Iestyn Davies Delights at Carnegie

Foremost Among Countertenors Following David Daniels

By: Susan Hall - Dec 17, 2011

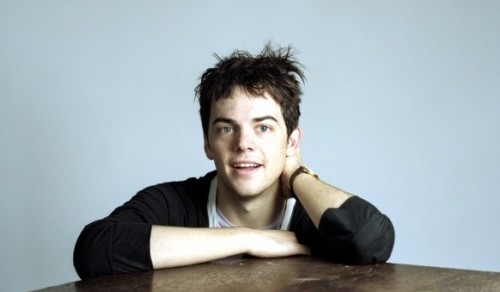

Iestyn Davies, Countertenor

Kevin Murphy, Piano

Weill Recital Hall

Carnegie Hall

Iestyn Davies is an accidental countertenor, but this is the last thought you might have when you listen to him. As a teen, he was more engaged with pop than classical, but when he opened his mouth to try the falsetto and his neighbor in the Well Cathedral choir told him it sounded good, Davies started to study the countertenor. It didn’t hurt that pop stars like Eddie Kendricks of the Temptations and Michael Jackson chose this same unique register. Davies seems a natural, whose experiment with the falsetto has grown into a major performing career.

In the early days, castratis' vocal training included both imitating birds and competing with trumpets. Davies has not been put to these tests, but you can hear the lovely lyricism of a bird’s call and the bite of the piercing trumpet in his delivery.

The program began with Purcell, to Davies “a heady mix of elation and melancholy.” In his musical take, Purcell is a delight to hear. We are carried back in time and mood but still held very much in the present by Davies’ deep expressiveness. The interface with Kevin Murphy at the piano worked well. This evening would bathe us a wrenching sadness, spirited recovery and the simple joy of music.

We got on to Davies in his first performances in New York when the prescient George Steel cast him as Arsace in Handel’s Partenope at the New York City Opera. Turns out we were not alone. Young composing phenom Nico Muhly liked the voice so much that he saw Partenope three times.

Davies sang the world premier four of Muhly’s Traditional Songs, commissioned by Carnegie Hall. In folk music, words and text are on equal footing. Muhly composes with mystery and even, in the case of The Bitter Withy, irreverence, in a take on the Christ child who sounds a bit like a badder George Washington as he is reprimanded by Mary for drowning three boys. How fortunate that Muhly gives us the leaping range of the Davies voice, his immaculate understanding of text, and also an opportunity for the Murphy to provide what Muhly calls a "highly stylized but understated accompaniment."

Davies loves to sing Handel, and the composer rewards him in turn. Sento amor con novi dardi, the Scene 5 aria from Act I of Partenope is the revelation it describes. Although the next aria from the opera had all the ferocity of the rejected lover’s pain, Davies vocal decorations transported.

Interestingly, Davies reports being less comfortable in the realm of German lieder which he now entered. Yet he appeared at ease on stage, stepping forward and back, propping himself on the piano, and forming a triangle with his fingers, as though to capture both sound and feelings in a special space.

A song of Peter Warlock’s, apparently composed on Christmas Eve, while drinking on the town, Bethlehem Down won a Christmas carol contest for this friend of D.H. Lawrence’s, who gave up on Lawrence after the author depicted him in an unflattering light. This raunchy aspect of Warlock did not emerge as Davies sang this affecting tune, purged of context.

In delightful written responses to an interviewer, I note his current at-home listening is focused on Handel and Herbert Howells, whose nostalgic song, O My Deir Hert, he performed with particular sweetness.

Britten, who advanced the modern countertenor’s cause in the role of Oberon in his opera Midsummer Night’s Dream, ended the formal program. Pure tone, firm pitch and clean projection characterized Davies performance throughout. He is innately musical, and casts a line with perfectly expressed dynamics, from low to high, and soft to piercing.

His sense of humor, clearly apparent in roles like Arsace, was on display in encores where he quoted his favorite limeric which ends the Britten Oliver Cromwell song: “If you want any more, you can sing it yourself.” Who would dare comparison with this brilliant young talent.