Legendary Diacono Gallery Resurfaces

Man in Space Variations on a Bauhaus Theme

By: Mario Diacono - Dec 13, 2024

Bauhaus ?

Diacono Gallery

December 11-21, January 4-11

14 Beacon Street, Sub Basement

Boston, Ma.

857 423 6230

Wednesday-Saturday 12:00 to 6:00

diaconogallery@gmail.com

Man in Space

Variations on a Bauhaus Theme

In 1931, in the midst of a divorce, Margaret Egloff, of Boston, moved to Zurich with her two children, to study with Carl Gustav Jung. As part of that psychoanalytic training, she painted about forty-five watercolors likely dictated by her dreams, as Jung’s practice required. For a short time that year, she had an affair with the novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose wife Zelda was in a sanitarium in Zurich.

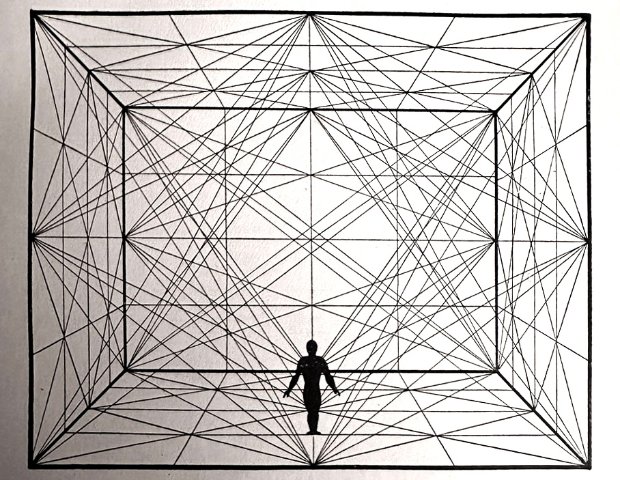

Margaret’s watercolors were discovered in a portfolio sometime after her death in 1998. In 2020 there also appeared in the estate of her son Frank a previously unknown sculpture, of metal wire; a sculpture extraordinarily similar to a well-known drawing by Oscar Schlemmer, reproduced on page 13 of the book he published with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in 1924, Die Bühne im Bauhaus, as fourth in the series of the Bauhaus Bücher. No trace of such a sculpture has been found in either the Schlemmer or the Bauhaus archives, but given the incredible resemblance of this work to the drawing published in Die Bühne im Bauhaus, we tentatively propose that it was created within the circle of students or alumni of the Bauhaus, at about the same time as Margaret Egloff’s study with Jung in Zurich and her European travel with Fitzgerald. There is a profound logic to the possibility that she saw it and collected it, eventually giving or leaving it to her son, a psychiatrist as well. The Schlemmer image would have certainly appealed to a student of Jung, as the anonymous sculptor places Man at the center of an almost infinite abstract space, no longer that of a theater but rather of a universal system.

As a variation on Schlemmer’s drawing, this singular sculpture strikes us as an expressionistic, symbolic representation of existential anxiety for the artist in between twentieth century’s two world wars, a meditation on the coming supremacy of industrial technology over the humanistic view of life.

At the same time, the sculpture also appears as the unexpected, unrecorded, physical representation of Schlemmer’s theory of a mechanized theatrical stage: “Man, the animate being, would be banned from view in this mechanistic organism. He would stand as ‘the perfect engineer’ at the central switchboard…” *: Leonardo’s Vitruvian man shrunk from microcosm, a measure of the cosmos, to mere function of a mechanized space, an appendix of the machine. Obviously Schlemmer used the word “Man” not in a gender-defining sense but as a shorthand for ‘Human’: when he creates a figure to perfectly activate the space of his Bauhaus stage, he names it simply “the dancer”, who can be either a man or a woman. But by placing the dancer’s figure at the center of a universal space rather than of the theatrical stage as it appears in Schlemmer’s drawing, the anonymous Bauhaus artist has radically changed the meaning of the images’ lines as spatial signifiers.

While Schlemmer’s drawing inscribes a three-dimensional space, this sculpture (whose dimensions are 18”x16”x5”)** clearly evokes, instead, the bi-dimensionality of the drawing itself. Further, by adding a graphic dimension to traditional sculpture, the work previews an early Minimalism. The anonymous artist doesn’t only follow the structure of Schlemmer’s drawing but also the spirit of the text accompanying it: on giving physical presence to “the cubical space” as an “invisible linear network of planimetric and stereometric relationships”, he builds a sculpture of pure geometry as we have seen it fully practiced in the early 1960s. In addition, by placing the human figure, molded in an expressionist mode akin to that of Alberto Giacometti’s works of the 1940s and 1950s, at the center of a universal space, he seems to follow Schlemmer’s coupling of the “laws of cubical spaces” with the “the laws of organic man […] invisibly involved with all these laws […] Man as Dancer (Tänzermensch). He obeys the laws of the body as well as the law of space: he follows his sense of himself as well of his sense of embracing space”, as illustrated in a drawing on the following page 14 of Die Bühne im Bauhaus. In not limiting him or herself as an epigone: the anonymous Bauhaus disciple pushes his master’s imagination further, making his work inspired by Schlemmer’s drawing not merely the illustration of an idea, but an idea itself, anchored not in the physical world but in a metaphysical realm.

Mario Diacono

*The Theater of the Bauhaus. Edited and with an introduction by Walter Gropius. Translated by Arthur S. Wensinger, Wesleyan University Press, 1961.

**As an accidental exercise in proportionality, it corresponds in inches to the dimensions of our exhibition space in feet.