Zelda Fitzgerald in P.H. Lin Play

Lost Generation Icon Remains Missing

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 13, 2012

Zelda at the Oasis

By P. H. Lin

Directed by Andy Sandberg

With Edwin Cahill and Gardner Reed

Set designer, Colin McGurk; Costume design Dustin Cross; Lighting, Grant Yeager; Sound design, Daniel Melnick, Choreography, Elisabetta Spuria; General Manager, Jessimeg Productions; Production Stage Manager, Shelby Taylor Love; Casting, Michael Cassara, CSA; Press Representative, Susan Schulman.

St. Luke’s Theatre

308 West 46th Street

Friday at 5 PM, Tuesday at 7 PM, Sundays at 7 PM. Through December.

212 239-6200

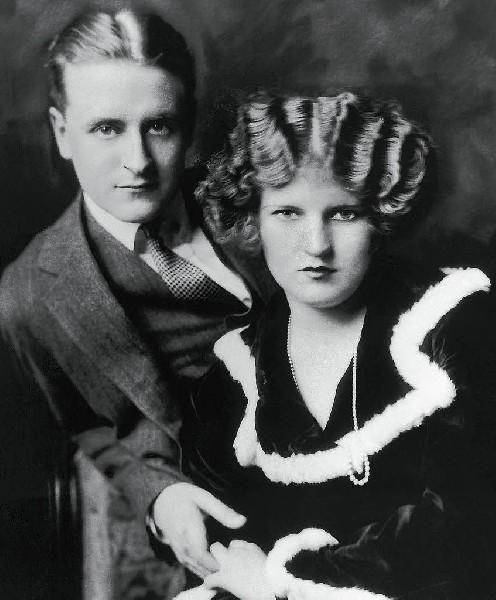

Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald (July 24, 1900 – March 10, 1948) was the wife and muse of the author F. Scott Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940) who enjoyed great success during the Jazz Age of the 1920s which he helped to define with the enduring novel The Great Gatsby.

They were the heart and soul of the Lost Generation of expatriates that enjoyed the more affordable and liberated bohemian life of Paris. Zelda was the life of the party and matched wits with Scott’s literary buddies including Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, the eclectic Gerald Murphy and his stunning wife Sarah, the ballet impresario Serge Diaghilev and his set designer (Parade) Pablo Picasso.

While brilliant, witty and gifted it was a fast crowd to run with. It could be brutal and bruising to be the arm candy of a famous writer. Or one of the wives whom Stein charged her companion, Alice B. Toklas, to round up and keep in the kitchen during their salons while she smoked cigars and talked shop with the boys. Hemingway wrote about Stein savagely in A Moveable Feast but a summary of Zelda’s slights and resentments have not come down verbatim.

Although we have the excellent Nancy Mitford biography Zelda and her own thin and sad attempt at a novel Save Me the Waltz. It reads remarkably as a kind of earlier take on a woman disintegrating so effectively set down in The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath.

The conventional feminist revisionist take on Zelda is that her words and ideas (stolen from letters and diaries) are what inspired the prose of Fitzgerald. Particularly the semi autobiographic characters Nicole and Dick Diver in his epic and complex Tender is the Night.

The strongest rebuttal to that absurd argument is to read Zelda’s book. It is poignant and has glimpses of literary promise but little or no firm evidence that her literary skill was on a par with his.

The book chronicles her brave but frustrated attempt to take up dance in her mid twenties. She worked at it ferociously and arguably found her own artistic identity but it led to neglect as a mother of a daughter Scottie and the beginning of the end of her estrangement from her husband.

It is the 1930s and Zelda has fallen on hard times when we find her inebriated at closing time in the ambitious but flawed play Zelda at the Oasis by P. H. Lin having its premiere at St. Luke’s Theatre in New York through the end of December.

The bartender (Edwin Cahill), who also is the resident singer songwriter of The Oasis, just wants to say goodnight to his last customer (Gardner Reed). Tauntingly, she inquires, do you know who I am?

Apparently not. This provides a clichéd theatrical device of telling who she is in more detail than we really need or care to know. It is a thin wire hanger on which to hang the dirty laundry of the once glittering jazz age which has now devolved into the off key maelstrom of the Great Depression.

Although she proudly proclaims that the term flapper was essential named for her, by the 1930s, the bathtub gin has run dry and, frankly my dear, nobody gives a damn.

While Zelda remains in character through what proves to be a tedious and rocky one act play, Cahill assumes a number of personae, with varying degrees of success. He is most convincing as the bartender who wants to close and keep an appointment with a singer who may use his material and help to launch his career. But with endless exits, entrances and changes of accent he interacts with her as Fitzgerald, Hemingway and two drag bits as her mother and most ridiculously as her Russian ballet mistress.

The evening grew ever more tedious but most exasperatingly when Reed frequently and disdainfully referred to the barkeep with mocking affection as “jellybean.” Had he been black she probably would have called him “boy.”

Zelda is indeed one of the compelling and most tragic icons of a complex era. There is a great play, novel, or film lurking on the horizon. But this is not it. What we have is an awkward patchwork of vignettes offering no connection or real insight. It just adds to the long list of other Zelda failures. Which is, perhaps, too emblematic of a creature of the Lost Generation.

The demise of Scott is no less compelling or dramatic. The difference is that Scott did indeed leave an enormous literary legacy. Although, by the 1930s, in keeping with the Great Depression, it was worth ten cents or less on the dollar.

The difference is that Scott was great while the tragedy of Zelda was that her similar ambition has left nothing tangible other than her artistic failure.

Whom the Gods love die young.

Scott died as the result of the Irish suicide of alcoholism at 44. At the time he was a washed up screen writer in Hollywood.

At the end of Lin’s play Zelda is headed back to the sanctity of a mental hospital. She would check in and out frequently. On March 10, 1948 she was killed in a fire at the Highland Hospital. She was 48 at the time.

Decades later they continue to inspire and fascinate us. Hindsight brings compassion and insight to these brilliant and tragic figures. It is a legacy that we will be inspired to return to again and again.