At Mass MoCA, The Rape of Europa: a Neverending Story of Art Looting

Crimes of greed, pride, falsehood, and hypocrisy in the art world

By: Michael Miller - Dec 17, 2006

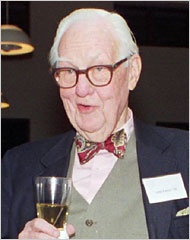

Mass MoCA presented "The Rape of Europa" last Thursday as part of a documentary series called 'Truth Behind the Fiction," which, according to the brochure, "explores the realities that inspired some of the most celebrated feature films in recent memory." A glance over the list of films make it clear that we shouldn't be too rigorous in analyzing the organizers' argument. In fact, I can't think of a feature film it could be related to, other than John Frankenheimer's "The Train" of 1964, or perhaps the Boulting Brothers hilarious "Private's Progress," of 1956, in which a terminally naive young academic becomes embroiled in his shifty uncle's scheme to loot Nazi loot. Still, I wish Mass MoCA's graphic designer hadn't set the word "TRUTH" in such big letters. A further reason to show the film vanished under sad circumstances. S. Lane Faison, former director of WCMA and professor emeritus at Williams, who, as one of the American officers in charge of recovering the artworks misappropriated by the Nazis, fell into the unlikely position of curator of Adolf Hitler's art collection, was to comment on the film, but he passed away on November 11 at the age of 98."The Rape of Europa" takes its title from the book by Lynn H. Nicholas (published in 1994 and hence also receding into the past), which tells the story of Nazi art policy, first a program to rid Germany of "degenerate art" and later a vast endeavor to acquire as much of Europe's artistic patrimony as possible for the museum Hitler planned to build in Linz, as well as for the private collections of his underlings, above all Hermann Goering. She concludes her book with the efforts of American and European officials to find and recover the works of art from their hiding places and to restore them to their original places, as well as the not uncommon thefts of artwork by souvenir-hunting American soldiers. As a painstakingly researched historical work by a non-academic historian it won considerable respect and a National Book Critics Circle Award, inspired an international symposium at the Bard Graduate Center in New York (published as "The Spoils of War" by Elizabeth Simpson), and provided the documentary foundation for the restitution movement, which has since resulted in the establishment of a plethora of organizations for the purpose of recovering works of art improperly acquired by the Nazis before and during the Second World War. This is all is very much in the news today, especially through the eye-popping events of the past six months.

After seeing the film, all I can say is "read the book." I understand it will be shown on PBS next year, and it could well become the vestige by which Mrs. Nicholas' book is remembered by non-specialists. I warmly hope that this won't happen, because it would be an injustice not least to Ms. Nicholas' scholarship, but also the historical record and the array of complexities which beset issues of cultural property. Many delicate situations are in the balance today, from American Indian artefacts to the unrecovered loot of various wars (including the recent US venture in Iraq) and the Elgin marbles. Each problem is different and requires its own solution. Public opinion often becomes a factor in these debates, whether it is relevant or not, and it is irresponsible to encourage non-specialists to think in the simplistic terms employed in this documentary, which at best is out of date, since some of the stories it tells look quite different today, months or more after the latest developments included in the film, and at its worst circulates vague half-truths about history and the ethics of recovery and restitution.

The word "documentary," already found unsatisfactory by the early 1930's, is still the most common term for non-fiction film, and because of its relation to the word "document" it implies an element of factual content or "TRUTH." Although more recent films like Al Gore's "An Inconvenient Truth" (There it is again!) adopt a milder voice, even younger audiences remember the short, declarative sentences of an authority like Edward R. Murrow, which traditionally opened such films, inspiring the expectation that viewers would acquire factual knowledge, or at least learn the true judgement to adopt about the facts. (We ignore this authoritarian aspect to our peril.) And one wouldn't have to survey many documentaries to realize that the genre is ill-suited to the communication of large amounts of detailed information. On the contrary, the best non-fiction films work through the emotions, and some of them become recognized as works of art because they do this so well. In these filmmakers maintain a constant effort to move the audience through images, sounds, music, and the rhythms of cutting. It's rare that one hears a non-fiction film praised for its research or the presentation of unknown images or information, pace exposé films like "Fahrenheit 9/11." Even there the primary thrust is in Michael Moore's approach and in the relationship of trust he builds with his audience, and without this foundation in the feelings harbored by the audience towards governmental conspiracy, it would fail to interest people, no matter how important the message. The point comes home when we see films that are recognized as some of the greatest of the genre, which make a powerful statement for beliefs that have become discredited or even detested, such as, for example, "The Triumph of the Will" or "Three Songs about Lenin."

I don't think anyone will be tempted to look at "The Rape of Europa" as a work of art, any more than the more estimable films by Michael Moore and Al Gore. Its aesthetics go nowhere beyond standard PBS fare. However, it becomes truly objectionable when, either through stupidity, sloppiness, or prejudice, it promotes facts so incomplete that they become meaningless or deceptive. The film tries to cover as many of the main topics in Mrs. Nicholas' book as it can without quite filling them all in and not always justifying their inclusion, as in the case of the allied bombing of Monte Cassino. The disposal of degenerate art, the conquest of Poland, the razing of Warsaw, the Czartoryski Leonardo (recovered) and Raphael (not), the forced purchase or theft of Jewish collections, ther seizure and collection of Jewish religious objects (The film never explains why the Nazis collected and stored these so carefully. It was for a Jewish museum, in which future purified Germans would come to view Jewish culture as we view dinosaurs today.), the depredations of Paris, the Italian campaign, and Russia (both what the Germans took from Russia and the Russians took from Germany) are inter-cut with contemporary restitution cases, obviously not taken from Mrs. Nicholas' book. In the main historical segments the omissions are merely obtuse, but the incompletely told restitution cases are deceptive. Events which occurred either as recently as last month or as long ago as eighteen months, events which have a crucial bearing on our understanding of these stories, are omitted, and we must assume that this is purposelytendentious. The makers let events run ahead of them, although the video editing technology of today would make it easy to cut in updates only weeks before theatrical release, as Michael Moore was able to do.

Although "The Rape of Europa" covers too much, if anything, it probably should have included the important case of the Lubomirski drawings, which is discussed briefly by Nicholas, because it brings together a contemporary restitution case (outside the purview of the Jewish organizations, since it involves a Polish public institution) and loopholes in the work of the "monuments men." Consisting of twenty-seven sheets by Dürer and his circle they were prime material for Hitler's museum. In 1823 (consummated by bequest in 1866) Prince Henryk Lubomirski donated his collection as a separate museum within the institute founded by his friend Count Jozef Maksymilian Ossolinski "for the preservation of Polish cultural heritage" in Lviv, which was then Lemberg, a city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The bequest stipulated that if the Ossolinski Institute were ever dissolved and not reformed within fifty years, the Lubomirski collection would revert to the family. After the end of the World War I, Lemberg became part of Poland, and its name was changed to Lvov. In 1939, as part of the Soviet-German non-aggression past, Lvov was assimilated by the Soviet Union. The Germans tried to obtain the drawings at this point but the Soviets refused. They dissolved the Ossolinski Institute and Lubomirski Museum and transferred the drawings to a state institution. The Germans then seized them when they invaded Russia in 1941. After the war the Americans found the drawings in the Alt Aussee salt mines near Salzburg. At the Potsdam Conference of 1946, Lvov was assigned to the Ukraine, which was under Soviet control, but by this point the Cold War was taking shape, and the American authorities became reluctant to return artefacts to the Soviet Union. The drawings remained at the Munich Collecting Point, while American restitution policy evolved. At first they only restored artworks to official organizations, but eventually they opened it up to religious and racial refugees, and finally to political refugees, which included the Lubomirskis. When Prince George Lubomirski filed for restitution of the drawings, promising to donate them to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, it caused much convoluted debate among the American authorities, but finally in 1950 the State Department, aware that Poland might exercise a strong claim over them, reluctantly made the decision to turn the drawings over to Prince George, who sold them all through dealers without informing the other members of the family, living comfortably off the proceeds until his death at the age of 91 in 1978. The Ossolinski institute has been reconstituted in Wroclaw, Poland (formerly Breslau in Germany) but part of the collection has remained in Ukraine, and both countries have made claims for the drawings, which are are now scattered about European and North American museums. The present situation is immensely complex and not likely to be resolved any time soon.

*

I'll begin with what the film does well, which is to impress on us the extraordinary scale of the Nazi's activities. Reichsarchitekt Hermann Giesler built models of the entire cultural zone Hitler planned for Linz, with a large museum a prominent part of it, and Hitler doted over them even in his final days, when he knew everything was lost. A vast network was established to gather up the most important works and send them to safe places until the war was won and the construction of the museum could begin. Often they were able simply to seize the art in the course of their conquests, for example in Poland and Russia. In other cases they were obliged to purchase it. The film implies that they always extorted the works, particularly from Jewish owners, at prices far below their true value. This was not always true. For example, Mrs. Nicholas' account of the overheated Paris art market during German occupation is both bizarre and chilling.

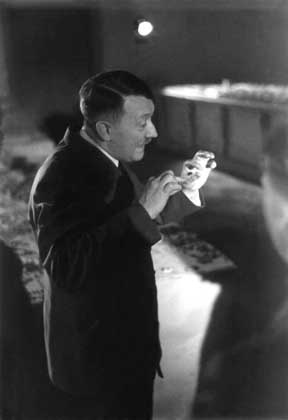

The character of Nazi collecting was itself bizarre—and banal. If Hitler was driven by an passionate obsession, which put the highest social value on his early, unsuccessful vocation as a watercolorist, Goering behaved like any crass parvenu, and other men in the Hitler's circle made the rivalry of collecting a social game, not unlike the people you see chatting in Sotheby's lobby today. On one level the Nazis took and distributed the spoils of war just as warring states have done for thousands of years. In their modern, systematized way they were acting out an atavistic impulse, as they prepared to build their future world. For them cultural treasures were like the numinous images which were venerated and carefully guarded in the innermost sanctuaries of ancient citadels, like the mythical Palladium of Troy, which had dropped from the sky and had the power to preserve the city from harm. The Greeks had to steal it before they could sack the city. On this level the Nazis were seizing magical images from their enemies and appropriating them and their cultural power for themselves. In the process they aped the behavior of the Jewish collectors they so despised. The film does not attempt this sort of interpretation, but in that context we can see something primal in Hitler's and Goering's preening, which comes across so vividly in the film clips.

If the Nazis were following an ancient tradition in pillaging the conquered, as had Napoleon and the British in Africa as recently as 1897, were they actually breaking a law? In fact they were, albeit a recent and untested one. The seizing of private property by conquering armies was outlawed by Article 49 of the 1907 Hague Convention and by the Kellog-Briand Pact of 1928, and Germany was a signatory of both. At the Nuremberg trials, Alfred Rosenberg, whom Hitler had placed at the head of a special unit in charge of acquiring art (a key figure mentioned only in passing in the film), was accused and convicted of the "looting and destruction of works of art," among other war crimes, and was hanged.

"The Rape of Europa" is fraught with inaccuracies, and they begin early. The narration laments the low price, $1600, at which Picasso's "Buste de femme àla chemise" of 1922 (22 x 18 in.) was sold in a 1937 auction of degenerate art. Actually that seems like a rather strong price for a small work from Picasso's classical period at that time, but if the bidding was not lively at these auctions, it was because many American museums and collectors boycotted them, knowing that the proceeds would fill the coffers of the NSDAP. We see the painting in the sale room, going for $6,826,000 and are invited to be suitably appalled. The filmmakers are in general cavalier about values. When a Polish curator made the somewhat ridiculous assertion that the lost Raphael portrait from the Czartoryski Museum in Cracow would sell for $100m, it was left unchallenged. If the "Madonna of the Pinks" sold for $40m in 2004, even if possibly not at the highest attainable price, I doubt the portrait would fetch that much more, even though the homo-erotic qualities modern buyers might see in it would make it highly saleable.

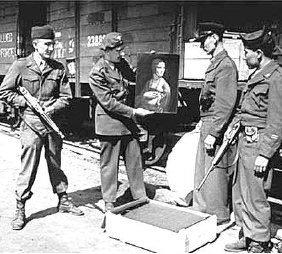

The treatment of the Italian campaign in the film is an unfocussed checkerboard of massive destruction followed by successes and rescues. I suppose the filmmakers wish to show that the allies were also guilty of destroying art, and that the Germans and their Italian allies exploited it to the fullest in their propaganda. Throughout the film the makers show themselves to be particularly enamored of the "monuments men," an international, preponderantly American group of military personnel assigned to the task of rescuing damaged works and, after the war, collecting them and restoring them to the responsible organizations. Among them were the most prominent names in the American art world of subsequent generations: Frederick Hartt, James Rorimer, and of course Mr. Faison among others. They rightly treat the Camposanto of Pisa at length, focussing on Deane Keller, still without quite bringing him or his dedication to life. Nothing is said about the Italian Rodolfo Siviero, one of the most important people of all, but much about Rose Valland, the curator at the Jeu de Paume who documented the movements of art appropriated by the Nazis.

In the case of Monte Cassino, the most prominent Allied blunder, the religious significance of the Abbey was primary in the public mind. Within days the Germans mounted campaigns in Catholic countries like Spain to show that the Allies were hostile to the Church. Important objects from Naples had been deposited at the Abbey, but the Germans moved most everything that could be moved to Spoleto, whence they found their way to the Vatican for safekeeping. The Abbey itself, with its medieval frescoes and monumental door that was the greatest loss. A veteran, whose connection with the series of assaults on Monte Cassino was not stated, spoke only in generalities, giving us no real idea of what the disastrous series of battles at Monte Cassino was really about, as well as a disproportionate view of the American role in them. There is no shortage of better sources about the battle, as the excellent "WWII People's War" section of the BBC site shows.

The Americans were followed by New Zealanders, and finally the Poles launched the final, successful attack. After months of combat the Allied soldiers had come to hate the Abbey, which seemed impregnable on its mountaintop. It became a canker to morale. They didn't know whether the Germans were within the Abbey, or only around it, respecting its status as a cultural monument, as they claimed. General Freyberg of the New Zealand Brigade pressured the Supreme Allied Commander, General Alexander, to bomb the Abbey, but he resisted, as long as there was no proof that the Germans were actually in the Abbey. Years later the story circulated that the decision to bomb was based on an intelligence officer's error, as Rupert Clarke relates in his memoirs. The Allies intercepted a radio transmission in which the question, "Ist Abt im Kloster?" was answered in the affirmative. The translator took "Abt" to be an abbreviation of "Abteilung" the German word for "division" rather than its proper meaning, "abbot." This gave the bombing enthusiasts the prestext they needed. The destruction of the Abbey only made things worse for the Allies—much worse. The Germans, who had indeed remained outside the Abbey were now able to make a very effective fortress of its ruins, and reinforcements were parachuted in, while the allies struggled to get around the debris the bombing had created. It took another four months after the bombing, before the Poles captured the ruins. Monte Cassino proved a disaster in loss of life, winning the war, and public relations.

This kind of weak research and presentation inspires suspicion, and when archival footage is inter-cut and interpreted by the narration, I found myself becoming increasingly sceptical. When a still of Hitler making a grasping gesture, in which he actually outdoes Charlie Chaplin, cut to a film of running German soldiers, I couldn't help wondering, "What were they really doing?" This greatly weakens the ultimate power of the film. I was delighted to be able to find out what Hitler was actually doing in this Chaplinesque moment: he was showing off his beloved model of Linz. These are not grasping hands, but the moulding hands of an artist.

If the treatment of history is off the mark, it shows weak research and film-making; however, potential danger lies their disingenuously incomplete account of contemporary restitution cases. As I mentioned, during the 1990's various factors, including Mrs. Nicholas' book, stimulated a wave of investigations into the provenance of artworks in public and private collections around the world. Today there are several watchdog organizations devoted to the recovery of art improperly acquired by the Nazis from Jewish collections, museums devote considerable staff time to researching the provenance of works acquired since 1933, and auction houses and dealers find themselves obliged to verify this phase of the provenance of their wares.

*

Nancy Yeide, Curator of Records at the National Gallery of Art, found in a straightforward Internet search that a painting seized by the Nazis from Paris dealer Jacques Seligmann, "Les jeunes amoureux," a cabinet picture (11 x 14 in.) by François Boucher, was on display at the Utah Museum of Art, a donation by a patron, who had purchased it from the Newhouse Gallery in New York in 1972. The filmmakers interviewed Yeide and videotaped (or obtained a tape) of Seligmann's heirs, his eldest daughter, Claude Seligmann Délibes and the widow of his son, Suzanne Geiss (Seligmann) Robbins, receiving the meticulously packed painting in a small ceremony at the beginning of April, 2004. In the tape the tearful Mrs. Délibes "expressed deep gratitude to the museum and its staff for their ethical handling of the investigation and their willingness to return it." Mrs. Délibes said she had never paid much attention to recovering her father's stock until 1999, when she and her sister-in-law first received one of the missing works. Then she became more active. When asked about their plans for the painting, they said, "We don't know." Two and a half months later "Les jeunes amoureux," appeared at Christie's New York (sale June 17, 2004, estimate $200,000 - 300,000) which is pretty fast work for the auction market. The opinion of the Boucher expert Alastair Laing had to be provided on the basis of a photograph and a transparency. Joint ownership of art can be problematic, particularly if through a family tie through marriage, but the Seligmann heirs had been reclaiming art work for five years and must have worked out a game plan between themselves. When interviewed and asked about the estimate on the eve of the sale, Mrs. Délibes said that "it could go for a lot more." At the auction the bids failed to meet the reserve and it was bought in—surprisingly, because it is a fine work. So far, I've been unable to trace the painting. The result of this fair restitution is that a painting which was on public view in a museum has now disappeared. Presumably it hangs in the home of Mrs. Délibes or Mrs. Robbins, until its singed feathers cool off.

*

"The Rape of Europa" also features a much-publicized case, that of the five paintings by Gustav Klimt which formerly hung in the National Gallery of Art in Vienna, all but one for over fifty years. They were commissioned or purchased by Adele and Ferdinand Bloch-Bauer in the first quarter of the twentieth century and include two portraits of Adele. In her will dated two years before her premature death in 1925, she instructed her husband to donate four of the Klimts to the National Gallery. After the Anschluss of Austria in 1938 Ferdinand and his niece and heir, Maria Altmann, fled, leaving behind the paintings. He settled in Los Angeles in 1942, became an American citizen in 1945, and died the following year in Zurich. The Nazis had taken possession of the paintings after they fled and deposited them in the National Gallery and other Austrian museums. Just before he died he hired a family friend who was a lawyer to get the paintings back from the Gallery, and in his will he did not follow through with Adele's wish to bequeath them to the Gallery. He left all his possessions to Maria Altmann and her siblings. In 1948 the lawyer signed over the Klimts to the Gallery in exchange for an export permit. Altmann claims she was not aware of this deal, believing that her aunt and uncle had donated the paintings before the war.

In 1998 the Gallery's archives were made public to confirm that they did not possess looted artworks, but an Austrian journalist discovered that the Klimts had not been properly donated. Maria Altmann, by then the sole surviving heir, filed for the return of the paintings at the end of that year. Six months later the Austrian Advisory Board rejected her claim, because they found that the donation of the paintings was not done under coercion. When the Board refused to cut a deal with her, she filed suit in Austria, but she was unable or unwilling to pay the substantial filing fee required by Austria and many other countries, but not the United States. Although Austria reduced the fee substantially for her, she decided to sue Austria in a Los Angeles court. The Austrians "maintain[ed], as they have for over 50 years, that, under Austrian law, the [1923} will [of Adele] and Ferdinand's subsequent conduct gave the Republic [of Austria] ownership of the paintings." Austria petitioned Judge Florence-Marie Cooper to dismiss the lawsuit on the grounds that she had no jurisdiction over the suit under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act of 1976 (FSIA). Altmann claimed an exemption on the basis of an expropriation exemption involving "property taken in violation of international law." Austria rejected the exemption clause because it did not exist in 1948 and was not retroactive. However Judge Cooper found that it was indeed retroactive, both because of the Nazis' expropriation of the paintings from Ferdinand because he was a Jew and because of the deal to obtain export licences. Also, the National Gallery, an agent of the Austrian government, is engaged in commercial activity in the US because it published a book, an exhibition catalogue, and advertising featuring the Klimts. (American museums must find it interesting to learn that their exhibition catalogues, which are often sold at a loss, are now considered a commercial activity!) She also judged that Austria was not an adequate forum for the suit, because of the filing fee and its 30-year statute of limitations. The Austrian government then appealed the case up to the Supreme Court, which ruled in June 2004 that the FSIA was indeed retroactive. Austria made a second attempt to get the case dismissed, but again the American court ruled in Mrs. Altmann's favor.

Her sale of one of the portraits of Adele Bloch-Bauer to Ronald Lauder for $135m this past June should be familiar to anyone who reads newspapers. This is the highest price ever paid for any work of art. Once again the winner of a restitution case has gone straight for the money. Some reports say that Mr. Lauder negotiated the sale directly with Mrs. Altmann, others that Christie's acted as broker. It becomes curiouser and curiouser, when we learn that Mr. Lauder sits as Chairman of the Commission for Art Recovery of the World Jewish Congress, a sub-organization he himself founded in 1997. Lauder, as Nathaniel Popper reports in Forward, has been accused of hypocrisy by leading holocaust authorities because he, through this organization, has demanded that museums make the provenance of every work in their collections accessible to the public, while neither his museum, nor he himself, have carried out this directive. He has also been criticised for buying restituted art, while occupying this position. Indeed, his behavior in buying the Klimt is remarkable. First, he privately pays the highest sum ever paid for a painting, and then, when the sale of the four other Klimts at Christie's is announced, he publicly declares his interest in one or more of the others—something a serious potential bidder would never do, if he wants to hold on to his assets. Furthermore he displays the four paintings alongside his in the Neue Galerie. (If the Metropolitan Museum were knowingly to display works about to go on sale at auction it would be considered shockingly unethical. Note that the five paintings were shown at the LA County Museum between April 4 and June 30. The sale of Adele I was announced on June 19. "The Rape of Europa" showed Mrs. Altmann in the LACMA galleries, but it said nothing about the sale.) Mr. Lauder is not only buying restituted art, he appears to be inflating the value of such works by paying this astronomical price for one and then talking up the remainder which were to go to auction. Souren Melikian has already noted this in the International Herald Tribune (11/9/06) in his report of the sale, which this past November 8th, set an all-time record of $491m. He also described the second portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, which sold for $87,900,000 at the sale, as "blandly sentimental, bordering, some would say, on kitsch,"a description which might apply the the first one as well, not to mention the vulgarity of its gold background. (If Klimt took his inspiration from the wonderful Ravenna mosaics, that no excuse, but it does invite interesting historical parallels between the Jewish haute bourgeoisie of 1920's Vienna and the displaced successors of Augustus.) As my late father would have said, "the monkey is in charge of the bananas." Even more entertaining is the story of Anita Halpin, the chairman of the Communist Party of Great Britain, who was awarded a Kirchner from the walls of Die Brücke Museum in Berlin and sold it at the Christie's sale for $38m—to Ronald Lauder! Today she is one very rich Communist.

On the other hand the Austrian press, at least the major paper Die Presse, took a positive view of Maria Altmann and her claim. Her elegance (She ran a fashion boutique for many years, retiring at the age of 85.), good manners, and education charmed many Austrians, and the Anglophone press has not properly stressed the fact that she made her first offer to sell the paintings to the Austrian government. She also kept the paintings in Austria for an extended period, reserved for Austrian buyers. After none came forth—for whatever price she was asking...we can assume it was very high—she had the paintings shipped to Los Angeles, where they were immediately put on the walls at LACMA.

However attractive Mrs. Altmann may be as a person, the events surrounding her Klimts since they arrived in the United States have defied traditional art world ethics—not that they in reality are little more than moral origami, commonly blown away with a mild puff. Michael Kimmelmann, writing in the New York Times on September 19 made a valid point, when he wondered why she couldn't have given just one of the Klimts to a museum, or sold one or more of them at a reduced price to a deserving institution like LACMA, which helped her to tout the works she intended to sell. Mr. Kimmelmann and other people in the field, including myself, consider the least valuable of the paintings, the "Birch Forest," to be the best of the group. Why not that one? It is also curious, that, while it was known that the works were offered for sale in Austria, she publicly concealed her intention to sell in the US? At least we know that Adele I is on public view, albeit in Ronald Lauder's private museum, and that he can afford it. Then, since holocaust restitutions are not taxed under US law, Mrs. Altmann will not have to pay taxes on her share of the painting, removing the last incentive to make a donation.

Both of the restitution cases so partially presented in this fatuous and dishonest documentary have put the whole movement in a bad light, and they serve neither the museums which have been preserving these works of art for the public nor the descendants of holocaust victims with rightful claims. At the same momentous sale in November there was a painting that did not sell. Picasso's "Portrait of Angel Fernández de Soto" offered by Christie's with a high estimate of $60m, was pulled from the sale at the last minute. An heir to its original owner launched a last-minute "ambush" claim that his ancestor had sold it as a result of Nazi persecution. Although the judge threw out the case, Christie's didn't dare take the risk. This is madness. In an article inspired by the sale, http://www.theartnewspaper.com/article01.asp?id=526 Georgina Adam wrote about Nazi bounty hunters, that is lawyers who see a gold mine in restitution cases. Some work on a contingency basis like E. Randol Schoenberg, grandson of the composer, who gets 40% of Mrs. Altmann's takings. There are also venture capitalists eager to finance these legal ventures. In "The Rape of Europa" we are not witnessing the workings of justice, as the filmmakers would have us believe, but merely big business in action. For my part I find this feeding frenzy in the sale rooms as disturbing as the similar eruption in the art market in wartime Paris.

What did Adele Bloch-Bauer, Hitler, and Goering have in common? Curiously, for them art had some value beyond money. Even Jacques Seligmann had his moments, as do many art dealers, it may surprise you to learn. Family tradition has it that he threw a potentially lucrative customer out of his gallery, Hermann Goering himself. It is indeed sad to see the heirs of these early owners, pausing only for a few public tears, reverse the priorities so readily. I'll try to close on a brighter note, with another tidbit not mentioned in the film. The Picasso Buste de Femme sold by the Nazis as degenerate art was bought by the great collector René Gaffé, who bequeathed his entire collection to UNICEF. When it sold at Christie's for $6,826,000 in November 2001, that money went to UNICEF's invaluable work for the children of the world.