Ai Weiwei Shown in Three NY Galleries

Lisson, Mary Boone and Jeffrey Deitch

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 13, 2016

Ai Weiwei

2016: Roots and Branches

Mary Boone Gallery

Lisson Gallery

Laundromat

Jeffrey Deitch Gallery

Through December 23

After four years of war it is reported that today rebel forces in Aleppo, Syria will surrender to the regime of President Bashar al-Assad backed by Russia and Iran.

There have been accounts of Government troops going house to house slaughtering civilians. Prior to this the media has regularly covered mass executions as well as relentless strikes by Soviet planes and barrel bombing of residential targets.

The ongoing war by the al-Assad regime, a genocide of his own people, has caused mass migrations of refugees flooding into and destabilizing neighbors like overwhelmed Jordan and Turkey aas well as European nations. Anti-immigrant responses have fueled the endemic rise of nationalist, far right political parties.

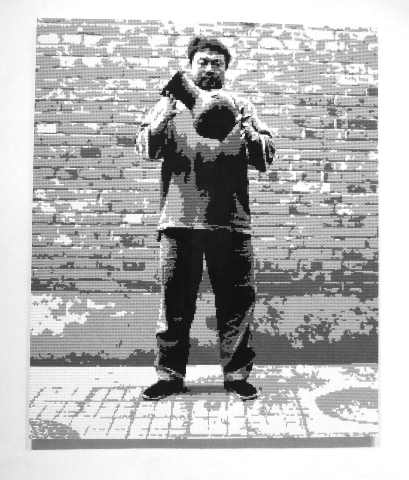

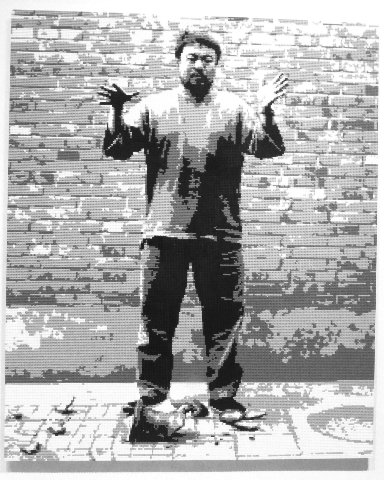

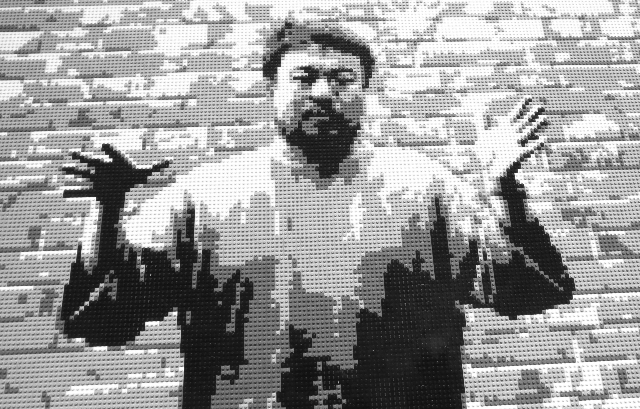

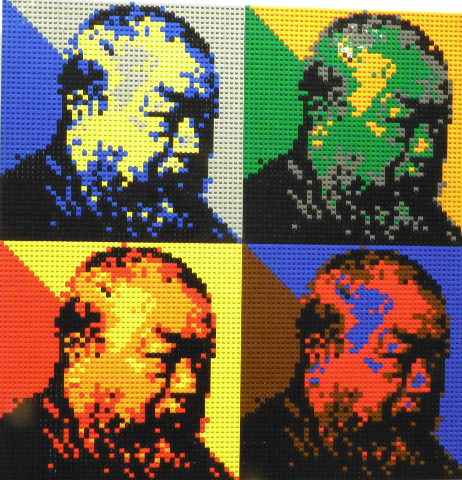

In three concurrent New York gallery exhibitions the dissident Chinese artist, Ai Weiwei, has created poignant and roiling new works.

Pursuing the signature aspects of his renowned work viewing it takes on the form of labor intensive contemplation of materials, documents, traditional and experimental techniques that congeal into an absorbing and emotionally devastating confluence of art and politics.

The artist, arguably the most controversial and renowned of his generation, adroitly combines elements of East and West. There is both a deep immersion in Chinese imagery and traditions as well as a cutting edge presentation abreast with the most advanced developments of multi-media experimental contemporary art.

As one of the most successful global artists there is enormous demand for his work.

This has led to factory-like studios in China, where he was confined by the Government, as well as more recently in Berlin.

There is often an obsessive-compulsive aspect to his projects. For Turbine Hall, at London’s Tate Modern, his associates created millions of ceramic sunflower seeds. In another labor-intensive project, previously show at Mary Boone, assistants collected and then straightened rebar rods from a collapsed school which resulted in the covered-up death of countless children. The destruction resulted from substandard construction that collapsed as the result of an earthquake.

Now that he has regained a passport, having being imprisoned and tortured in China, the artist has traveled to Syrian refugee camps to witness their deplorable conditions. Yet again that launched an ongoing, multi-valent project.

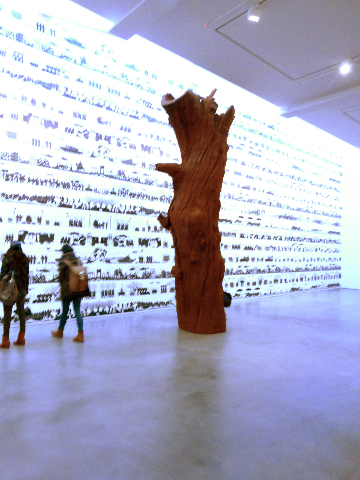

Entering the Lisson and Mary Boone galleries there are similar but slightly different impressions.

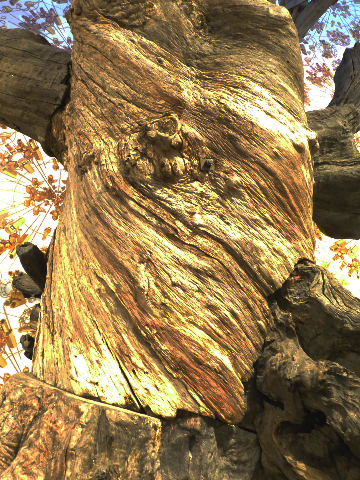

Both installations feature the titular Roots and Branches.

These evoke traditional Asian metaphors of time, nature and the manner in which, by extension, the human condition is gnarled and weathered. There is an equivalence to found Scholar’s Rocks like the one in front of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

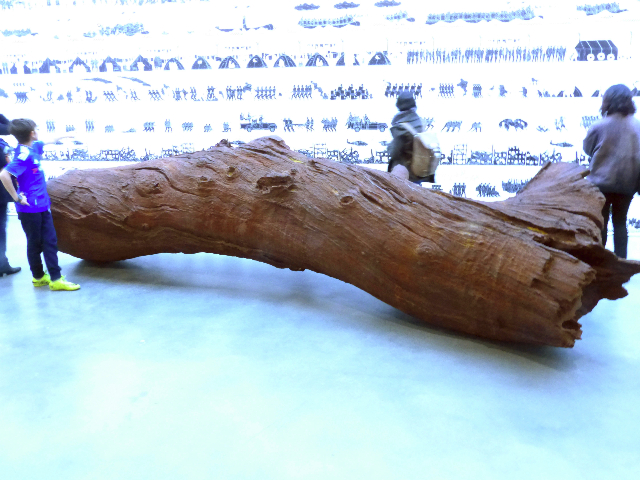

At Lisson we encounter several large, rusted, cast iron sculptures. They either sprawl low to the floor as stumps with unearthed, exposed, spidery roots. A couple are large, decayed trunks of trees while another extends in an earth bound horizontal configuration.

There is the dichotomy of the replication of nature, the seemingly mundane detritus of a primeval forest, and its complex and expensive reproduction as rusting metal. We confront the conundrum of why one would take the time, trouble and expense of casting a huge tree in a less than noble metal, iron rather than bronze.

We also encounter trees and branches at Mary Boone but in this case the actual materials. We examine how they have been cut into sections then bolted together in their original configurations.

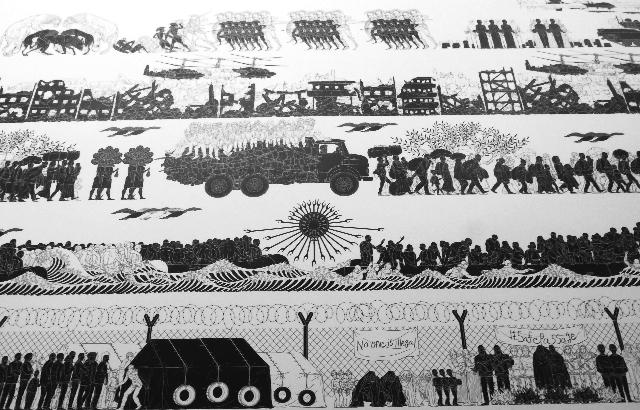

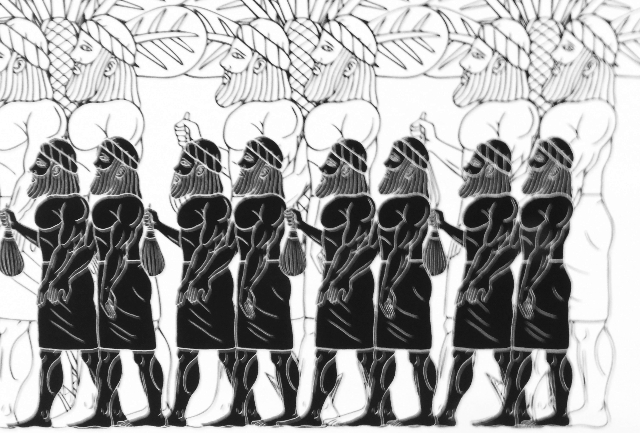

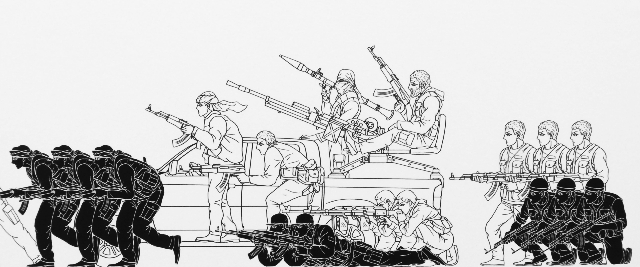

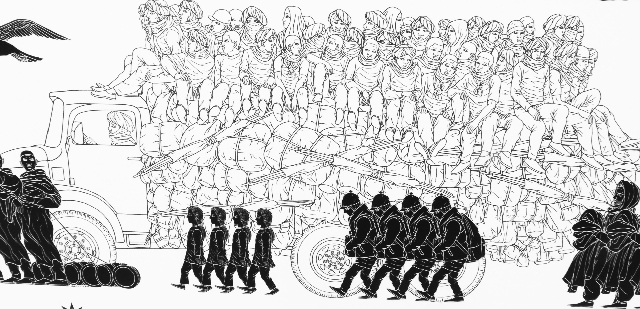

For both galleries there is wallpaper. At Lission we stand before stacked rows of figurative friezes. The wall at Boone is covered with decorative gold patterns.

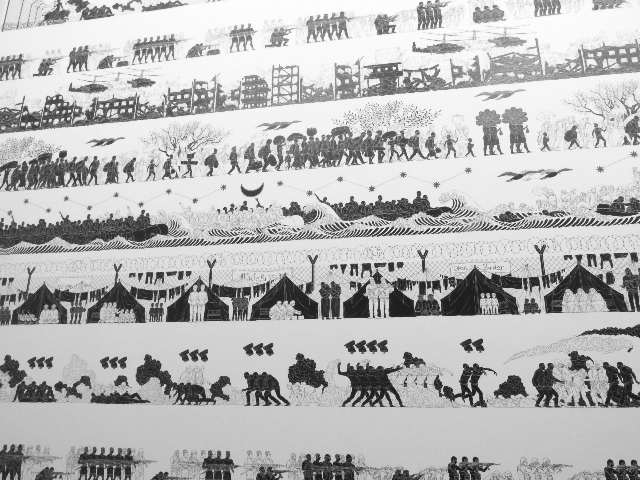

Upon closer examination there is an intensive narrative in the complex Lisson design.

There is the immediate challenge of time and critical attention.

With so much going on the viewer must make a decision. Either one takes it all in as a sweeping panorama, a background behind the metal sculptures. Or make a commitment to slow down and absorb the intentionality of the dense bands.

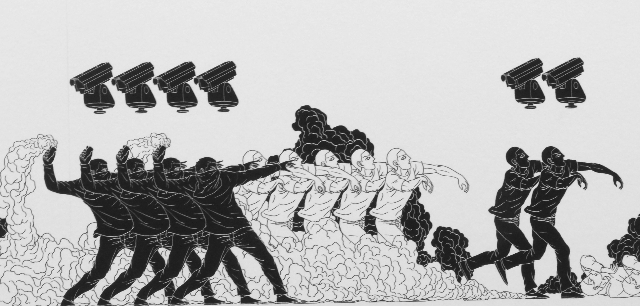

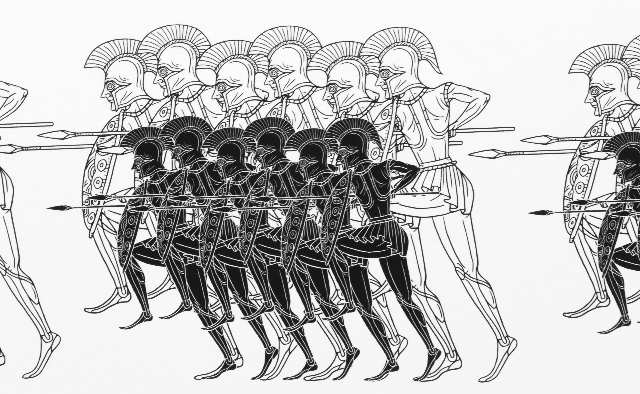

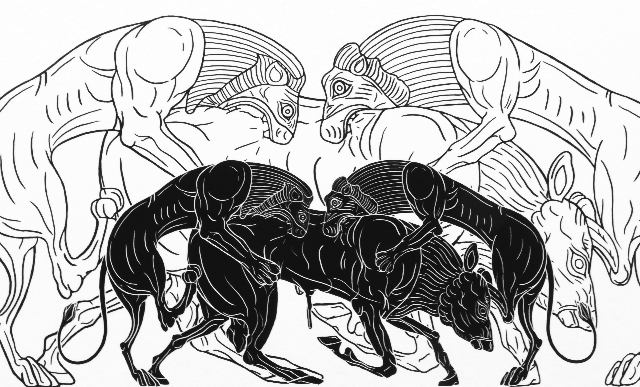

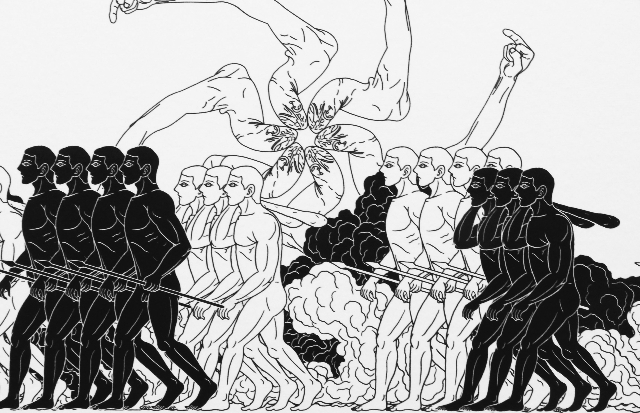

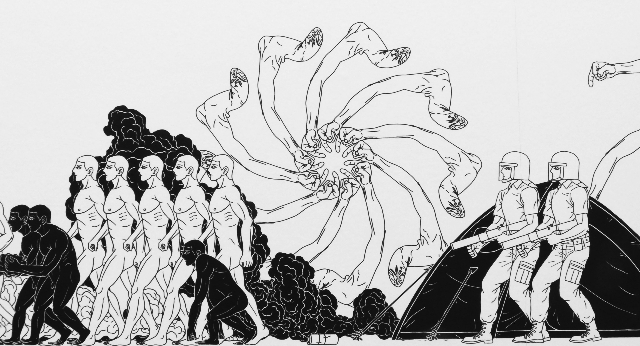

Here the artists and his graphic assistants have created a visual narrative the equivalent of the ancient Greek Homeric epic poem The Iliad.

That notion is hardly a stretch.

The associations that conflate ancient Greek art and literature, elements of ancient Assyrian, Egyptian and Roman art with contemporary war narratives are specific.

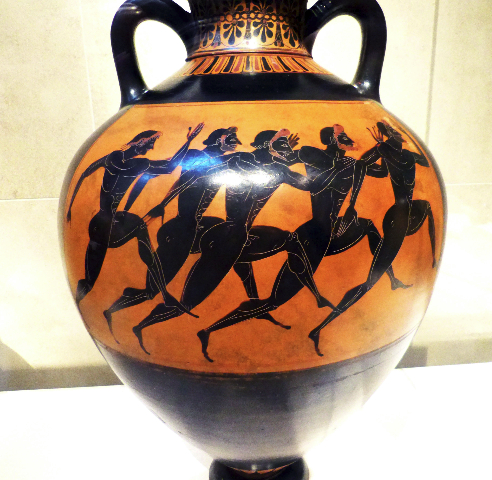

The overall look is derived from the flat, profile images of painted, black figure, Greek pots. In the accompanying slide show I have included a Greek pot of athletes from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While these are aesthetic reference points the artist has provided vividly gut-wrenching vignettes of battle scenes, boat people with their belongings, and the barbed wire of refugee camps.

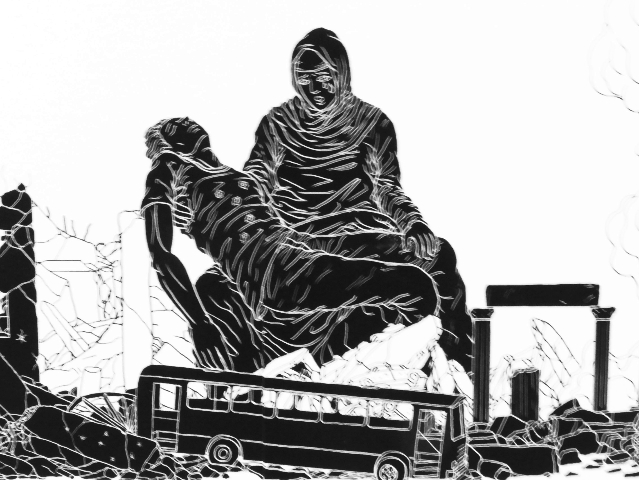

We even found a detail referencing the Pieta of Michelangeo in the collection of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome.

What makes the work of Wewei unique and compelling is that he always finds the fine line and edge between social and political narratves, documentation, agit prop that avoids slipping into overstatement and polemical bathos.

Typically, his projects provide massive amounts of information, more than we can possibly absorb, and then allows us to form our own conclusions.

What most interests me is the broad sweep of his work which conflates information and ispiration, ancient and contemporary, East and West.

He encourages us to think with him as a citizen of the world.

The work makes us look closely into our own prejudices and phobias.

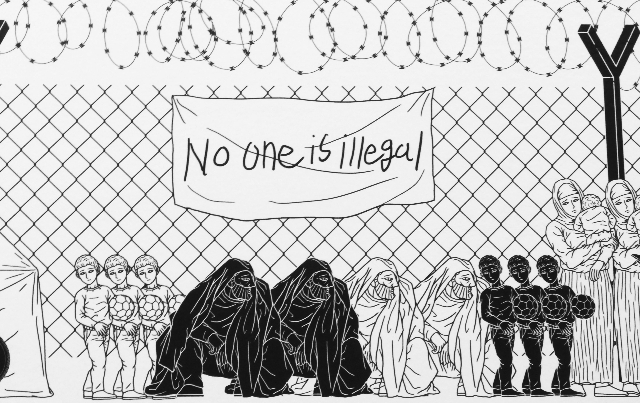

There is an image of downtrodden Syrian women and heir sons holding soccer balls in a putrid camp. On the fence behind them is a sign that proclaims “No One Is Illegal.”

Other than indigenous people, who were slaughtered, all of us are immigrants. I am proud to say that my Sicilian grandfather was an undocumented alien. He slipped over the side and never had the indignity of being stamped a WOP at Ellis Island. On Mom’s side there was the IRA.

Power to the People and Give Peace a Chance.

Link to coverage of Laundromat at Jeffrey Deitch.