Schnapps with Dexter Gordon

Hard Bop in Copenhagen

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 31, 2018

In 1962, tenor titan Dexter Gordon (27 February, 1923 Los Angeles- 25 April, 1990 Philadelphia) was granted a passport and escaped from the U.S.A.

After decades of a vicious cycle of addiction and incarceration, he was 39 when he performed at Ronnie Scott’s a renowned London jazz club. Initially, it was just another gig but morphed into a fresh start and new life.

He would return to L.A. to visit his ex wife and two daughters during annual six week tours. For the most part, away from the scene he got clean and somewhat straight.

The date in London was followed by a tour of England. During that time he looked for other gigs and contacted Jazzhus Montmartre in Copenhagen. He played there off and on and eventually settled, found a Danish wife, and had more kids.

In 1976, in what proved to be a comeback orchestrated by his manager and third wife, Maxine Gordon, he returned to the States and renewed a career as an ultra cool, hip, progenitor of hard bop, tenor sax.

With meticulous research, insight and loving care she has written a compelling biography, “Sophisticated Giant: The Life and Times of Dexter Gordon” (University of California Press, 2018). It has proven to be an absorbing page turner which I will review separately.

In particular, it brought me back to March, 1972 when we met for lunch including several shots of potent aquavit on a rainy Sunday in Copenhagen. That was four years before the hoopla that celebrated his return to the mainstream of jazz. He signed with a major label, Columbia, played global festivals as a headliner, and toured relentlessly. That was capped by an Oscar nominated role as the lead of the 1986 film “Round Midnight” by French director, Bertrand Travernier. In 1960, he was featured, performed and composed for the LA production of Jack Gelber’s 1959 play “The Connection.” He appeared in a short run of a later Danish production.

Compared to the racism and harassment of jazz artists, particularly those with bad habits, for generations Europe had been a refuge. Early on Paris was home to New Orleans legend Sidney Bechet. Josephine Baker and Madam Bricktop had stage and cabaret careers. Seminal tenor sax player, Coleman Hawkins, set up housekeeping in Belgium.

They were pioneers in the 1930s and 1940s. By the time that Dexter arrived on the European scene there were a lot of cats on the lam to jam with. Unfortunately, the sides cut by Bechet and Hawkins were notable for inferior European sidemen. By the 1960s that changed on two levels. There were more Americans abroad, both on tour and long term, as well as skilled European musicians.

In the mid 1950s, Stan Getz married Monica Silfverskiöld, daughter of Swedish physician and former Olympic medalist Nils Silfverskiöld. Based in Copenhagen, he often played at Jazzhus Montmartre. He returned to the States in 1961 so he and Dexter, kindred spirits, just missed each other.

On many levels Copenhagen proved to be the right fit for Gordon. There was a new generation of European musicians. Not only were they hip to the jive, as numerous recordings with a range of artists document, they were innovative artists on their own terms. The presence of so many American masters was a catalyst for this development.

Dexter’s gigs at Jazhus Montmartre lasted a month or more. The rest of the time he toured a circuit in Scandinavia, Germany and Paris. From Copenhagen he traveled by ferry and train.

That’s where Maxine entered the picture as an experienced road manager. During a train strike, early on, she navigated the band home from being stranded in Lyon.

Mostly Dexter managed to stay straight. There were notable lapses with consequences. In 1963 he cut “Our Man in Paris” one of his most memorable of several albums for Blue Note. It featured Bud Powell, piano, Pierre Michelot, bass, and drums, Kenny Clark. Hanging with them, however, resulted in arrest on charges of dealing. He got off on the plea that he was a user but there was a similar incident that got him banned from Stockholm.

This made his return to Copenhagen difficult. With the help of a physician who vouched for him Dexter eventually became a permanent resident. He learned to speak Danish as I discovered. In the slammer he taught himself enough French to read Les Miserables in the original. Maxine informs us that he was an avid reader.

My week in Copenhagen was a fluke. At the time I was a music critic for the former daily Boston Herald Traveler. A colleague from our library had taken a job with International Weekends. The company organized a weekly package to Copenhagen. If there were seats open for the Friday flight they were offered to HT journalists for $75. Many of us enjoyed that opportunity.

There was just one catch. You could be out of the office for a week but had to return with a Sunday piece. Not knowing what to expect in Copenhagen proved to be a challenge. That started with the flight itself in a small commuter plane. It entailed refueling in Gander, Newfoundland, and Reykjavik, Iceland.

From the suburban hotel there was a bus to town. On many levels Copenhagen reminded me of Boston and its Back Bay. There was a walking street that combined high end stores with porn shops. The liberal Danish approach to the sex industry was a major tourist attraction.

When our group boarded a bus for the live sex show I opted out. The concierge offered me a comped ticket to the Royal Danish Ballet. On the previous evening I had seen their Swan Lake. I was surprised by a nude production of On the Beach.

By word of mouth I found Club Montmartre. It started in 1959 with Dixieland jazz.

On New Year's Eve 1961 Jazzhus Montmartre was reopened by Herluf Kamp-Larsen. It evolved into a matrix for jazz in Europe. American artists were booked with a house rhythm section of American pianists Bud Powell and Kenny Drew, with Danish musicians Alex Riel, drums, and Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen, bass. NHOP, as he became known, was one of the most renowned musicians of his generation particularly for tours with pianists Oscar Peterson and George Shearing.

It cost about a dollar cover charge for the small, packed, smoky club. There were benches for cheap beer and pub food. On the walls were plaster masks in an ersatz African motif by Mogens Gylling. They disappeared when the club closed in 1976 but were recreated by the artist during Copenhagen Jazz Festival 2010. The club became a legendary home away from home for a generation of mainstream jazz artists.

Looking for a story I caught up with owner, chef, and waiter Kamp-Larsen. We met for dinner in one of three Chinese restaurants in Copenhagen.

“I stared with the club about ten years ago” he said. “At the time there was no place in Scandinavia to hear live jazz. I bought out the other backers one by one and now I am the sole owner. I don’t make any money on the club as taxes are very high. Income tax is 41% and there is a new artists’ tax on talent we bring in as well as a 15% sales tax. My salary comes from earnings as a waiter

“I have an apartment in the old section of Copenhagen where I pay $30 a month for rent compared to an average of $150. I have a small boat with a cabin and like to sail on nice days before opening the club for lunch. During two month holidays in Spain I can live very cheaply. Recently the jazz musicians union applied to the state to help support the club to bring in major musicians.”

Despite low income and high taxes he stated “I love Copenhagen and would never leave here. I have no desire to visit the U.S. like the jazz musicians who live and work here. Many say it’s because they don’t want to put up with the hassles of life in the States. I recall when Bud Powell lived here. For a long time he was the house pianist at Montmartre. Right now Ben Webster from the Duke Ellington band lives here. He loves Copenhagen. Tomorrow is his birthday. Unfortunately he is out of town playing this week. We just had Herbie Hancock. Also Dexter Gordon lives here and plays frequently. We have a very healthy jazz scene here.”

It was disappointing to miss Webster but I looked up Gordon in the telephone book. He answered in that resonant hipster patois “What’s up baby.” I introduced myself and asked if we could meet for lunch. He responded “solid baby” and designated a restaurant.

I had seen him perform during the 1970 Newport Jazz Festival. That year was notable for the 70th birthday celebration of Louis Armstrong. Dexter was among many alumni of his band gathered for the occasion.

With excited anticipation I was seated when long, tall, Dexter at 6’6” strode in. There was a palpable shock wave through the restaurant when he made an entrance. Settled into our table, after mutual salutations, he had the shakes and asked if he might have a taste to get straight. Foolishly, I opted not only to join him but attempt to keep pace.

Speaking be bop Danish to the formally attired waiter he returned with a bottle of frozen aquavit. It poured like syrup into shot glasses which we knocked back. The alcohol content is about 45 percent by volume. While it relaxed Dexter by the end of lunch I was completely trashed. Wandering into the street it felt like an acid trip but I managed to catch up to the group for a traditional smorgasbord dinner.

Somehow I scribbled notes that became the Herald Traveler piece that follows. After 1976 when he returned to the States I caught all of his Boston club dates.

With a peace offering of reefer that first time in the green room I said “Hey Dexter, remember me? We had lunch in Copenhagen.”

Meaning no offense he floored my by replying “No baby.” It came to be a riff. Each time I repeated the question and got the same response. With hipster humor it spoke volumes about the life and times of a truly magnificent jazz artist.

Boston Herald Traveler, June 4, 1972

“Ira Gitler wrote an article in which he called me an expatriate jazz man: said Dexter Gordon in a crowded Copenhagen café. “I don’t consider myself an expatriate. I still have my American passport. It’s a little hard to give up.”

In the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival Dexter played in the afternoon with Phil Woods. That was a rare New England appearance for Dexter who hasn’t played in Boston since 1965. This summer he will again play at Newport when the historic Billy Eckstein orchestra is reunited.

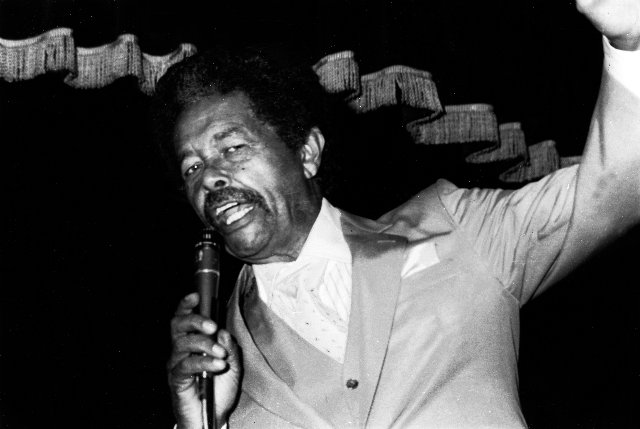

A tall imposing man with the frame of a Green Bay Packer Dexter seems to dominate any room he’s in. He has a swarthy tan tinted complexion with touches of white hair at the temples as sprightly contrast. He is a hearty mirthful man who delights in his own jokes.

It was a rainy Sunday morning in Copenhagen when I roused him out of bed. Holding his head with one bleary ear next to the phone Dexter complained about his hangover. Later at a café he introduced me to Schnapps a powerful Danish brew which hits you like a ton of bricks. But it is also good for curing hangovers.

Originally Dexter came from Los Angeles. On December 23, 1940 he joined the Lionel Hampton band while on vacation from high school. He later worked for three years with the Hampton band playing tenor sax. When the Hampton band broke up he did a six months gig with Louis Armstrong. Then booped off to the newly formed Billy Eckstein band.

His first taste of Europe came in 1962 when he gigged at Ronnie Scott’s club in London. From there he took off for a six weeks tour in England. During this time he contracted Copenhagen’s famed Club Montmartre. They had a big circuit in Scandinavia where they were still interested in jazz.

“Actually today Stockholm is pretty dull. I just came over for a casual visit and before I knew it I had been here for two years. At the time I had a hassle from getting my cabaret license. In New York I couldn’t get a card because I had a record. The original purpose of the cabaret card was to control the gangster element in night clubs. It ended up penalizing musicians who had police records and drug problems. Billie Holiday and J.J. Johnson were fighting it but it wasn’t until (Mayor) John Lindsey when they done away with it.

“I was cool when I left the States but your record follows you around. Looking back I would say that leaving the States added ten years to my life. I found that there was plenty of work for me in Denmark and the people treated me well.

“While I’ve been here I worked with people like Ornette Coleman and George Wein’s various tours. Still I’m an American citizen but I have a visa. You enter Denmark on an automatic visa of three months. To extend it I have to leave for six months and then come back. I had to do that several times but now I have a permanent residence. I just bought a house and for the first time feel like I have joined the establishment.”

By the third schnapps each we were both pretty loose. Dexter’s forehead was slightly beaded with sweat.

“What intrigued me about Denmark was that I didn’t have to look over my shoulder to see who was behind me. In the States I was getting paranoid. If you’re an artist here you get some kind of recognition. Of course here everything is highly taxed. So it’s a commitment to stay here. I still do an annual tour of the States usually for about six weeks. But my time is limited there. This year I will be there in early June and I’ll be around through the Newport Jazz Festival.”

Recently Dexter resigned with Prestige Records a contract for two albums. He also has albums on GPS, a German label, as well as albums on Dutch, Norwegian and Blue Note Records.

“I’m really excited about the Billy Eckstein reunion which is planned for this summer’s jazz festival. Eckstein had been doing vocals with the Earl Hines band. In 1943 he left Hines and took half the band with him. Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker were the heart of the band which also included me, Gene Ammons and Sonny Stitt, Art Blakey and Sarah Vaughan. Billy was a trumpeter and trombone player as well as singer so he was pretty hip instrumentally. The band was really wailing. It was the first bop band. We weren’t just playing whole notes. Plus we had some really great writers like Jerry Valentine and Tadd Dameron. This summer John Jackson will play Bird’s book. Being in that band with Bird n Diz was like college for me. They really influenced my playing. Also at the festival I’ll be playing in one of the jam sessions.”

By now Dexter finished his steak with béarnaise sauce as well as the schnapps. Letting out a hearty laugh and hoisting his glass he said “This is the devil.” With that final toast I staggered out to a rainy Sunday in Copenhagen.