A Study in Contrast Two Museums in Lisbon

National Tile Museum and MAAT Bookend Art and Culture

By: Mark Favermann - Dec 30, 2017

On a recent trip to Lisbon, two museums I visited bookended the history of Portugal and contemporary cutting-edge art and technology—The Museu Nacional do Azulejo (The National Tile Museum) and The Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT). These institutions visually and physically reflected the breath of Portuguese art and culture, one embracing the nooks and crannies of history while the other exhibited a vibrant openness to contemporary urbanity.

Located in the ancient Convent of Madre de Deus (Mother of God) and founded in 1509 by Queen D. Leonor (1458-1525), the Museu Nacional do Azulejo showcases a distinctive collection that epitomizes the Portuguese aesthetic. This eye-filling gathering underscores one of the most notable aspects of Lisbon’s alluring architecture: Its compelling ceramic tiles.

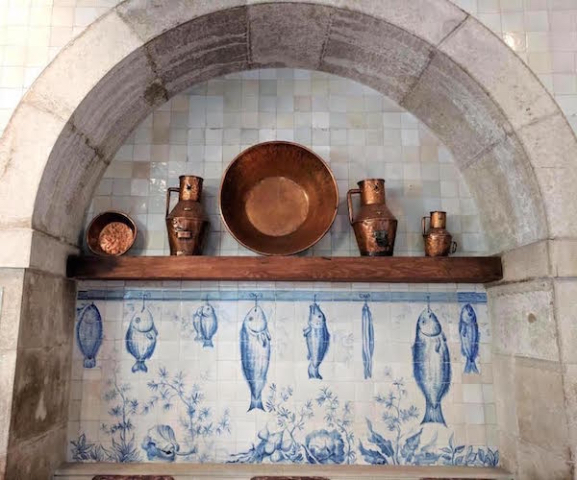

Azulejo (the Arabic al zellige) is a form of Spanish and Portuguese painted, tin-glazed, ceramic tilework. Traditionally found on the exterior and interior (walls, ceilings and/or floors) of churches, palaces, ordinary homes, schools, and plazas, azulejos were not only decorative but served narrative purposes. Today, azulejos still constitute a major aspect of Portguese architecture. They can be seen decorating restaurants, bars, contemporary office buildings, railway stations, and subway platforms. Interestingly, azulejos not only supplied ornamentation, but had a specific functional use, assisting with temperature control in homes.

Over the past 700 years, tiles have been the décor element of choice for Portugal and its former colonies. In contrast to other empires, tiles replaced tapestries, frescos, paintings, and even statuary: They are both flexible and inexpensive. Complicated installations (which were often large scale) tell stories from history, the Bible, and myth.

The earliest (13th Century) tiles show unmistakable Arab influences, such as interlocking curvilinear, geometric, or floral motifs. These were panels of tile mosaics glazed into a single color and then cut into geometric shapes. They were formally introduced to Portugal by Spain via King Manuel I in 1503. Almost immediately, tiles were applied on walls and used for paving floors. The Portuguese adopted the Moorish tradition of horror vacui (‘fear of empty spaces’) and often covered their walls with azulejos.

The mission of the Museu Nacional do Azulejo is the preservation, presentation, and study of its tile collections in its ancient (and renovated) building.The museum accomplishes this task by way of its interesting lay-out, which educates the viewer while providing a quality visual experience. Not only is the “what” and “when” of the tile’s mystique exhibited wonderfully, but the “how” it was done is clearly explained.

Because it is a former monastery, the ground floor’s chapels provide the perfect context in which to appreciate the extensive and beautiful examples of ecclesiastical tile on display. Other rooms exhibit tiles from different historical periods. The first and second floors contain marvelous examples of more contemporary tiles, including the work of 20th and 21st century artists.

While the National Tile Museum focuses more on a Portuguese aesthetic from the past, the MAAT purveys a much more contemporary and universal worldview. The MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, opened its doors to the public in October 2016. But the completed building wasn’t ready to receive visitors until March 2017. The MAAT was set up as a venue to host national and international exhibitions featuring cutting-edge contemporary artists, architects, and thinkers. The admirable mission of MAAT is to serve as a space for debate, critical thinking, and international dialogue. It offers an intense and diverse program that aims to please all audiences and ages.

The MAAT also underscores the government’s intent to revitalize the riverfront in Belém’s historic district. The museum’s newest structure was designed by the Sterling Award-winning British firm of Amanda Levete Architects. The overall project involves over 10,000 square feet of exhibitive space plus 21 thousand square feet of public space. The new building, set on a rise on the riverfront, includes a pedestrian roof that offers a spectacular view of Lisbon and the Tagus River. The structure immediately became an iconic Lisbon location.

The new building, with its memorable flowing lines design, coexists with the equally iconic Tejo Power Station. A landscape project designed by Lebanese architect Vladimir Djurovic connects both buildings.

The new building’s interior contains the Oval Gallery, a sunken oval-shaped pit surrounded by a ramped walkway. In keeping with the surrounding architecture, the MAAT’s four galleries are all sunken below ground level to keep the height of the building low. The building’s purpose is to serve and support the work of Portuguese artists and curators — while also offering them a way to connect with the international art and design communities. Implicit is the very contemporary notion of focus on the broken line between them.

As mentioned, the MAAT also occupies the recently renovated Central Tejo power station (initially constructed in 1909 but replaced in 1941) next door. The red brick former thermoelectric plant formally closed its doors in 1975, but it has now been converted into gallery space. The power station’s courtyard is also being used as one of the exhibition sites. The old power station, with its massive furnaces, boilers, and electrical generating equipment now hosts audio, visual, and interactive presentations of design, digital art, and film. This is a space in which Steampunk meets Buzz Lightyear.

In contrast, the new building boasts an undulating form that connects its grand rooftop terrace with a waterside promenade. Inspired by the rippling waves of the nearby water, the new structure is covered in 15,000 white, three-dimensional ceramic tiles. At different times of the day the building reflects different colors.

The exhibitions in the old Power Station offered a mix of topics: electronic history, product design, and art — along with an overview of the history of video presentations. The new building generally housed video works and documentaries. Overall, the buildings were more visually and experientially exciting then the exhibits they contained. It was a matter of structure overwhelming content.

This article was previously published in Arts Fuse and is republished by their permission.