Ai Weiwei at Mary Boone and the Hirshorn Museum

Forge Evokes 5,200 Lost Schoolchildren

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 15, 2012

Ai Weiwei: According to What

Hirshorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Washington, D.C.

Through February 24, 2013

Ai Weiwei: Forge

Mary Boone Gallery

541 West 24 Street

New York City, New York

Through December 21

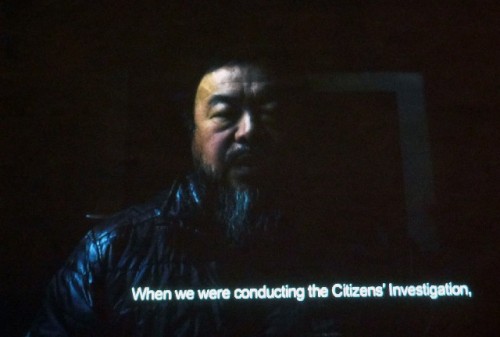

Because the Chinese government has revoked his passport, the world’s most renowned and respected dissident artist, Ai Weiwei, was unable to travel to the United States for the retrospective, Ai Weiwei: According to What, one of the most important global exhibitions of the year, which continues at the Hirshorn Museum, in Washington, D.C. through February 24.

We plan to see the exhibition and urge you to visit the Mary Boone Gallery exhibition, Ai Weiwei: Forge, which remains on view through December 21.

The New York gallerist, Mary Boone, is not noted for the acuity of her moral compass. One may speculate that it is the celebrity of the artist, and the bankable, collectable status of the work, that motivated the exhibition. It is not the kind of commercially viable, big ticket art that one normally encounters in the vast Chelsea space.

It is rare to encounter work in her gallery that entails such intensive gaze and profound, indeed shattering, and disturbing, soul searching contemplation.

As is often the case with this artist what we see is typically simple in its materials and forms but densely layered and embedded with meaning.

Upon entering the gallery we first encounter a bare tree, with truncated, pruned branches. Fabricated from carved marble.

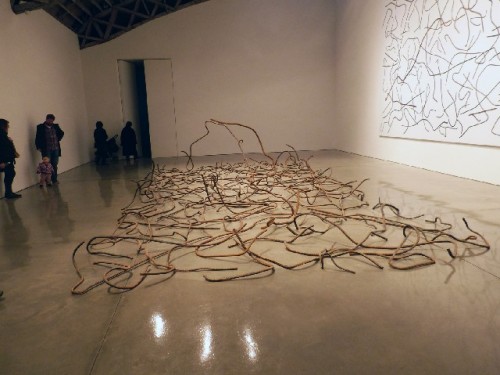

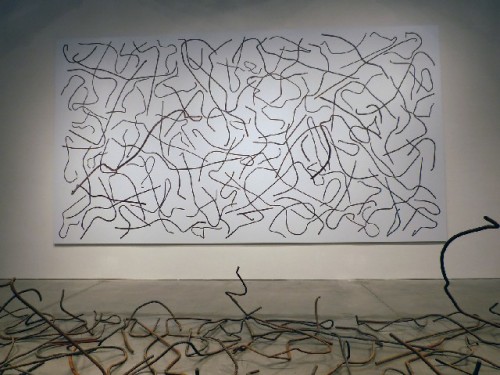

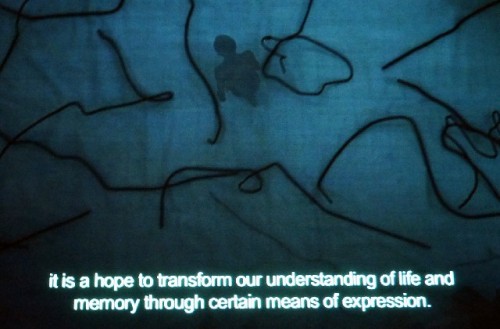

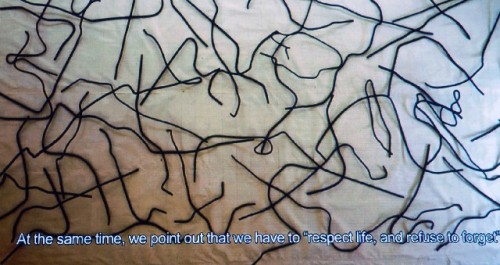

In the large vaulted gallery space we view a squared off area of twisted metal bars on the floor. On a wall, centered above this area, is a graphic image seemingly offering a two-dimensional, bird’s eye view of the twisted forms set upon a white field.

The most direct response is to consider the metal as sculpture and the large, hovering, graphic image as a painting.

Well: Yes, no, and maybe.

First the painting may look like a painting but it is not a painting because it does not appear to be painted.

It is not clear by what process it has been created. Has it been drawn or painted by hand? Or is it a photograph? Possibly a silk screen or some other graphic process?

However it has been fabricated the more important point is that it mirrors the forms of the metal elements arranged on the floor.

In what aspect may we regard that configuration as sculpture?

Surely it entails metal a normal material for making sculpture. But does it belong to the category of Dada Found Object in the tradition of Duchamp? Or, through its apparent aspects of fabrication, an Assisted Readymade?

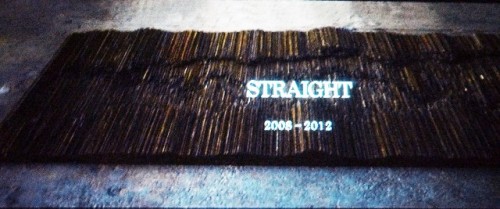

Because of the political issues that inform the projects of “Straight” (in the Hirshorn exhibition) and “Forge” (at Mary Boone) does it fall within the domain of the actions and Social Sculpture traditions of Joseph Beuys? Might one approach these works through the matrix of theories of conceptualism?

Let’s add the idea of relics to our discussion. This elevates an object from the realm of art to religion and metaphysics. It adds an element of prayer, contemplation, and spirituality.

In the Roman Catholic tradition, particularly during the Middle Ages, the faithful made pilgrimages to churches and cathedrals to visit and pray over the shrines and shards of saints. This process provided the opportunity to be forgiven or absolved of sin with the hope of being redeemed in the after life. The ultimate pilgrimage was to visit the Church of the Holy Sepulcher believed to be erected over the tomb of Jesus in Jerusalem.

All of these issues and arguments come into play in viewing the installation of twisted metal in the upscale, New York gallery.

The average visitor, making the weekend rounds of Chelsea galleries, may enter and leave quite quickly. Not knowing the work of Weiwei they might find that there is not much to look at. There is no immediate beauty or meaning to what is displayed beyond regarding a cluster of twisted metal. There might be resentment at yet another example of The Emperor’s Clothes and the usual hocus pocus of the upscale art world.

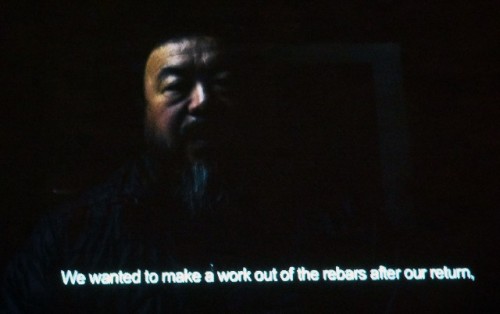

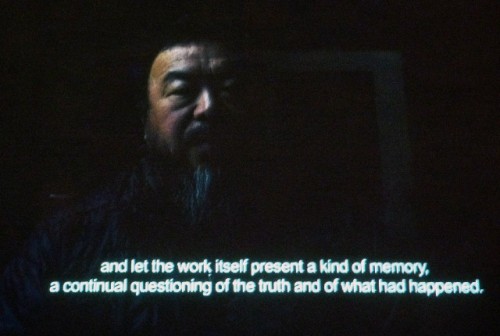

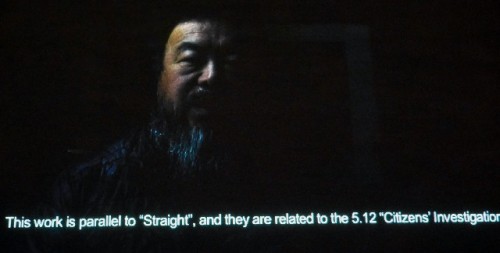

For a better understanding of “Forge” it is essential to spend time in the office of the gallery where a video produced by the artist explores the complex project.

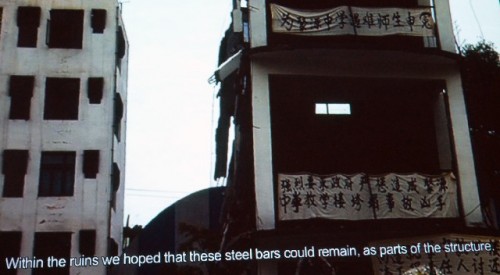

It is yet another of his many, indeed obsessive, responses to the tragedy of the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake. Because of cost cutting “tofu” construction The Beichuan Middle School collapsed resulting in the death of 5,200 schoolchildren.

The Communist regime of China engaged in a total coverup of the incident, its complicity, and even refused to release a list of the names of the victims. As an individual artist, with considerable resources and a profound sense of moral and social conscience, Weiwie became obsessed with ways of communicating and keeping alive the identity and names of the children.

This effort has taken different forms. The first objective was to undertake extensive research to compile and post the names of the fallen. These names were later read aloud in ritual ceremonies. Using different colored back packs, like those recovered from the wreckage, the artist spelled out slogans as relief sculpture on the exterior of exhibition spaces.

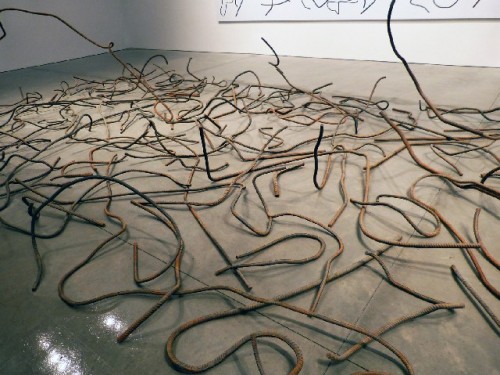

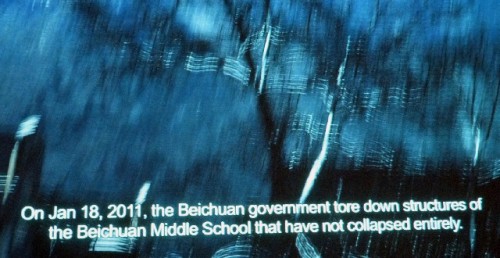

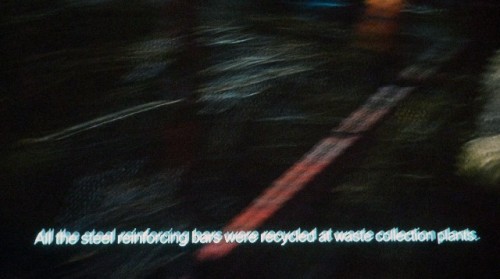

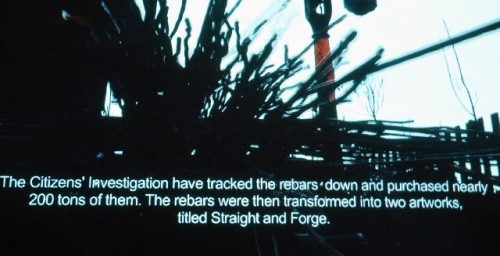

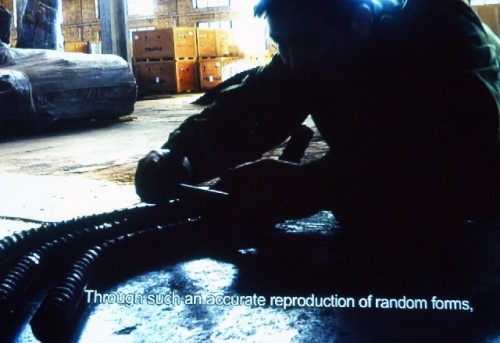

The materials of the now razed site were recycled as scrap. The artist purchased some 200 tons of the metal bars used as elements in the reinforced concrete construction which failed to meet potential earthquake standards.

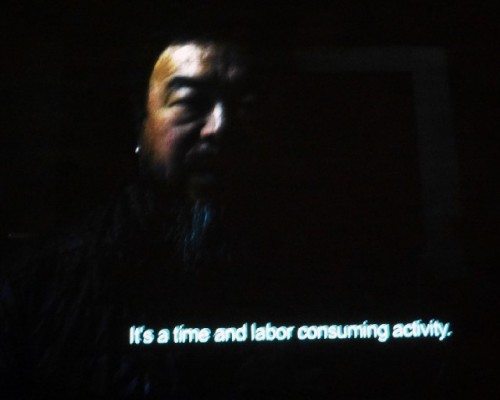

Typically, the artist employs many assistants and artisans to fabricate his projects.

The twisted scrap metal resulted in two large works: “Straight” and “Forge.”

For the first “sculpture” the metal bars were returned to their original form then stacked as “Straight.”

With “Forge” the straightened metal rods were then meticulously bent and reformed to exactly replicate some of the recovered elements.

Logically, one asks why the artist might not have simply selected example of the twisted debris? Why laboriously straighten and then reform them with seemingly random end results?

One may only make sense of this labor intensive and expensive process as the artistic equivalent of a medieval pilgrimage and prayer vigil. For the artist, and his legion of assistants, it was a form of meditation on the souls and memories of the lost children which the government would rather just bury.

Not surprisingly, the regime responded to the efforts of the artist, exposing their callous corruption and complicity in the mass death of children, with unmitigated rage, assault, incarceration, sustained repression and persecution.

The Chinese authorities stopped just short of murder or execution. These are possibilities that Wewei in numerous interviews has acknowledged as distinct possibilities.

What keeps him alive, and sustains his reputation as our most important and influential living artist, is that to execute him would elevate Weiwei from a dissident to a martyr.

While the economy and industrial power of China continues to expand the powerful work of Ai Wewei keeps vivid that nation’s horrendous legacy of human rights violations. Through his work the memory of lost children has not been reduced to rubble.

That message is particularly poignant today as Americans respond to yet another massacre of toddlers and their teachers in Connecticut. It is important to remind ourselves that children die every day in the war zones of Syria, Afghanistan and around the world. Let us mourn lost children everywhere. They are all precious loved ones.

Link to coverage of the video Ai Weiwei; Never Sorry screened during the Berkshire International Film Fesitval