Belinda Rathbone Part Three

Examining a Complex Legacy

By: Charles Giuliano - Feb 19, 2015

This is the third and final installment of an extensive interview with Belinda Rathbone. She is the author of the critically acclaimed book "The Boston Raphael" In its category it has been named to the New York Times Best Sellers list.

I am grateful to Belinda for her time and effort in this project. We have collaborated in editing and fact checking. The intention has been to create a fair and accurate narrative regarding her father's role during a time of significant progress and change for the Museum of Fine Arts.

Looking long and hard at his life and career, while flawed and tainted by the Raphael incident, Perry T. Rathbone clearly emerges on the short list of the MFA's greatest directors. It was a pleasure to know and work under him; then later to cover him as an arts reporter and critic. Our interactions were always lively and cordial. Perry was old school in the best sense of that designation.

Belinda's book has been thoroughly researched and balanced, succeeding in restoring her father to a rightful position in the arts of his time.

Belinda Rathbone There's a new openness to Andrew Wyeth. Just this past year there was a wonderful show at the National Gallery. Did you see it?

Charles Giuliano No, but I enjoyed the Jamie Wyeth show this year at the MFA. It was crazy enough to be interesting. The gulls were wild.

BR He certainly has his father's technical virtuosity.

CG But of all the possible contemporary artists Perry championed Andrew Wyeth. Give me a break. Does it get any more safe and conservative that that?

BR That was for an exhibition.

CG It did well.

BR The choice of that was very much based on 'what are we going to do for a blockbuster for the centennial.' (1970)

CG The public loved it. They always do. But the wild card was “The Elements” (curated by Virginia Gunter). Did you like “The Elements”?

BR It was so much fun. I loved it.

(Elements of Art: Earth, Air, Fire, Water, 1971, Virginia Gunter "Producer, " essays by Gunter and David Antin with an introduction by Perry T. Rathbone, The Artists: Rachel Bas-cohain, William Bollinger, Stan Brain, Richard Budelis, Lowry Burgess, Donald Burgy, Christo, Francois Dallegret, Geny Dignac, Edward Franklin, John Goodyear, Dan Graham, Laura Grisi, Hans Haacke, Newton Harrison, Gerald Hayes, Michael Heizer, Douglas Heubler, Peter Hutchinson, Neil Jenney, Alan Kaprow, Gyula Kosice, (Joshua Neustein, Georgette Batlle and Gerard Marx). Dennis Oppenheim, Otto Piene, Ravio Puusemp, Gary Rieveschl, Charles Ross, Richard Serra, Vera Simons, Robert Smithson, Alan Sonfist, (Christopher Sproat and Elizabeth Clark), Marvin Torffield, Uriburu.)

CG (laughing) Remember the poor eels in those plastic tubes which leaked. Did you know Virginia Gunter?

BR No, did you?

CG Yes. Pretty well. The show was ridiculed at the time but you look back at the list of who was in the show and its pretty astonishing. (Robert Smithson, Robert Morris, Otto Piene, Lowry Burgess)

BR I discuss it in the book. A lot of the artists were not known at the time but they stand up pretty well.

CG During the "Elements" press conference I asked (Perry) Rathbone "When is the MFA going to have a curator of contemporary art?" Two or three weeks later he called me at the Boston Herald Traveler to tell me that he had appointed Ken Moffett. Because of my activism he said, "I want you to be the first to know."

BR It was already in the works. He was probably glad that you asked, as it was about to happen soon.

CG We got along well given our naturally adversarial positions. The Raphael story had already broken when Clementine Brown (director of communications) called and asked if I wanted to interview Perry.

It was for a Paul Cézanne show. She made it clear that he would not take any other questions and sat in on the interview, which was not the one I wanted.

BR Clementine is a force.

CG It was a strange interview. There were a thousand questions I would have liked to ask, but we stuck to Cézanne .

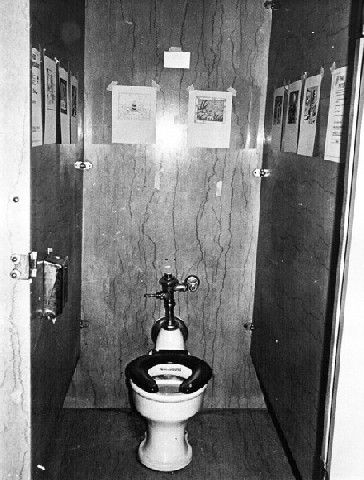

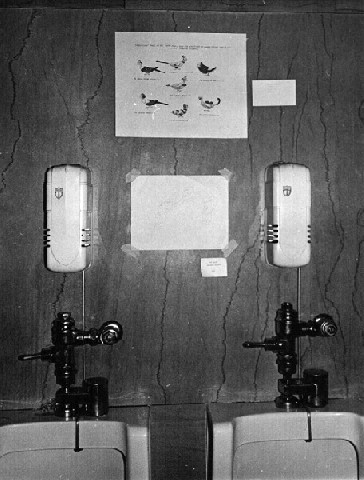

Overall, I came away from your book feeling good about Perry. You brought me down memory lane, having been an employee under Rathbone back in the day. There were so many individuals and characters I knew. Like Clara Wainwright (then Clara Mack) who worked for Hanns Swarzenski. Laura Lucky who worked in the painting department. Diggory Venn, the head of education. He's the one who stumbled upon the “Flush with the Walls” event in the men's room. It must have been fun to talk to those people.

BR It was. It really was. There were people who were very nervous about what I was doing, if I was going into the Raphael affair. For my siblings and friends, it seemed the last thing I should want to do to bring up that painful episode. Why rehash and revive it when it's something we're hoping that people will forget about? Once they realized I was going to do the whole picture they just hoped I would do a responsible job, crossed their fingers, and prayed.

CG That must have been an enormous burden of responsibility.

BR Yeah. I guess it was. In the heat of it there were times when I went to bed at night, got up in the morning, and felt as if I hadn't slept. Because I was still thinking about the Raphael. It totally took over my mind.

CG Doing this kind of work you never get a day off. This project took you two or three years. Are you going to write another book?

BR I'm thinking about a next book. But I'm not ready to talk about it. It would be a biographical art book. Like this one. That's what I do, art world related biography.

CG I think you're a wonderful writer. I'm a huge fan.

BR That's nice to hear, Charles. It really is. It's great to hash over all these issues. Especially with somebody who knows the museum so well and really cares.

CG There are a lot of very good art historians who could adequately write about what you take on. But you're a story teller. At the beginning of the book, for instance, visiting the Uffizi when the curator in white gloves brought out the painting, you put us in that room. I felt it. There was an emotional pregnancy to that moment. It was so much more than just looking at a painting. You could feel the process of that experience and what it meant to you. There was the sense of the curators who put on gloves and handle masterpieces as a part of their day-to-day work. There was something happening between them and you.

I just published an interview with a friend who is now a successful art dealer. We were both interns at the MFA at the same time. He talked about the significance of being able to handle the work. It's something that as a dealer he continues to be able to do, to handle the stuff. You conveyed that sense of interacting with the curators at the museum. That's what I responded to in reading your account of the experience. That's the feeling you bring to this story.

BR It opens the book well because the whole book is about what goes on behind the scenes. What people don't know. What goes on in the board room. What goes on in galleries and their back rooms. What goes on at home, and in the conservation lab. So it's quite fitting that the story starts in storage at the Uffizi. Did you see "The National Gallery” a movie by Fred Wiseman? It's really good.

CG My romance with the MFA started when I was at Boston Latin School. On Avenue Louis Pasteur it was just a couple of blocks away. I liked to visit after school. It was fun to just walk around. In those days there were creaky floors and guards napping in mostly empty galleries. My parents were members and I would often get to use the invitations to openings. They were drinks and buffet in the Tapestry room near the special exhibition galleries adjacent to the rotunda. Now there is a whole week of openings and special lists. Back in the day there was just one social event. Everything changed. Today it's so corporate.

When I worked there I would spend time in the galleries during my lunch break. There were great places to hang out, like the Catalan Chapel or the Temple Room in the Asian Galleries. You had to ask the guard to open it. There was a very special spiritual feeling to be in there with the ancient Buddhist sculptures.

BR You can still find places that are quiet. But today museums want to create a bustling, airport kind of feeling. That's what they think people feel more comfortable with. During my father's day he wanted excitement, but the whole idea was that you were entering a temple for contemplation. It was a sanctuary. Now that doesn't seem to be a desirable quality.

CG I vividly recall coming up the grand staircase to the special exhibition galleries for Perry's Van Gogh show. There weren't the kind of lines one encounters today. This was well before the era of the blockbusters like the 500,000 who viewed the MFA's Renoir show. I remember Perry's Modigliani show.

(The Harvard Crimson on October 5, 1985 reported that "The 97-painting retrospective exhibit of the nineteenth-century Impressionist drew record crowds in London and Paris, where it stayed for four and five months, respectively. In Paris, Renoir drew crowds averaging 8,668 visitors per day. In London, it surpassed the attendance record of the Hayward Gallery's most popular previous exhibit, "Picasso's Picassos," by more than 100,000 visitors. Boston will be the only American showing of the exhibit. Already, over 138,000 tickets have been sold. According to MFA press material, the most popular exhibit to come to the Museum to date was "Pompeii, A.D. 79," which attracted 432,000 visitors in 1978.")

BR Matisse. In their time they were all wildly successful shows.

CG But not with the numbers there are today.

BR During the centennial (1970), which was an exceptional year, the total attendance reached nearly a million. Today there's more than a million but how many years later? There's now a larger museum-going public but the demographics haven't really changed.

CG The MFA today, however, reflects the legacy of George Seybolt more than Perry Rathbone.

BR No, no, no, no. It depends what you mean by legacy. Oh, you mean that it's more of a business model.

CG If you visit the MFA today it's the MFA of George Seybolt. Malcolm Rogers has been the personification of that confluence of art and business. Malcolm didn't have much in the way of taste. Nobody ever accused him of having a good eye.

BR (laughing) I've read your words to that effect.

CG Growing up, what was discussed at the dinner table? Did your dad bring the museum home with him?

BR Definitely. He treated us as grown ups and never talked down to us. That doesn't mean I was paying attention. I had siblings and if they paid attention that got me off the hook. He did like an audience. My mother was a very good audience. So many names were familiar even if we didn't know them personally. We certainly knew the Swarzenskis, as I've made very evident in the book. He loved bringing people into our home and sharing them.

CG That whole thing with Hanns was really weird. Aspects of that partnership really raises your eyebrows. Who was playing who in that deal? What can I say? He was so much a part of the Germanic milieu of connoisseurship and diplomacy.

In the book I loved the story of him passing around a box of chocolates to his staff and then pulling up the false bottom to reveal a smuggled medieval treasure. Boy, you outed him with that one.

BR (laughing) Everything is contextual. There are people who would understand that as a totally acceptable way to behave. It's probably how he thought it was.

CG The story of such casual smuggling of treasures was a window into understanding the whole Raphael affair.

BR Exactly. That's why I tell that story. As it was told to me by Clara Wainwright.

CG Aha.

BR Of course, she told me that story with great fondness and humor. How could I not put that in?

CG It was so revealing. That was the mindset behind the Elgin Marbles in the British Museum. That's the way it was. That was the Assyrian reliefs. It was the mentality of great museums grabbing anything that was not nailed down.

Perry was in the wrong place at the wrong time when there was a policy change.

I think you're right. If it hadn't been for Seybolt and his ambition to run the museum, and if Perry had been a true Brahmin, it wouldn't have gone down that way. The Raphael incident might have ruffled a few feathers but ultimately was no big deal, The painting was never stolen, it just had vague provenance. At worst, Hanns and Perry didn't get their paperwork in order. There could have been a way to finesse it.

BR I definitely think so. That's the point of the book and the hope that people will come to understand the many gray areas here.

CG A final thought. What do you think Perry would say about your book?

BR I think he would be absolutely astounded. He would be so over the incident itself. He would be impressed with my research. And that I used what he left in his archives. He left things there clearly for somebody to find and use. Like the petition from the curators attempting to persuade him not to resign.

(They demonstrated their respect and gratitude as reported in the NY Times, January 27, 2000 obituary. "Curators at the museum paid tribute to Mr. Rathbone, who had always been most proud of his acquisitions, by organizing an exhibition of them in the unheard-of period of eight weeks. Called 'The Rathbone Years,' it showcased 170 acquisitions made during his 17-year tenure as director and included a pair of portraits by Rembrandt, a Greek youth on horseback (circa 500 B.C.), a German Gothic tapestry titled 'Wild Men and Moors' and 'La Japonaise' by Monet.")

CG That document exists?

BR It exists in his archives. At the Archives of American Art, for anyone to look at. I don't think it's in the MFA's archives. There's a whole lot of stuff there (AAA) that's not in the MFA's archives.

CG As you discuss he went on to join Christie's. That was a first move for a former museum director to go over to the dark side. Now it's not uncommon for curators to make that transition. He may have been the first to do that.

BR It was an interesting move.

Belinda Rathbone One.

Belinda Rathbone Two