Xu Bing Language Lost

Mass College of Art 1995

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 24, 2012

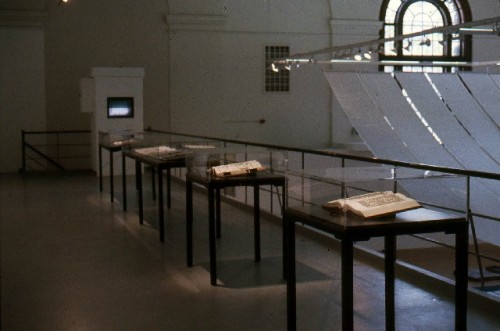

There was an imposing grandeur with banners suspended the length of the vaulted upper gallery of the Massacusetts College of Art Gallery, as well as, an intimately absorbing array of vitrines with books in ersatz calligraphy. There were a number of pedestals with books, objects and a stack of Boston Globe newspapers all embedded in webs spun by silk worms.

The exhibition Language Lost (18 September to 22 December, 1995) by Xu Bing was our first exposure to a seminal generation of Chinese artists.

Mass MoCA has installed the formidable pair of enormous, suspended birds Phoenix which will remain on view in the vast space of its Building Five for the coming year.

This occasion evoked another view of a landmark exhibition which was indeed ahead of the curve of global attention in the art world.

The project was so unique and intriguing that I recorded it with a set of slides. The intention was a part of an ongoing commitment to chronicle contemporary art both for my own information and a resource for teaching.

Today, the images are of enormous historical relevance as they illustrate a phase of the artist’s work and development on view at Mass MoCA.

It highlights Bing’s origins in traditional calligraphy and a concern for morphing global language and communication.

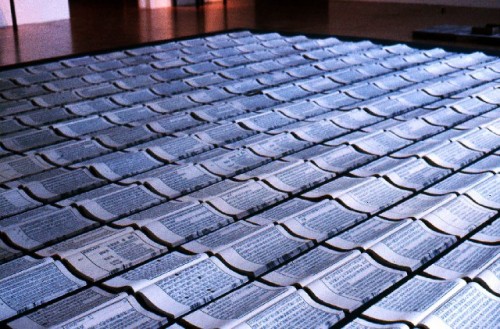

Underneath the suspended banners was a grid of 200 books opened in such a manner that they provided a rippling sea of text. Like most American visitors I assumed that they provided a narrative that I could not read.

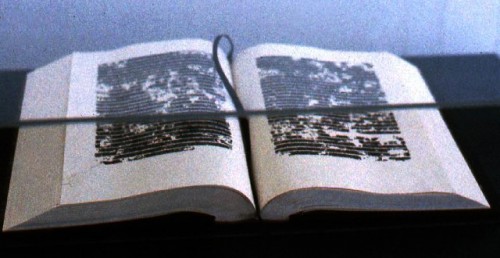

The irony, however, is that they would be just as inscrutable to a Chinese viewer. The books and banners were hand printed with some 4,000 carved invented characters. They were derived from a series by Bing called A Book from the Sky. The artist started the project in China and was then resident in the United States where he was awarded with a MacArthur Fellowship.

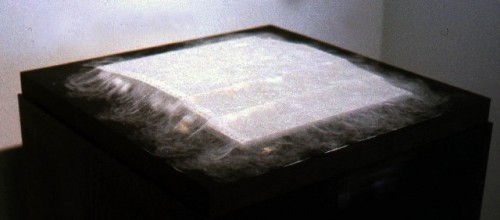

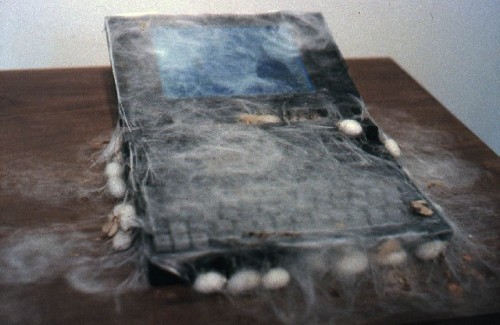

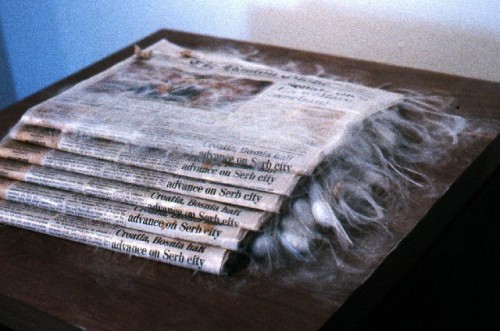

There is a balcony in the gallery that looks down into the exhibition space. Bing presented a series of displays and pedestals. On top of which was placed a stack of Boston Globes, a French dictionary and a computer laptop. These were covered with webs woven by live silk worms.

The ersatz cobwebs evoked the sense of a slow passage of time and its decay. Or, in this context Language Lost.

The artist is interested in the iconography of text. To master reading and writing Chinese entails memorizing and learning to depict thousands of individual characters.

Fast forwarding from ancient calligraphy to modern signs and symbols subsumes into the philosophy of semiotics. The artist in interested in the use of universal symbols. One context is how we find directions when visiting international airports. It is the linguistic technology of providing universal access to information.

Toward this end the artist creates landscapes with ersatz Chinese calligraphy, which when viewed with attention, reveal text readable in English.

In the current Mass MoCA exhibition there is a light box recreating a Chinese masterpiece. A reproduction of the original is displayed for comparison.

Walking around to the back of the light box one is surprised to see that the image has been created by casting a shadow over an array of found objects. These ephemera have been employed to create the illusion of a reproduction of an ancient Kakemono.

In the world of Xu Bing what you see is not what you get.