Abstract Artist Ellsworth Kelly at 92

Graduate of Boston's Museum School

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 28, 2015

The abstract artist Ellsworth Kelly who died on Sunday, December 27 at his home in Spencertown, N.Y. was 92.

A graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts he maintained close ties with Boston.

There is a series of his shaped, monochromatic paintings in the John Joseph Moakley United States Courthouse which is located on the waterfront within walking distance of the Institute of Contemporary Art.

His signature work in painting, graphics and sculpture are widely regarded for its intellectual, conceptual rigor and originality. With constant experimentation, within a well defined range of abstraction, he was an uneasy fit in the dominant isms of the 1960s.

From Boston to Paris and back to New York he absorbed many insights from European and American modernism particularly as distilled through the School of Paris from Picasso and Matisse to Brancusi.

This conflated into a readily identified and resonant hybrid style. Breaking away from the Boston Expressionism of his Museum School years, he absorbed and then evolved from modernism. He was a part of the generation seeking new directions after the global dominance of Abstract Expressionism after WWII.

While in Paris he read an Art News review of an exhibition by Ad Reinhardt. He later stated that it encouraged him that America might find an interest in his similarly reductive abstract art. He later became a stable mate of Reinhardt in the understated but broadly influential Betty Parson's Gallery. Initially, she also represented Jackson Pollock.

In 1956 Kelly had his first NY solo at the Parsons Gallery. That led to being shown at the Whitney Museum the following year.

In 1959 Dorothy C. Miller, a Museum of Modern Art curator, included his work in “Sixteen Americans.” In addition to Kelly that landmark exhibition also launched the Pop Artists Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, the abstract painter Jack Youngerman, as well as Frank Stella, assemblage sculptor, Louise Nevelson, and the eccentric San Francisco based artist Jay De Feo.

In 1965 he joined Sidney Janis Gallery. The following year he was selected for the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale. In 1968 he was shown in Documenta IV in Kassel, Germany. He was included in three more Venice Bienniales and in the 1977 and 1992 editions of Documenta.

In 1973 he had his first American retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art then, in 1996, at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. That exhibition traveled to Los Angeles, London and Munich. His first major European retrospective was at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam in 1979.

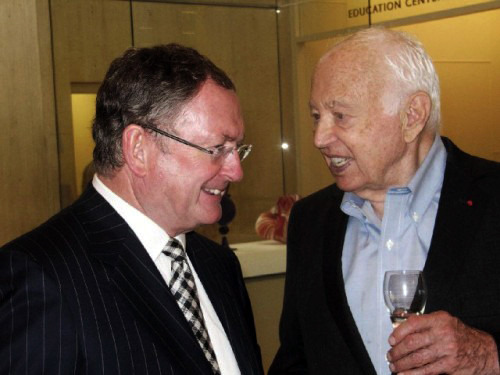

During the 2013 opening of the MFA's Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art Edward Saywell, chair of the Wing, discussed the first special exhibition in the newly renovated space.

“Ellsworth Kelly has created a total of 30 wood sculptures, the first in 1958, and the most recent one in 1996” he told the media. “Of these 19 are on view.”

Kelly attended Pratt Institute in Brooklyn from 1941 to 1942. On New Year’s Day of 1943 he was inducted into the Army serving through the end of the war in Europe. On the GI Bill he returned to the US and completed his study graduating from the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in 1948. He returned to Paris where he continued on the GI Bill for the next six years while rarely attending classes.

The MFA acquired a major work “Blue Green Yellow Orange Red” from 1968.

During the opening at the MFA he told the media “I am nourished by the past, I am questioning the present, and I am stepping into the future.”

At the Museum School he studied with the German born artist Karl Zerbe who with Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine was a leader of the movement of Boston Expressionism. The training included study of ancient materials and techniques including egg tempera and encaustic painting. There was an emphasis on figurative drawing and painting.

These roots remained as a foundation for his work. In addition to abstract painting Kelly produced exquisite line drawings based on observations from nature.

After being introduced by then MFA director, Malcolm Rogers we learned how Kelly ended up in Boston.

“I was on a boat coming home (from Paris after the war) and somebody gave me a copy of Esquire magazine” he said. “There was an article on Karl Zebre. So when I landed in New York I came to Boston and met Barbara Swan (wife of Alan Fink of Alpha Gallery.) She said ‘You’re going to stay here.’ We painted in the attic here (in the museum) and the first painting I made was one of the best I ever did because I was free and hadn’t yet found out how bad I was. Karl Zerbe was a great teacher and a perfect drawing teacher. He taught me how to see. He said 'You don’t know how to see.' "

During the press conference I asked Kelly about Zerbe. It was fascinating that he attempted to make expressionist paintings. “I tried very hard. I did quite a few paintings like that.”

Kelly elaborated on what Zerbe had taught him about drawing and how that is key to his work. Looking down the length of the I.M. Pei designed Linde Wing he pointed out the window shape at the end of the barrel vaulted ceiling over the atrium. It is the kind of form that interests him and appears in the work. “So you are not an abstract artist” I commented to him rhetorically.

"I think abstract is just the opposite of naturalism or figurative” he replied. “I can't stand figurative work. It's been done."

Kelly recalled “When I was drawing Zerbe would come up and say ‘You’re not getting it.’ And he would make three lines. I feel drawing is the foundation of all my work. I draw constantly. Not so much now.”

Rogers asked him “Did you study in the museum when you were here?”

“Yes and it was wonderful” Kelly answered. “During lunch hour to come down (from the MFA’s attic) and looked at Renoir. There is a beautiful one of a couple dancing and cigarette butts on the floor. (Ground actually as the couple are dancing at an outdoor café.) I love that painting. (“Le Bal a Bougival”) It’s one of the best Renoirs. I also painted a copy of a Tintoretto. A head about this big (shows scale with hands). That was for a class in design. I also did a copy of a gold leaf painting by (Ambrogio) Lorenzetti. I spent a whole summer doing that "Mother and Child" a shaped painting with a triangle on top.

“Later on, it started in Paris, I did two paintings in red and orange that were started together. With some other colors. And another one which was white and black. I did a book in 1951 Line from Color for which I tried to get a Guggenheim. I didn’t get the Guggenheim. But I showed the book to Hans Arp. He went through the book. It’s 40 pages. MoMA now has all the collages. He stopped at the "Orange" and said ‘This is just two colors.’ I couldn’t say anything."

But he returned to that thought at a later time.

”I was with Diane Waldman, the curator of my exhibition at the Guggenheim (1996). We were in the National Gallery in London in a room full of orange and pink paintings by Lorenzetti and I said to her ‘That’s where I got it.’ Without knowing it I did those two colors. The painting with the gold leaf. I gave it to my mother and I don’t know where it is now.”

The beginnings of the work that Kelly is today know for started in France. It was time to come home and launch a career as an artist.

“I heard about Black Mountain College” he said. “But I had spent six years in Paris and was so out of touch with what was going on in America. I got on an airplane and landed in New York. I was headed to Black Mountain College. My life would have changed if I went there. I knew John Cage in Paris. He had written ‘Come back to America. There are some interesting artists including Rauschenberg.’ "

Kelly never got to Black Mountain College after visiting with Rauschenberg. “He was the first person I went to see and he was doing all these "Combines." It was hot in August and he was in shorts covered with red paint. He said let’s get you a studio.”

The oldest of his 30 wood sculptures was made in 1958. They represent a paradox. His work is known for high chroma monochromes with distinctive geometric shapes. The wood presents an enigma. Is there an absence of color or is the artist interested in the inherent color of the wood itself? In that sense are they sculptures or, in the case of the wall mounted works, a variant on monochrome paintings?

He stated “I try to do as little as possible to the wood... I don't like circles because I feel circles are too finished. You can't do anything with it. But a square you can do something with. Curves are fabulous.”

Adding that "Shadows are very important. Shadows are always contemporary, modern, abstract... The marks in the wood grain are at least 100 years old, but the curves are today.”

As well as tomorrow comprising the legacy of one of the most renowned American artists of his generation.