Picasso Black and White

Chiaroscuro Theme at the Guggenheim to January 23

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 17, 2012

Negotiating the Guggenheim Museum we prefer to spiral from the top down. It is the more natural flow of gravity to descend through the exhibitions. This has the aspect of viewing the works other than as intended by curators.

It is the equivalent of starting at the end of a book, its conclusion. Then, already knowing how the plot has played out, working through to the beginning.

In the case of Picasso Black and White there was the collateral damage of starting with the worst, late works, pretty awful by the way, then progressing to the generally superior earlier works.

The impact is like Dante’s Divine Comedy, where, accompanied by the shade of Virgil, he started with Hell, progressed through Purgatory, then made it on his own to Paradise. There to be united with his deceased muse Beatrice.

In the instance of Pablo Picasso, however, there were far more than a single muse; actually many women who inspired periods and specific works.

One of whom was Francoise Gilot, the mother of his children and a mediocre painter in his manner. She got her revenge by writing a scathing but absorbing book Life with Picasso. Then was the source for Arianna Huffington’s miserable, feminist screed Picasso Creator and Destroyer. It became the inspiration for one of the worst movies by Anthony Hopkins.

As a Spaniard throbbing with duende, arrogance, testosterone and genius Picasso readily lends himself to caricature.

An artist friend told me that his wife refuses to look at works by Picasso because of his reputation as an abuser and womanizer. She would indeed find solace in the books by Gilot and Huffington that tattle on the man, rich in details of the boudoir, but are generally inept in dealing with the work. For that, we have the progressive volumes of John Richardson who knew him as a neighbor and friend.

But the Gilot book offered a vignette that provides insights to the dilemma that we face while careening around the loops of the Frank Lloyd Wright building.

It was the daily task of Gilot and whoever was at hand to coax him out of bed. To get him motivated, up and running, to trot off to the studio and make Picassos. This exhibition provides abundant evidence of the result.

Much of the mid to late work was essentially a sustained parody.

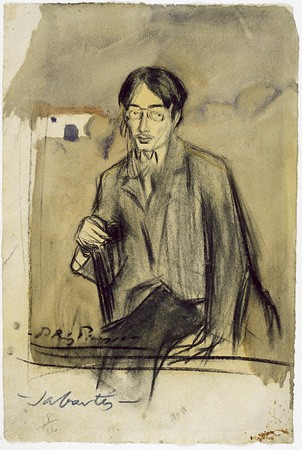

Picasso making Picassos; which, because of the signature, based on the earlier reputation of the artist, had enormous market value. It sustained him through the lifestyle of royalty. Vast wealth empowered him to abuse those around him- family, friends, dealers, critics, collectors- who came to pay homage. Off and on his poet friend from Barcelona, Sabartes, served as secretary and gate keeper. When he hadn’t fired or neglected him for some alleged slight or embezzlement.

Rather than pay cash Picasso, typically, gave him works, many from the vital early periods. Upon his death Sabartes left them to the city of Barcelona. They are the spine of its great Picasso Museum.

The dismantling of the monument of Picasso began in 1965, before the artist’s death in 1973, with The Success and Failure of Picasso by the Marxist critic John Berger. It is a dense and complex study that describes how the expatriate Spaniard became ever more isolated from friends and aesthetic sources. At the end of his life Picasso lived in an isolated villa with a social moat surrounding him. The final gatekeeper and majordomo proved to be his wife Jacqueline. She served the multiple roles of lover/ muse/ nurse/ widow.

Those that got through came by invitation only. That also extends to fresh ideas and inspiration. The artist was gorging on his own aesthetic flesh resulting in an art of gout. We see abundant evidence of this necrophilia at the Guggenheim.

Significantly, there are many pastiches but few great works in this exhibition.

We first stumbled upon one, almost by accident, The Woman in White, loaned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It was poorly placed on a narrow wall next to an entrance to a gallery off the spiral. Given its importance why was it not more properly installed as the centerpiece of a niche?

As part of the research for the 1997 MoMA exhibition Picasso and Portraiture: Representation and Transformation William Rubin identified the enigmatic, sensual, classical woman as Sara the wife of the rich, American, artist/ dilettante, Gerald Murphy. The jury is still out as to whether his advances on Mrs. Murphy were successful. But as one of the great beauties of her era, as evidenced in this singular masterpiece, there is little doubt that he coveted her. It was usual for Picasso to seduce the wives and lovers of his friends.

There are just three other great works in this Guggenheim exhibition; two line drawings on canvas of his wife Olga which I had never previously seen, and, from the Blue Period, the riveting Laundress.

The thesis and inspiration for an exhibition devoted to the grisaille Picasso is compelling and apt. It has just not been executed with the level of works fully to prove its intent.

There is a convincing argument that Picasso was never a master of color. For that we have the current Metropolitan Museum exhibition of his greatest rival, Henri Matisse.

The art of Picasso is rooted in the parched, arid colors of Spain. It is the black and white, the chiaroscuro of Goya, signified by his monumental series of Black Paintings in the Prado. The color of Picasso and Goya is red. The blood of bullfights and massacres.

Interestingly there is no color, not a splash of red, in his masterpiece Guernica. How different if that great work returned to New York for this special occasion. Image this project constructed around that centerpiece.

It is also confounding that the curators have not shown us the Picasso of Analytical Cubism (which followed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907). For that breakthrough period which changed 20th century pictorial space, they drained their canvases of color, working in black and white and earth tones, to focus on the fracturing of space and forms.

Only gradually, once they had completed the initial phase of intensive research, did color return in such seminal works of Synthetic Cubism as Picasso’s Musicians from 1921. But it is hard, flat, strident color, unlike the joyous celebrations of Matisse.

With a fixation on value rather than hue Picasso was a phenomenal graphic artist. That might have been a rich and insightful sidebar to this exhibition which primarily focuses on paintings. Although many of the works on display are really drawings. He was rich and successful enough to treat canvas as though it were paper.

Which is a puzzle of this exhibition. It is left to the viewer to decide when Picasso used black and white as a discipline, challenge, and aesthetic decision? And when he was just knocking off something which he was too lazy to paint in color?

Ultimately, this overblown, flawed project has the uncanny result of revealing that Picasso, the greatest monument and genius of 20th century, had feet of clay.

Once he was undone by fame and adulation there were too many days when he got out of bed, had lunch, and went into the studio to make Picassos.