Aguascalientes

Colonial Jewel of North-Central Mexico

By: Zeren Earls - Dec 25, 2014

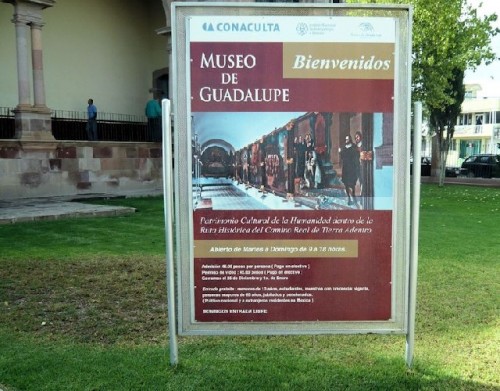

Leaving Zacatecas early in the morning, we headed south for the last leg of our itinerary to Aguascalientes; the capital city of one million of the eponymous state, one of Mexico’s smallest. On the way we stopped in Guadalupe to see its beautiful cathedral and museum. The museum is known for its revered colonial art collection, which is housed in a former school for missionaries, founded in 1707 by Franciscans in what was then northern New Spain.

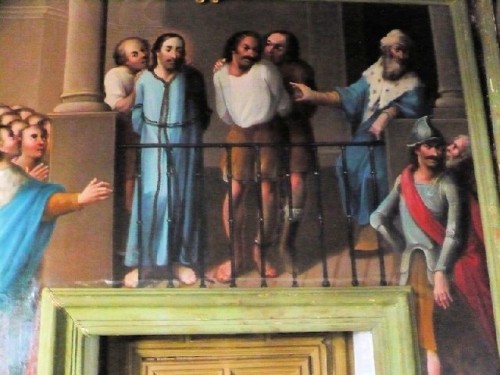

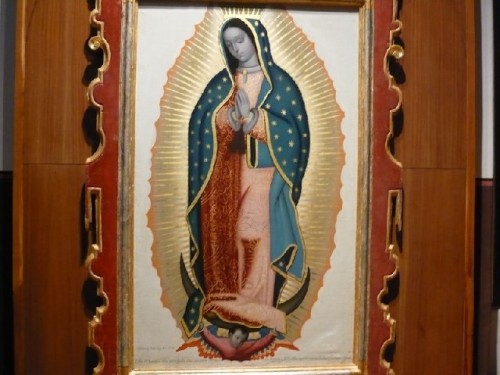

Designated by UNESCO in 2010 as a significant part of the Historic Royal Inland Road and a World Cultural Heritage site, the Guadalupe Museum holds some 800 pieces of religious art, collected from this and all former monasteries in the state. There are murals and oil-on-canvas paintings, some of which wrap around the arches and doorways of the building’s 27 rooms. Works range from portraits of Franciscan friars and miracles by Saint Francis of Assisi to paintings expressly made for the cloister and hanging in their original spots. Passing through a Baroque arch, one encounters portraits of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Wall texts with diagrams pointing to various parts of the paintings explain their symbolic meaning: for example, brocade dress for nobility or a book in hand for Christianity. The upper cloister contains oils recounting the Passion of Christ, recalling the sequence of events from Christ’s trial to the 14 Stations of the Cross.

Following a short stroll in Guadalupe, we headed to Loreto, a small town in the state of Zacatecas known for folk arts, such as basket-making, leather and metal works, masks, and pyrotechnics for festivals, in addition to sweets. Neither driving nor walking around led us to any such shops. When we inquired about basket-makers, we were told that this was a dying craft, as masters leaving for work opportunities in the US have not been returning.

Saddened by this news, we continued to Aguascalientes, arriving at the Hotel Francis at what we thought was around dinnertime. Feeling tired and hungry, we wanted to call it an early day. Unfortunately, we could not find a restaurant willing to serve dinner before 8 pm. This reminded me of my first visit to Spain; when a friend and I had arrived at a restaurant in Madrid for fine dining at 6 pm, we had found the kitchen crew out front peeling potatoes! In Aguascalientes we were fortunate to locate a café where we could get crepes and sandwiches in advance of Mexican dinnertime.

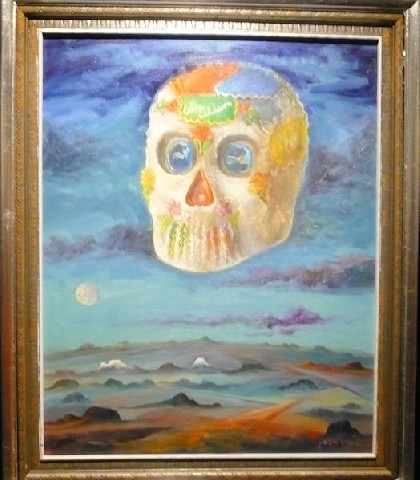

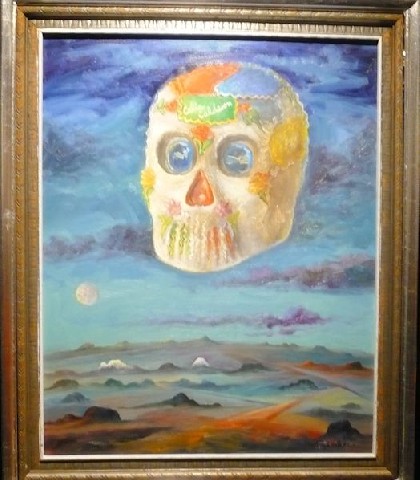

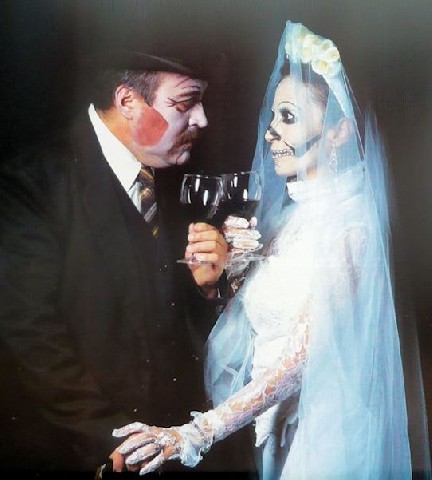

After touring the city by car in the morning, we visited the National Museum of Death, featuring a fantastic collection of 2000 objects, dedicated to dissemination of objects related to the theme of death. Artistic representations, mostly from Mesoamerica, were grouped as pre-Hispanic, sacred, craft and contemporary art. Gallery displays included skulls, masks, Catrina skeleton dolls, banquet tableaus, paintings, and works by children, ceremonial pieces, ceramic urns, and other funerary objects. The displays also included some works from other cultures, such as Egyptian burial objects, funerary caskets from India, and small replicas of the terra cotta soldiers of Xi’an, China. The death theme continued to the patio and cafe of the museum, with skeletal mannequins as brides amidst the outdoor furniture. At the museum shop I purchased a ceramic Catrina doll adorned with flowers.

The nearby Contemporary Art Museum was our next stop. The works currently exhibited here responded to human, social, and political concerns. A photography and text installation by Ivan Buenades — a series of small sgraffiti in decorative frames covered in black and surrounded by slingshots — appeared like remains rescued from a fire, as if someone had painted a future that had finally arrived, symbolizing a world with depleted natural resources.

An installation of “incinerated” objects by Máximo González pointed to a ruined urban landscape, symbolizing what mankind has done to the earth, ultimately burning down its own house and leaving only a starry night in the end. Nearby a house constructed out of a corrugated cardboard sheet suggested a new start and the return to a simpler life. A joint installation by the two artists, using recycled plates, invited the viewer to gather around food — a basic need — and discuss all that has happened.

During a well-deserved lunch break, we went to an authentic Yucatan restaurant, with waitresses in native dress and a ceiling covered with baskets serving as lampshades. Following a delicious meal of tamales wrapped in corn husk, we headed out to two more museums, crossing pretty squares and stopping by street vendors along the way. Strands of beads framing one of the carts caught my attention, along with a beaded belt the native vendor was wearing. I was charmed by the belt and felt lucky that she let me buy it along with a thick strand of coral beads.

The José Guadalupe Posada Museum is housed in what was the priest’s cloisters and residence, next to the 18th-century baroque church of El Señor del Encino (Our Lord of the Oak) in a charming neighborhood. The museum is named after the graphic artist, who is a native of the city. He lived in the late 19th to the early 20th century and is considered to be the founder of modern Mexican art, with a profound influence on Rivera, Orozco, Siqueiros, and Kahlo. The original signed printed plates with which he created his graphic images are displayed in the museum.

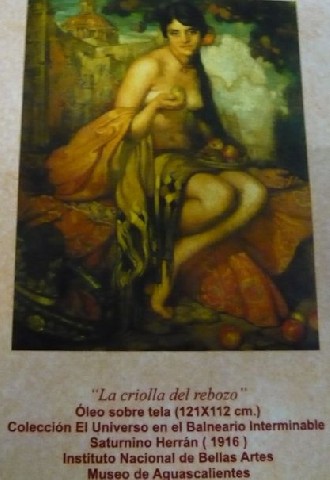

The Museum of Aguascalientes is in a handsome neoclassical building with lovely little gardens, patios, and fountains. The exhibits feature works by Mexican painters and sculptors, including Leonora Carrington, the British artist, who spent most of her life in Mexico. A large stained- glass piece faces the courtyard, which has massive carved stone and bronze sculptures.

Waiting till 8 pm for dinner allowed us to see a lit view of the city at dusk. The colors of the Mexican flag — green, red, and white — appeared on buildings in lights, which also enhanced the majestic appearance of the cathedral, accentuating its baroque façade and towers. Saturnina, named after Mexico’s famed painter and native son, Saturnino Herran, one of whose works was featured on the wall, was the restaurant of choice for dinner; also my farewell to the group, as I parted from them the next morning to go to Guadalajara for my return trip to Boston.

On their way back to Zacatecas to begin the long journey to Seattle, my friends dropped me off at the bus terminal in Aguascalientes. At the end of a two-and-a-half-hour bus trip and a prepaid cab ride, I arrived at the Hotel Tapida, a five-star resort hotel on top of a hill near Guadalajara airport. The bellboy who helped me to my room piqued my curiosity with his flawless English. In response to my question as to the source of his language acquisition, he said that he worked as a mechanic in a garage in Los Angeles and that he had been hired at the hotel while visiting relatives at home.

As soon as I settled in my room, I went exploring the surroundings of the compound. Flowering trees lined the pathways connecting the rooms; an expansive, free-form swimming pool beckoned nearby; and the city below against the backdrop of mountains stretched as far as the eye could see. After checking out the various places to eat, I settled on the café, as it was only 6 pm and too early for fine dining. Even there I was the only customer. I ordered seafood salad with oil-and-vinegar dressing, which arrived in separate bowls to be spooned over the salad. Somewhat amused at the large size of the bowls, I smiled and thanked the waiter in Spanish, as his English was non-existent.

At 6 am the English-speaking bellboy knocked on my door, dressed as my private driver to the airport courtesy of the hotel, making it clear that knowing English not only opened doors to jobs, but also elevated one’s rank. Working-class people who speak good English are a rarity outside of heavily visited tourist spots in Mexico. Among the people I met who had learned English by going to the US, one had worked as a construction worker in Maryland, and another as a farmhand in Kansas. They are back in Mexico and, thanks to their English, have been able to improve the lot dealt to them as young people.

Although this was my sixth trip to Mexico, I enjoyed yet another opportunity to explore regions with natural beauty, cultural insights, and wonderful people.