photographs by Zhang Huan are familiar from museum and gallery exhibitions.

The fascinating, informative and compelling special exhibition, Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China, which is on view through April 6 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art presents them (minus Ping) in a selection of 70 works by 35 artists.

The curator Maxwell K. Hearn, head of the department of Asian art and an expert in Chinese painting and calligraphy, has opted to install the work in a series of galleries for the permanent collection.

There is a plus and minus to this strategy. It is generating more traffic through relatively untraveled galleries. But the general visitor has to know they are there and seek them out.

Significantly, just days after the opening, there were a number of people viewing the exhibition. The attendance was considerably less than in the special exhibition galleries. A good percentage were visitors of Asian heritage with a predilection of interest in the genre of work. This was not the case for the Mass MoCA and Hirshhorn exhibitions which drew large crowds with diverse demographics.

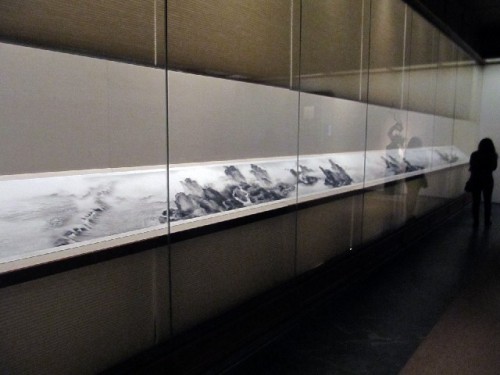

Installing Ink Art in the permanent collection galleries proved to be cost effective. This entailed recycling vitrines for long scrolls and large kakemonos. Many of the artists in the exhibition work in these traditional formats. So the display cases, which would be expensive to replicate, are efficiently recycled.

Although intrigued and moved by contemporary Chinese artists I am not an expert in the field. There is always more to learn and the sense of exploring the tip of the iceberg. The current Met show represents a the daunting learning curve.

Lacking greater depth and exposure it is risky to make general observations about contemporary Chinese art. We spent a week in Shanghai some years ago. That’s better than nothing. But suggests a tourist discussing the United States based on a week in New York, Chicago, Vegas or LA. China is a vast nation with an enormously diverse culture. So far we know only what has been shown in the West.

Even though sketchy I find contemporary Chinese art far more engaging and fulfilling than the majority of Western work shown by museums and galleries.

Nor am I alone.

Anyone who saw the Phoenix installation by Xu Bing in the cavernous Building Five at Mass MoCA came away utterly floored.

What we see in the Met exhibition is an uncanny confluence between deeply rooted, ancient traditions often conflated with Western modernism. Even during the repressive Maoist era of the Cultural Revolution young artists were grasping for information about Duchamp, conceptualism and Beuys. That shows up literally in works in this exhibition.

There was a lot of evidence of this in the dada/ conceptualist works of Huang Yong Ping in his Mass MoCA exhibition. Books, magazines and reproductions of avant-garde works were circulated clandestinely among artists. One installation was a dimly lit reading room of the material. Other works entailed literally masticating the precious printed texts in laundry machines. They were reduced to pulp which was then used as a material for creating sculptural pieces. It was an amazing metaphor for how Chinese artists, under the repressive radar of the communist regime, were absorbing modernist influences.

Many of the strategies of Ai Weiwei entail reversing the momentum of repression. When the government mounted cameras to spy on his studio he created simulacra carved from marble. His work includes documentation of their surveillance, attacks and acts of violence against him. In an incident when police swarmed into his home the artist sustained a head injury that almost killed him. His X Rays were incorporated into works of art.

There is a compelling sense of sincerity to the work. So much of Western art that one encounters at biennials, art fairs, museums and galleries is market driven, pretentious, derivative and cynical. We never quite know whether to laugh with or at mega artists from Jeff Koons, to Matthew Barney. It’s a struggle to understand why there is a retrospective for Christopher Wool at the Guggenheim.

Although numerous studio assistants and fabricators are employed to create the industrial scaled works of Ai Weiwei and Xu Bing the result never feels soulless or commercial. How long that remains true is yet to be seen. As the work claims an ever larger market share and critical status will that inevitably corrupt artists and weaken their vision?

For now the adversity of creating under a Marxist regime prevails as a critical factor. Ai Weiwei continues as a political prisoner under house arrest. Others come and go, like Xu Bing, if they play by the rules. His resistance is more overt but no less potent.

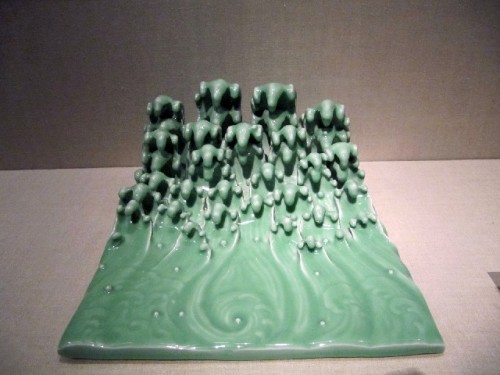

In significant ways the Met show was flawed. Start with the misleading title Ink Art. The traditional use of the brush is just an aspect of the project. There are also abundant examples of sculpture, furniture, ceramics, and photo based works. It results in a more diverse show.

There is a lot of humor. We encounter the look of traditional ink brush work, bimo, but with surprising elements. Photographs are collaged to create scrolls and kakemonos

Perambulating through the installation there were fits and starts, evoking mental explosions of the seemingly familiar and traditional juxtaposed with the esoteric and arcane.

There was a disproportion between the well known artists given more space and works than just a single work or glimpse of the emerging artists.

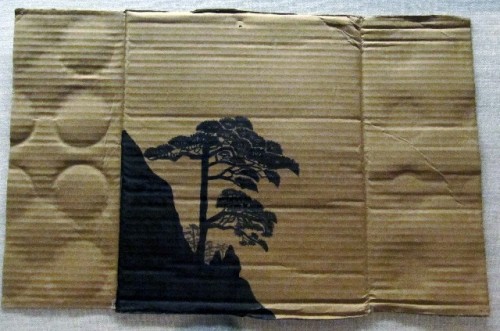

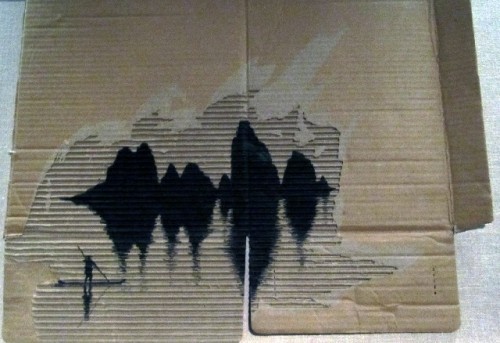

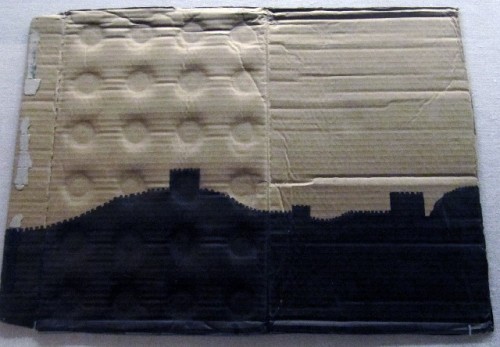

In the Beautiful Dream series by Duan Jianyu we observe a familiar view of a monochrome, black, woodblock printed onto the surprising support of fragments of cardboard boxes.

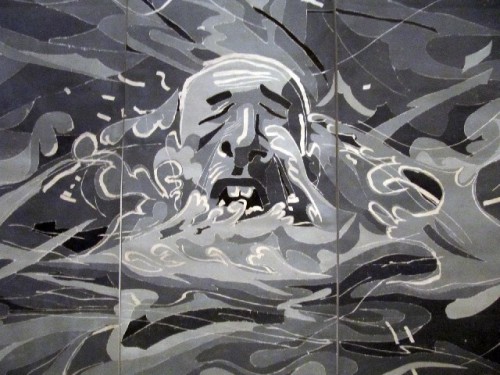

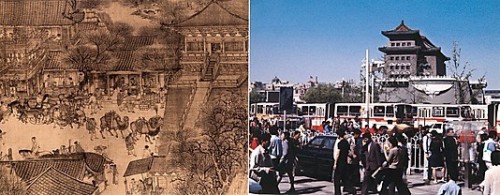

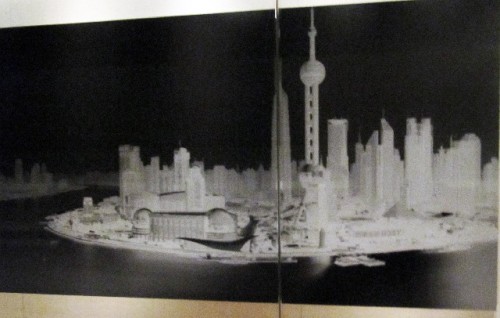

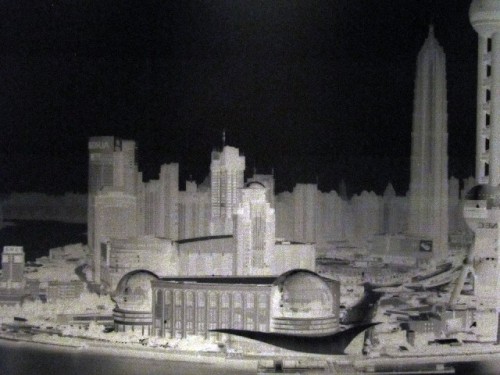

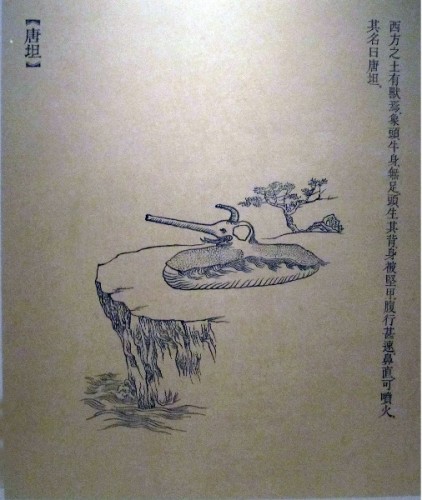

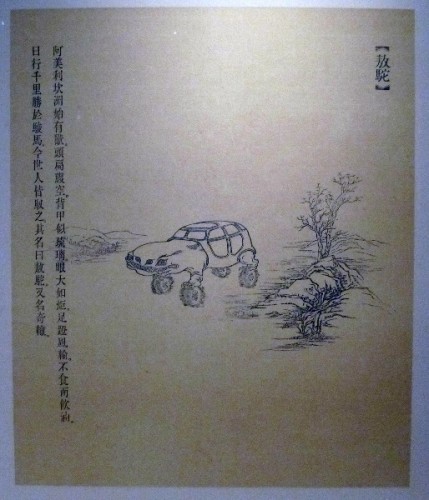

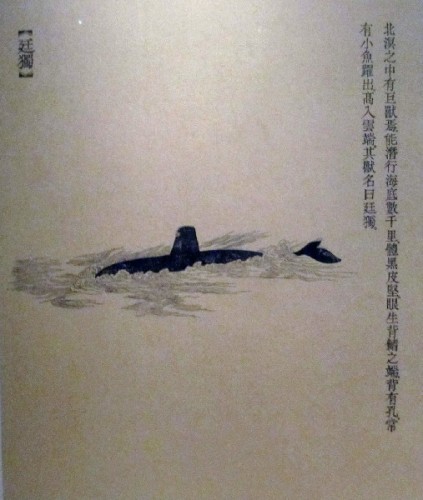

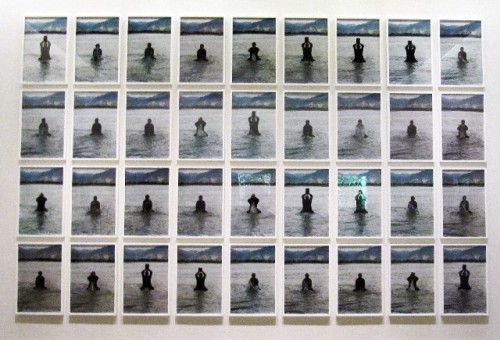

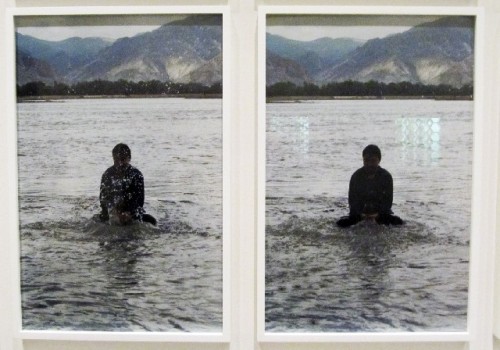

Fang Lijun in 2003.3.1, a large grisaille painting, humorously depicts what appears to be a drowning man. The panoramic, camera obscura, black and white, ghostly view of Shanghai by Shi Guorui brought back memories of our time in that city. View of Tides by Yang Yongliang, with its traditional brushwork, would fit well in the Met’s permanent collection. Three small works by Qiu Anxiong from his New Classics of Mountains and Seas have witty anthropomorphic surprises. Is that a car, jeep, or some kind of monster animal?

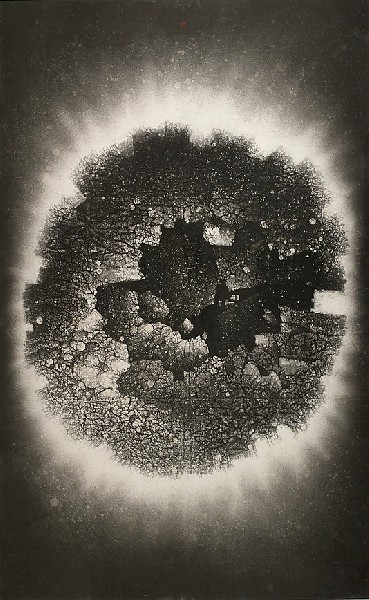

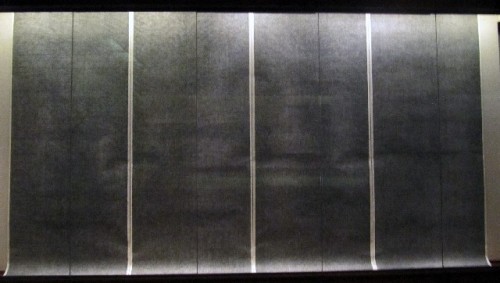

There is compelling, dense, minimalist abstraction in the gorgeous surface of the large 100 Layers of Ink by Yang Jiechang. Cai Guo-Qiang is represented by an inked scroll and videos with a conceptual take on Project to Extend the Great Wall of China by 10,000 Meters: Project for Extraterrestrials No. 10.

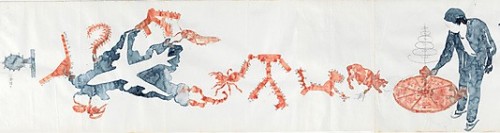

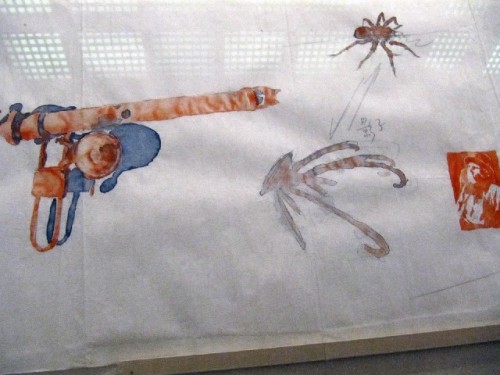

Long Scroll by Huang Yongping is a loosely painted watercolor with elements evoking an airplane, a work by Duchamp, and cryptic icons of Beuys.

Curators, gallerists and collectors will approach this exhibition as a check list for future possibilities. We are likely to see more of all of these artists.

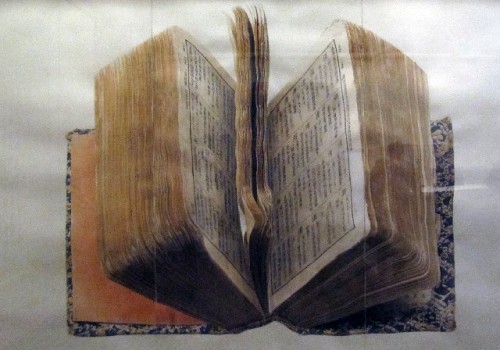

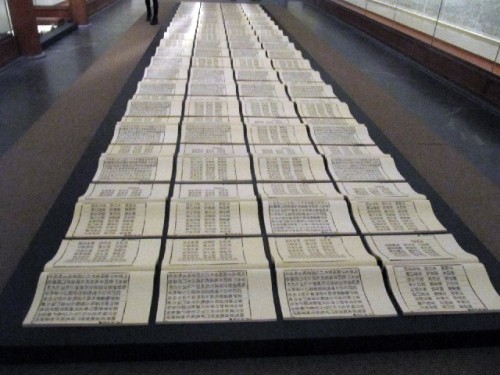

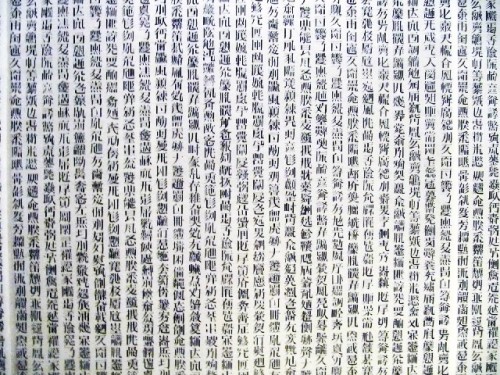

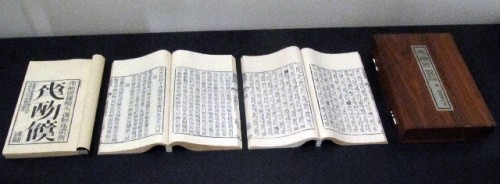

For me it was compelling again to view Xu Bing’s 1991 Book From the Sky. Installed at the Mass College of Art some years ago it represented my first exposure to contemporary Chinese art. It takes up an entire room. There are long sheets of printed paper forming arcs above and rows of books with calligraphy below. The flanking side of the space entail wall cases with large sheets of calligraphy.

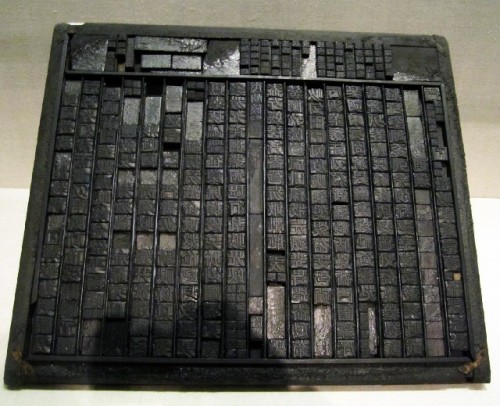

Another gallery displays his carved calligraphy slugs that, when locked into a grid frame, are used to print pages of a book. The artist has created a vast vocabulary of ersatz calligraphy which, on close inspection, depict universal semiotics.

Ink Art: Past as Present in Contemporary China is the most important and insightful exhibition of contemporary art currently on view in any New York museum.