Thomas Jefferson's Monticello

An American Masterpiece by a Founding Father

By: Charles Giuliano - Jun 06, 2008

During a recent road trip we were able to visit two great American homes, Falling Water, by Frank Lloyd Wright, in Mill Run, Pennsylvania, and Monticello, by Thomas Jefferson, in Charlottesville, Virginia. As a "control" in this essay and exercise in superlatives we also toured the Hermitage, the home of President Andrew Jackson, near Nashville, Tennessee. We have previously written about Falling Water and the Hermitage and these essays have informed our thinking and approach to writing about Jefferson's Monticello as well as separate reports on his design for the University of Virginia and the State Capital in Richmond. Our architecture and design writer, Mark Favermann, will soon be visiting Falling Water and plans to file his own observations on the Kaufmann residence near Pittsburgh.

Prior to visiting Monticello I had toured it some 20 years ago while traveling with my Mom. Recently, I viewed with great interest the HBO series on John Adams. That prompted reading the John Adams biography by David McCullough. In his rich and absorbing study Jefferson had not been treated favorably particularly in contrast to the far less widely known and appreciated Adams. Compared to the handsome, charismatic, creative, inventive Jefferson, the dogged and plodding Adams is a harder sell. But McCullough set forth compelling arguments for a reappraisal.

It is particularly significant that Adams, a shrewd and conservative businessman and investor, left an estate of some $125,000 which adjusted for inflation is a considerable fortune that sustained the family through generations. While Jefferson left about the same amount in debt.

Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, within hours of his great friend and rival, Adams. It was 50 years to the day of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. But Jefferson's heir, Martha Jefferson Randolph was forced to sell Monticello to James T. Barclay, a local apothecary, in 1831. He sold it to Uriah P. Levy, the first Jewish American who served a full career as a commissioned officer in the U.S.Navy. The house was seized and sold by the Confederate government. Monticello was reclaimed by Uriah Levy's nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy, a New York lawyer, in 1879. The home was purchased from him by the Thomas Jefferson Foundation in 1923. The building was restored by architects including Fiske Kimball and Milton L Grigg. The Foundation manages the property which is now open to the public. Only the first floor and work spaces under the grand lawn are available to visitors.

While the home has been brought back to its original condition with period furnishings, to some extent, Monticello has been sanitized. There is little to suggest that it was an active plantation of 5,000 acres supported by the labor of 150 slaves. In the work areas under the lawn there are a couple of indications where a cook or worker resided. These are meager quarters and do not indicate the actual circumstances of the general field hands.

In his will Jefferson liberated several slaves but only individuals who had trades that would allow them to be self supporting. Because of his great debt the 150 slaves represented a considerable financial asset to settle creditors. This "liberation" of a token few of the slaves did not include Sally Hemmings his slave/companion and mother of one or more children by the master. As a gentleman of his time this was not unusual. As a Founding Father, President, and author of the Declaration of Independence, however, it is a terrible part of our history and legacy as a democracy. It is sobering to consider just how many of the Presidents prior to the Civil War were slave owners. Jackson owned some 600 slave in his lifetime. George Washington was a slave owner.

One would like to think that these Presidents and Founding Fathers were the better kind of Massahs, who arguably, did not whip their slaves on Sunday. There is, however, little actual documentary evidence on this divisive subject. Although Jefferson's own writing on the subject can be nauseating. The fact that Jefferson "owned" and exploited the children he fathered with his mistress is a particularly troubling issue. One of these "sons" was a household servant. One wonders about the thoughts of guests at Jefferson's dinner table who were served by a man who rather resembled their host.

As a contemporary or revisionist, Northern, liberal visitor to the homes of Jackson and Jefferson it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate these issues from the pure aesthetic appreciation of historic architecture. Yes, Jefferson was a remarkable and gifted man of the Enlightenment. His architecture and design were singular achievements. He may even be the best example of the Socratic ideal of the Philosopher King or Statesman. Truly, there is no other President with his originality and range of accomplishments.

However astonishing the accomplishments of Monticello there is no way of avoiding the fact that Jefferson commanded the resources to build one of America's greatest private residences precisely through the labor and exploitation of slaves. It was their sweat and labor that funded his ability to reside elegantly in Paris as an American ambassador, study languages and culture, acquire a taste for the fine wines which he cellared at Monticello, and to fill his mansion with exquisite furnishings.

Jefferson went into debt precisely through creating a magnificent estate and sparing himself of no luxury in the pursuit of personal pleasure. The pure neo classical aesthetic, based on his study of Palladio, is exquisite. The proportion of the home and the mix of the Orders is perfection. Because of its symmetry and design the home, in reproduction, appears larger and grander than its actual scale. The rooms, by contemporary standards, are actually not that imposing. Jefferson was conscious of space by removing the usual grand staircase in the entrance and making the dining area somewhat modular. The tables were set up and removed for dining. The receiving and family rooms are rather small and his own master bedroom suite is best described as cozy. He extended his fetish about saving space by creating his bed as a space divider in a thick wall between his dressing area and study.

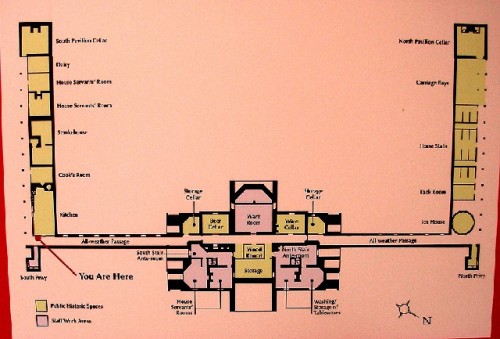

The home and its additional plantation functions are famous for their gadgets and inventions. Much is made of the clock which extends into the lower level. He used and invented devices of studying weather. To create the impression of a grand estate in the European manner he hid the work spaces of his plantation under the lawn.

Mostly, one senses from the design and architecture his notion of living well on a grand scale. We know that he was self indulgent when it came to shopping sprees or enjoying the pleasure, while in Paris, of the wives of others. He seems to have preferred, in the French manner, affairs with married women. A taste and sport he shared with Franklin while abroad. While Adams, by contrast, remained faithful and wrote home to Abigail. Jefferson was a widower who promised not to remarry. So his indulgences of the flesh were oddly vetted and justified.

Perhaps we are being overly harsh, righteous, and judgmental. Jefferson was indeed a man of his age. A man of the enlightenment. He did not create the condition of slavery. Nor is he singularly responsible for the many flaws of democracy. But that doesn't give him a free pass from the judgment of history.

So, yes, Monticello is the greatest American architectural masterpiece of its age. But, at what human cost? Ask the descendants of Sally Hemmings and others who slaved to create his vision and lifestyle.