Jamie Wyeth at the MFA

Good Genes

By: Charles Giuliano - Jul 22, 2014

The at times stunning but wildly uneven retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts through December 28 demonstrates that Jamie Wyeth (born July 6, 1946) has good genes.

He represents the third generation of one of America’s most famous family of artists. The dynasty was founded by the beloved illustrator of children’s books, Newell Convers “N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945). His son Andrew (1917-2009) was a meticulous realist remembered for “Christina’s World” with its every blade of grass rendered in egg tempera. There was an artist aunt Carolyn Wyeth (1882-1945).

It is a blessing and curse to be the third in line of such a legacy. That kind of inheritance may work in the financial world where assets roll over and accumulate. In the arts, however, each generation must develop its own skills and credentials. Genius and inspiration may be passed down but only through intensive effort is it realized.

As we see here, as signified by a retrospective at the prestigious MFA which will travel to Brandywine River Museum of Art, San Antonio Museum of Art and Crystal Bridges, name recognition opens doors.

Then what?

Perhaps typically for a critic I approached the exhibition with skepticism.

By the third generation an outmoded, conservative realist tradition has surely run dry.

True.

There are indeed turgid paintings in this occasionally surprisingly engaging survey. Too many works are arid and sterile to the extreme. Or just plain corny like the portrait of a dog and basket “Kleberg” which graces the cover of the catalogue. The cute pooch with a cartoonish ring around one eye seems straight out of a vintage episode of “Our Gang.”

Spare me.

While other, particularly newer works, are just full of energy, invention and brilliance of execution. I was just floored by a room of howling, squawking sea gulls. They are such crazy fun.

Then there is an astonishing period of groupie/ celebrity hanging out with Andy Warhol and The Factory from the late 1960s to mid 1970s.

The mutual attraction is easy to understand.

Andy loved to rub elbows and other body parts with the rich and famous. Jamie may have been rebelling from the constraints of family traditions. Perhaps he was running away from Brandywine, Pennsylvania and the enclave in Maine. He was testing the waters in the mainstream New York art world of which Warhol and his Factory were ground zero.

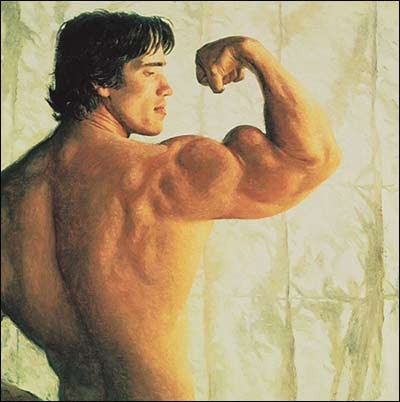

The portraits from that period of Andy, Rudolph Nureyev, and Arnold Schwarzenegger are campy but fascinating. He seems like such a square outsider swimming with the sharks.

How amusing that Warhol and Wyeth created portraits of each other. For Andy it was flash art; a quick generic Polaroid snapshot transformed into a silk screened painting. Only a handful of the hundreds of such formulaic celebrity portraits he created are beyond marginal interest. Mostly he did them for the money.

By contrast Jamie labored over the portrait as was his practice. In photos of the posing sessions, he only painted from life, we see him measuring the width of Warhol’s nostrils with calipers. His portraits were the synthesis of many sessions. During which Andy, who suffered from chronic acne, complained that Jamie was laboring over his zits.

This academic technique of measurement so annoyed Nureyev that he accused Wyeth of acting like a tailor making a suit.

The results are interesting. Wyeth’s painting of Andy is far more meaningful and nuanced than Andy’s knockoff of Jamie. There are several Warhol portraits and studies and they are intriguing. As is the suite of Nureyev portraits, including a full length nude.

While annoyed by the time and patience of posing the dancer seemed to like Jamie more than Andy. Or at least the integrity of his process. Apparently in a rage Nureyev tore up a stack of Andy’s Polaroids of him. They worked together later.

Then, untypical of his practice, Jamie used photographs to continue to work on portraits after the death of the dancer.

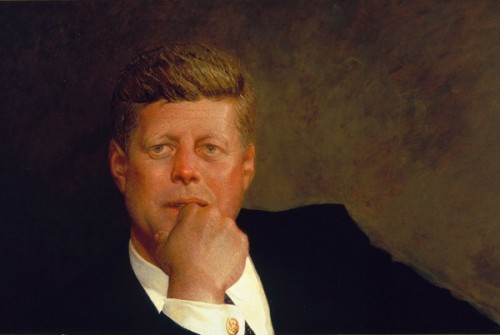

With a bit of celebrity driven hyperbole, Lincoln Kirstein (a ballet entrepreneur), a family friend declared Jamie the “finest American portrait painter since the death of John Singer Sargent.” There may be a shred of truth in that. His early JFK, a rejected commission, is a case in point. It is now owned by the MFA. His Schwarzenegger, however, is period kitsch. Before his stint in politics as a Republican member of the Kennedy clan, he is shown flexing as Mr. Universe.

A catalogue essay by David Houston “Jamie Wyeth and Recent American Realism” represents a turgid academic attempt to place him in the context of better and more interesting artists. It is more an essay on streams of contemporary realism than about Wyeth. Truth is, simply put, the artist has been a misfit, non sequitur and anachronism. This actually makes him more interesting that attempting to locate him into the art world’s zeitgeist.

The oeuvre is at its best when Jamie does his thing and is not looking over his shoulders at critics, collectors, the art world, or other artists.

As an eccentric he can be terrific.

Sure, you can see a lot of art history threading through the work.

There is the romanticism of “The Sea Watched.” It evokes the German artist Casper David Friedrich in its contemplation of turbulent nature. There is a small figure of Warhol as unlikely nature lover lurking in the lower left corner. Andy’s notion of nature was a weekend in the Hamptons. The others gazing philosophically depict his muses Winslow Homer, father, and grandfather.

The large, enervating, labored paintings of his wife driving a horse drawn carriage “Connemara” and ”Connemara Four” are related to the Eakins masterpiece “The Fairman Rogers Four in Hand.” Surely Jamie knows the painting from visits to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The family home at Chadds Ford is not far from the city.

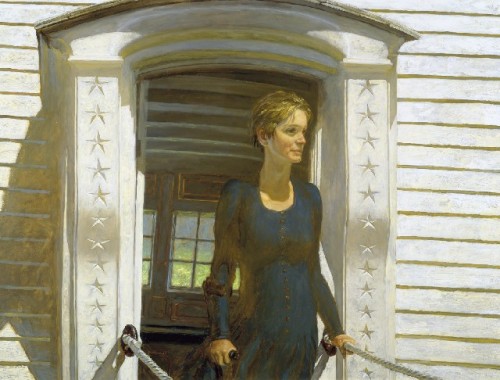

“Southern Light” depicting the artist’s wife in a doorway is particularly dead. It’s too much like an Andrew Wyeth only less so.

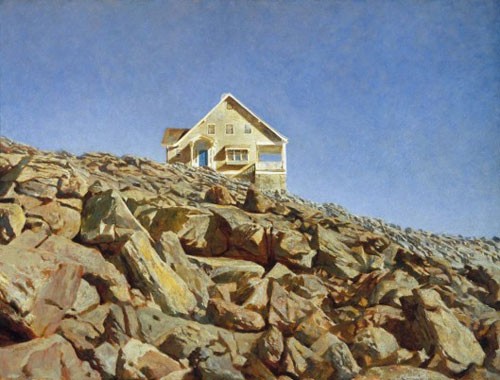

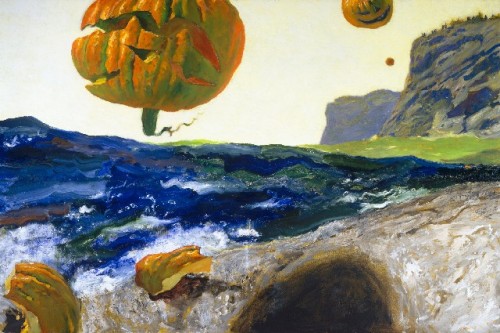

On the other hand his paintings of sheep like “The Islander” and “Portrait of Lady” are over the top fun. We just love the pumpkins cascading over the cliff in “The Headlands of Monhegan Island, Maine.” It seems to be a local post Halloween tradition to toss pumpkins into the sea. The self portrait with a pumpkin as a head is just hilarious.

There is a short video in the exhibition with the artist at work on a large painting “Inferno.” It depicts a boy burning trash on the beach with seagulls swarming about. We see Jamie working with thick watercolor used like oil paint impasto. There is a zest to that approach and he discusses working on cardboard as a forgiving support.

How wonderful that he painted a series of sea gulls depicting the “Seven Deadly Sins.”

It is utterly mad and poetic.

In such madcap works Wyeth is at his best.

Now and then this exhibition is more than just a name game.