Slaves and Slaveholders of Wessyngton Plantation

Tennessee State Museum Through August 31

By: Charles Giuliano - May 12, 2014

Slaves and Slaveholders of Wessyngton Plantation

Tennessee State Museum

Nashville, Tennessee

February 11 through August 31, 2014

During a recent road trip we visited plantations and mansions in Natchez, Mississippi. During a tour of Longwood, which remained unfinished because of the outbreak of the Civil War, the guide referred to the “workers” and “helpers” of Dr. Nutt.

The emphasis was on architecture and not the human misery that spawned these grand and elegant Southern homes. Longwood was funded by five plantations and the hard labor of as many as 800 slaves.

In Charleston and Louisville we encountered metal relief signs that document slavery in those cities. I don’t recall such signage in Savannah.

It is a troubling aspect of American history that presidents owned slaves including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Martin Van Buren (not while president), William Henry Harrison (not while president), John Tyler, James K. Polk, Zachary Taylor, Andrew Jackson, Andrew Johnson (not while president). This legacy is downplayed in visits to Washington’s Mt. Vernon, Jefferson’s Monticello and Jackson’s Hermitage. Both Jackson and Jefferson owned about 200 slaves each.

When Washington was twelve years old, he inherited ten slaves; by the time of his death, 316 slaves lived at Mount Vernon, including 123 owned by Washington, 40 leased from a neighbor, and an additional 153 "dower slaves." In his will the slaves were to be freed following the death of his widow. She did this while still living.

Northern framers of the Constitution deferred to the south on the matter of slavery. Without this concession there would have been no union.

Touring the beautiful cities and monuments of the south evokes complex emotions. The experience in Natchez was particularly unsettling and creepy. As a friend from Charleston put it “nothing has changed.”

It was fascinating in this context to visit the Tennessee State Museum and meet for an interview with a curator Rob DeHart and publicist Mary Skinner. The museum has mounted a well researched exhibition that focuses on the surviving documents of an enormous plantation and presents a dual chronicle of both its slaves and their owners. It is a non polemical, meticulously researched project that invites visitors to view the reality of slavery and draw their own conclusions. For this exhibition families of both slaves and slave owners came together to tell their stories. What follows is a statement by the museum.

The exhibit, Slaves and Slaveholders of Wessyngton Plantation, looks at the lives of both enslaved African Americans and their white owners on the 13,000 acre plantation in Robertson County, Tennessee.

Through first and third person accounts, the exhibit reconstructs the lives of several enslaved people, providing names, faces, and the details of what happened to them before, during, and after the Civil War.

Among the slaves profiled in the exhibit is Jenny Blow Washington. The founder of Wessyngton Plantation, Joseph Washington, purchased 10-year-old Jenny and her sister from a Virginia planter in 1802. The sisters traveled to Wessyngton Plantation in Tennessee with Washington, never to see their mother again. Although slaves could not legally marry, Jenny had a lifelong relationship with a slave named Godfrey Washington and gave birth to at least nine children. Jenny and her family performed the chores involved with maintaining the large Washington house. Her known descendants number in the thousands.

Most museum exhibits cannot provide an in-depth look at individual enslaved people because there is little information available. Because of fortunate circumstances of record-keeping and photography by the Wessyngton owners and a wealth of research and oral history by one of the slave descendants these otherwise forgotten people are brought to life.

The plantation was established in 1796 by Joseph Washington, who moved to Tennessee from Virginia, and was later inherited by his son, George A. Washington. The Washingtons, through their business dealings, became wealthy, owning not only Wessyngton but also property and slaves in Kentucky. Wessyngton was one of the largest plantations in Tennessee in 1860 and the largest producer of tobacco in the U.S. In 1860, the Washingtons were one of the wealthiest families in Tennessee.

The Washingtons, with two exceptions, never sold their slaves, and by 1860 owned 274. Slave families at Wessyngton had three to five generations living together, remarkable in a system that often separated enslaved families, including selling children away from their parents.

The Washingtons, who held on to their wealth during and after the Civil War, retained detailed records about their plantation and slaves. These records, along with letters and diaries, survived into the 20th century and were later donated by Washington family descendants to the Tennessee State Library and Archives (TSLA).

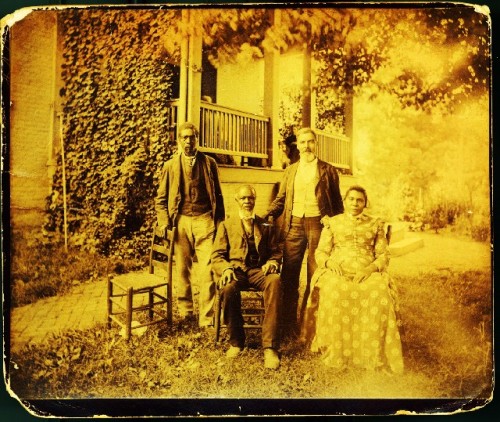

These records were researched at TSLA by a descendent of the Washington slaves, John Baker, Jr., who had seen a photograph of the former Wessyngton slaves in his seventh grade history book. His interest was stimulated when his grand mother told him that he was related to them. He later met a Washington descendant, who invited him to visit Wessyngton.

John said “visiting Wessyngton was like stepping back in time.” There he saw a portrait of his great, great grandfather hanging on the wall, along with portraits of other slaves.

As an adult, Baker spent years going through the Wessyngton records at the TSLA. He also interviewed many individuals, ranging from 80 to 107 years old, who were children or grandchildren of the Wessyngton slaves. Baker wrote The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation, about his lifelong research. This book inspired the Wessyngton exhibition.

Baker located photographs and drawings commissioned by the Washington family of the former slaves who remained on the plantation after the Civil War. These drawings and photographs remained in the Washington and slave descendant families.

The exhibit also looks at the important roles of the white women of the big house They supervised the production of finished clothing for the family and slaves. Such a large labor force meant hundreds of garments had to be produced each year. They also oversaw the food rations for the slaves which totaled 42,000 pounds of pork per year.

At the end of the exhibit, a section called “Legacies” traces what happened to several of the slaves after the Civil War.

Between 1841 and 1863 some 21 slaves including five women were whipped for various offenses. These included running away, losing or damaging tools or not working hard enough. Plantation owners balanced cruelty with incentives. The slaves had Saturday afternoon and all day Sunday off. The Washingtons didn’t sell their slaves. Except for two slaves that made repeated attempts to run away Davy White and a man known only as Henry.

Rob DeHart It is most unusual that so many records and documents survive which is why it was possible to put this exhibition together. A lot of the furniture and artifacts on view are from our collection. When the Washington family sold Wessyngton in 1983 they had an auction. Things went all over the place. Some things we brought back and some we couldn’t.

One example is this portrait of George A. Washington when he was 15-years-old. It was painted in about 1830. It was painted by Washington Cooper who was a very popular portrait artist in Nashville.

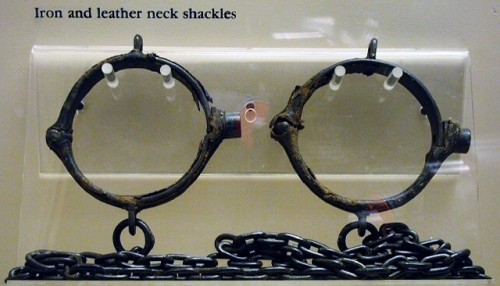

The other pieces we base on receipts in the Washington papers. For example this is a list of household items which George’s wife made during the Civil War. They were trying to protect their items from looters during the Civil War. They crated them and shipped them to Louisville. Ironically the warehouse burned down so they lost them anyway. But we are able to take these lists and match them up. We also put the shackles in there because we always want visitors to see the connection between slavery and these luxury items.

Charles Giuliano Because as you say the Washingtons sold only two slaves we would assume that through a natural process the population increased.

RD Yes. These are lists of all of the slaves that they acquired either through purchase or birth.

CG Looking at the prices why is one 500 and another 100? (records on display)

RD Well this is 100 English pounds in 1802. So some of the currency depended on where you bought them from. Some states were still using pounds. It also varied by the year.

CG Here I see $1,500.

RD That’s for six, a whole family. Here’s a purchase for $240 but this is the early 1800s. When the slave trade with Africa ended in 1808 it became much more expensive. It’s when it was supposed to end. There was still an illegal trade which went on.

Astrid Hiemer It became more expensive.

RD Yes, by 1823 a family of seven cost $2,600.

CG Considering that in 1861 the net value of their 13,000 acre plantation was $550,000 an individual slave was a relatively expensive investment.

RD It was a lot of money but for Washington it wasn’t too bad. The average person in American made perhaps $500 a year. That’s why only wealthy people could afford to own slaves. Most slave owners had between one and ten slaves. It was most unusual to have this number of slaves. Only a small percentage could afford that many.

CG How does Wessyngton compare to Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage which is also located in Tennessee?

RD Jackson had about 200 slaves on average. He was pretty much bankrupt by the end of his life. His son had to sell off things. Mostly it was a matter of mismanagement. He was gone for eight years in Washington. A lot of people blame his son but I don’t know if that’s really fair.

CG Jackson was one of the largest plantation owners.

RD Yeah. He ranked up there. Until the presidency he was a wealthy man. In the last years from what we know the Hermitage got kind of shabby.

CG Talk about the treatment of slaves.

RD I can show you some records on that. As historians are starting to look at it plantations were a negotiation between the owner and the slaves. The owners knew that if they were too brutal the slaves would not work and take off. Owners used different methods of control to try to keep them working. The slaves practiced resistance in ways that worked for them. In this part of the exhibition we show the task system, medical treatment and punishment.

The task system was when he or she finished a task they would be able to work on their own plots of tobacco. Those plots the owner would sell and take two thirds of the proceeds. It gave the slave incentive and a little bit of money. Here is a record from 1846 which shows how many pounds, who got money, and in some cases what they purchased with the money. That includes hats, shoes. I’ve seen records of pots and pans.

CG We also assume that they grew their own food.

RD Yes but the main meat, the pork, was provided. It’s something like 14,000 pounds a year which they consumed.

CG Not the hams but everything the masters wouldn’t eat like ears, feet, organs. Which of course became the basis of soul food. They say that you can eat anything off the hog but the squeal. Lyrics of a Blind Blake song says “Taters in the ashes, possum on the stove, save me the head and claws…”

RD Medical treatment which we see was another means of control. Of course keeping slaves healthy was in their best interest. Medical treatment at this time consisted of blood letting, blistering, leeching, induced vomiting and enemas. Medical treatment cost the slave owner about $300 a year. In our currency about $8,000.

CG For over 200 people that’s miniscule.

RD Of course punishment was a big part of it. We have numerous accounts of slaves being flogged, handcuffed, collared for various offenses. In the records you see references to “genteelly whipped, moderately whipped, severely whipped.” It depended on what they did. Of course running away produced the most severe punishment.

In terms of resistance they would ride work animals at night to wear them out. They would do anything to slow down the pace of work. They were very good at that; finding deceptive ways to slow down. To take some control of their lives.

A big part of this exhibition is about resistance and how they were able to build their own lives.

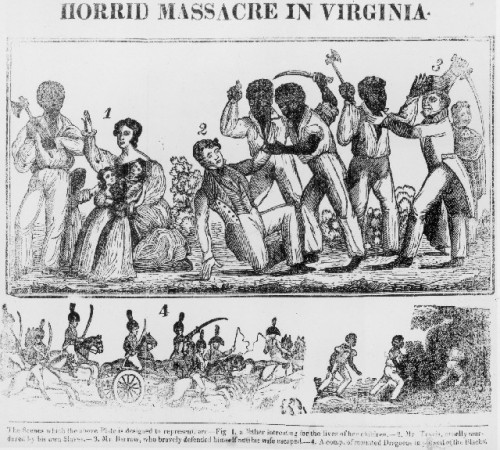

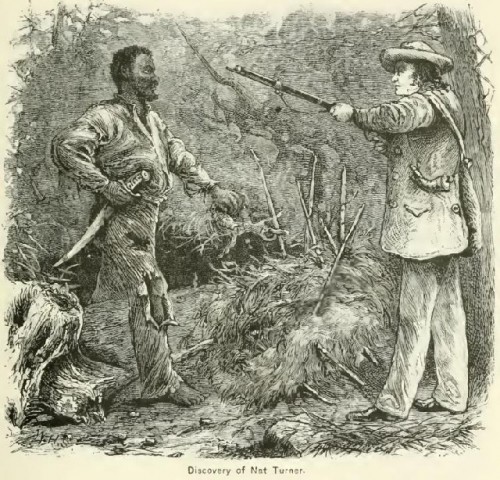

CG Where do Nat Turner and slave rebellions come into this exhibition?

(Nat Turner (October 2, 1800 – November 11, 1831) led a slave rebellion in Virginia on August 21, 1831 that resulted in 55 white deaths. Whites responded with at least 200 black deaths. He gathered supporters in Southampton County, Virginia. Turner was convicted, sentenced to death, and hanged. In the aftermath, the state executed 56 blacks accused of being part of Turner's slave rebellion. Two hundred blacks were also killed after being beaten by white militias and mobs reacting with violence. Across Virginia and other southern states, state legislators passed new laws prohibiting education of slaves and free blacks, restricting rights of assembly and other civil rights for free blacks, and requiring white ministers to be present at black worship services.)

RD Nat Turner changed the Tennessee constitution. Basically it made it almost impossible to emancipate a slave. If you emancipated one you had to leave the state because everyone was so paranoid about slave rebellions. The Washingtons were from Southhampton County which is where the Nat Turner rebellion occurred.

One thing the Washingtons did, which was kind of unusual, they didn’t allow religious services for their slaves. We speculate that because of Nat Turner they were so frightened of a gathering.

From oral histories we learn that the slaves did worship but they did it in secret.

CG I’ve always understood that it was in the interest of plantation owners to Christianize their slaves.

RD Exactly, which is why I find this strange. We’ve had to say in this exhibition that every plantation was unique. We learn some lessons from Wessyngton but you can’t apply them to slavery as a whole. It was different everywhere.

AH The Washingtons were British. When did they come?

RD The earliest ones came in the 1650s. They were very very distant relatives of George Washington.

CG What happened to the family after the war?

RD Amazingly they were more wealthy than before. Washington spent most of the war in New York investing. He was all for secession until Nashville was occupied by the Union Army in 1862. He was like a lot of owners who went from strict Confederates to “I’m just trying to save my property.” His son went to college in Canada. He and his wife spent most of the war in New York. After the war, even with the loss of all of his slave property and his livestock, within a couple of years he has even more money. His kids inherited huge fortunes and built their own mansions. These mansions survived until the Great Depression of the 1930s. They were on Wessyngton property but different parts of it.

After the war it turned into share cropping. Another name for slavery. At least 20 former slave families returned. Or worked as domestic servants. Many left. The black population of the county decreased by 12 to 18% after the war. Some left for Chicago and Indiana to find better opportunities.

CG We’re looking at a diorama of the site.

RD One of our curators did this based on topographical studies. When you’re standing down here (points) it’s truly like looking at a castle on a hill. The slave cabins were located on the hill. The kitchen and smoke house are still there.

CG Do the slave quarters still exist?

RD They existed until the 1980s. There is just one which has been moved. So we get at least a partial idea of their dwellings.

CG Was it through shame that the slave quarters were torn down?

RD No. It had more to do with property taxes. For every structure you had you had to pay taxes on it. When the Roberts purchased the property they let them decline.

CG Is this a typical slave cabin that we’re looking at?

RD Yeah. Our designer Mark Cooper did that with foam believe it or not. Stage craft did an awesome job and we use it to show daily life on the plantation.

CG When we visited the Hermitage we saw the slave quarters and were amazed at how many people were crammed into them. It was very dense and unhealthy.

RD They had a decent amount of space with yards. But you’re absolutely right. We had a teacher’s workshop here and they were surprised that share croppers were living in the former slave cabins all the way to the 1980s. There was a woman at the workshop and she was the daughter of the last black caretaker at Wessyngton. She was in her 80s. We were talking about the cabins and someone asked “How big were they?” The guide said “Ask Narcissus because she was born in one of them.” She said “Well. There was a kitchen. There was a room. There was a loft (for sleeping). There was a porch.” That was basically it just like you saw. (At Hermitage)

AH At Hermitage we saw a number of two family cabins.

RD It varied. Even in the model we tried to put different cabins. They weren’t all uniform. At Jefferson’s Monticello they were like row houses.

CG Going back to Nat Turner you have the family living in the mansion surrounded by some 200 people who really don’t like them. One would image a lot of paranoia.

RD That’s the thing about control. It’s punishment combined with a little bit of paying them. What we do know is that after the war the plantation owners were surprised when their former slaves left in droves. That shows that the slaves were very good at deceiving their owners. They were acting content a lot of times. As soon as the war comes they’re gone. Most of them.

Ones that came back were often the same ones that ran away. They came back, according to John Baker, because Wessyngton was wealthy and still the best employer in the county.

(“The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation: Stories of My Family’s Journey to Freedom” Simon and Schuster, 2009, 417 pages, illustrated, with bibliography, notes and index. ISBN 9 781416567417)

He thinks that economics trumped feelings. Which is why a lot of them were willing to come back and work as share croppers.

CG In the films of the past two years Twelve Years a Slave and Django Unchained we have seen the incredible brutality of the slave owners including the wife of an owner. One would imagine that this inhumanity would inflict severe psychological damage on the owners as well as their victims.

RD Exactly. I wish we knew more about that. First off they thought of it as a moral and ethical institution. Many southerners who didn’t own slaves saw the Bible as justifying it. It had been done for generations. There were passages in the New Testament. In fact we have a book on display “The Bible’s Justifications of Slavery” that was written in the 1850s. There are parables about honoring your master just as you would honor God. Of course there are lots of references to slavery in the Old Testament as well. I’m not saying that it’s not flawed logic.

CG It’s the Bible.

RD There was the feeling that if we do not elevate these people they will just run amuck. They were exploiting them. No doubt about it. But they were uplifting them and giving them a place.

CG Jefferson’s recorded remarks about the inferiority of blacks were horrendous. Horrifying when you consider that he was President of the United States.

RD You have to think that at first and second that we wish we knew more of how people thought about it. Similar to Twelve Years a Slave we know that the women of Wessyngton were involved in the management of the plantation as well as punishment. We don’t know if they enjoyed the power or sometimes thought I hate that I’m in this position. As you remark about the psychological aspect of this.

CG So women were whipped.

RD Yes.

CG Then what we saw in Twelve Years a Slave has a factual basis.

RD Yes.

CG In terms of a relative scale of the horrors of slavery how would you rate this plantation? We assume that some slave owners were more severe than others.

RD That’s really hard to do.

Mary Skinner (Museum’s publicist) That’s not what we are trying to do with this exhibition. The exhibition is based on the book by one of the slave descendants (John F. Baker, Jr.) and his research. We’re not making a universal statement here. We don’t feel like that’s our job.

CG Let me rephrase then. How would slavery on this plantation be viewed relative to others?

RD In Tennessee, according to John’s research, in terms of material items they possessed he felt like they were doing pretty well.

CG What you’re saying is that through the task system with a third of the profit of the sale of the tobacco in their own plots there was some money to buy things. So it was possible to obtain some necessities beyond what was provided.

RD That’s correct.

CG Can you describe meals? Were there three a day?

RD I’m not sure that we know that. Pork was the main thing in their diets and we know that they all had their own vegetable gardens. They grew their own greens. We have records where the families would periodically go to the smoke house and collect their rations.

AH In other words they didn’t eat meat unless it was given to them. They worked from dark to dark. So what was their breakfast to start a day of labor? Did they have lunch and when was it served?

RD A good question but I don’t know. The day varied with the season. During the summer there would have been long, long hours. I was just talking with my Mom last night. She grew tobacco in Kentucky and said it was the exact same way for her.

MS My mom grew up on a tobacco farm in Kentucky. Her brothers fought in the war (WWII) so she and her sisters had to take over the tobacco production. She talked about it being the hardest thing she ever did in her life. One time I told her I wanted to do it for some extra money and she said to me “You wouldn’t last one hour.”

RD This is the final room of the exhibition where we deal with the Civil War. We wanted to talk about how European and African American cultures merged to create the unique southern culture through music, food and story telling.

CG (Looking at a display of simple, home made stringed instruments) This is unique. Look at the homemade cello. Amazing.

RD This is a book from Wessyngton with recipes. Here’s one for ketchup. Some strange things with calf’s heads and turtles. There are not a lot of meat recipes. I think the meat they knew how to do so these are more baking things. Half of the book is food recipes and half of the book is medicinal recipes.

As I said I love that we can talk about the families after the war. There is a variety of names. Many of the families kept the names of previous owners. Even back to the 1820s a lot of them took that name. It gets really confusing. On the census records in 1870 and 1880 sometimes they used different names. In 1870 they may be Washington and in 1880 they may be Terry.

CG Is this woman (looking at a photograph) the descendant of a slave? She looks very fair skinned.

RD She is. That’s because her father, Granville, by oral tradition was the son of George A. Washington and a slave woman named Fanny. So yeah, that family was very fair skinned.

CG Thank you for taking the time to meet with us.