De Kooning at MoMA Through January 9

Soul on Ice

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 07, 2011

At the funeral of Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) who died in a car accident/ suicide his friend and rival, Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) famously remarked “Pollock broke the ice.”

It was a reference to his singular expansion beyond easel painting, rolling out long swatches of canvas on the studio floor. Pollock attacked the surface from all sides in a kind of choreography pouring and flinging commercial paint and enamel. It created a basically inimitable style and singular position at the apogee of the New York School.

This occurred during that window of time that Irving Sandler has dubbed The Triumph of American art. Assumingly vanquishing the deflated post war School of Paris. Harold Rosenberg dubbed it American Type Painting and Action Painting. Marxist art historian Serge Guilbaut formulated a disputed thesis of how, with the help of the Department of State and globally circulated exhibitions, New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art.

If Pollock broke the ice, arguably, de Kooning was the iceman.

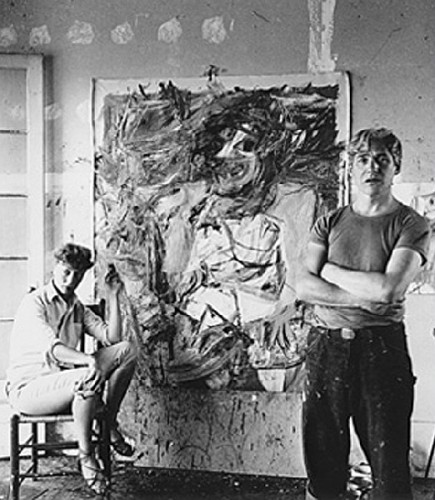

In a sprawling, once in a lifetime, galvanic and cathartic exhibition de Kooning : a Restrospetive with some 200 works on view at the Museum of Modern Art through January 9, we absorb the notion that however radical in some aspects of the work, the Dutch born artist never wavered from a fixation on easel painting (some quite large). The figure was a paradigm that he constantly assaulted in an arc from distorted representation through abstraction.

Comparing the twin towers of post war American art, Pollock and de Kooning, they were the leaders of seemingly dichotomized party lines and philosophies that demarked the fault line of an American avant-garde. Pollock, who grew up in Cody, Wyoming and studied with the Kansas regionalist Thomas Hart Benton, evolved into vast abstracted, all over canvases that might be regarded as extensions of the traditions of American landscape painting.

The Dutch born de Kooning, while regarded as a leader of American art, retained the soul of a European absorbing the American experience. This he shared with other foreign born masters of the New York School, Mark Rothko ( 1903-1970) Hans Hofmann (1880-1966) and Arshile Gorky (1902-1948).

These artists created with such sublime emotional intensity that they evoke wobbly, weak kneed, cathartic, heart thumping, vertigo inducing responses to large surveys of their work.

There are a few times in my life when I have been stopped dead in my tracks, rendered temporarily mute and deranged, transported briefly to that land from which no traveler returns, when contemplating works of art. A short list of such encounters would be time spent with the Venus of Willendorf in Vienna, the Sistine Chapel in Rome, Goya’s Black Paintings in the Prado, an Ad Reinhardt retrospective in LA, the Rothko Chapel in Houston, and more recently staggering through the de Kooning exhibition in New York.

The latter experience was so disorienting and emotionally overwhelming that I had to find a bench to sit and recoup enough to move on. It was like waking up the morning after sick and hung over with the woman you met during last call. Perhaps it would take Dostoyevsky, Sartre or Camus to deconstruct the nuances of the experience.

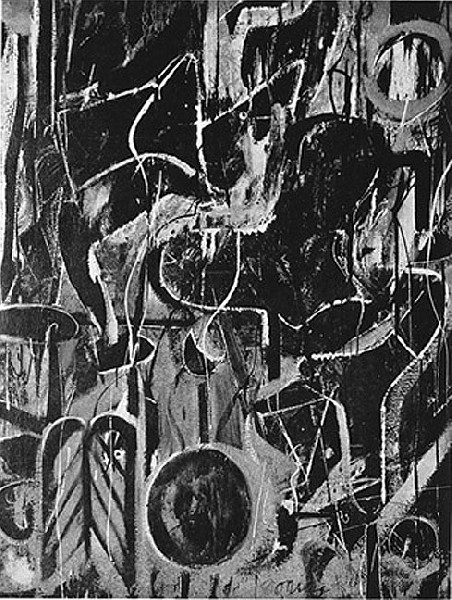

There was far more pain than pleasure involved in absorbing a sweeping survey of such a tormented and possessed individual. Many of the works were so dark, twisted and inscrutable that they seemed like they were created in a pact with the devil. Like Goya’s Black Paintings they require a Dantesque descent into the Inferno to comprehend the root and essence of the work. It channels Brando in the final scenes of Apocalypse Now with his last breath whispering “The horror, the horror.”

When individuals put so much of their heart and soul into the work it renders moot the notion of a normal life. There is always the temptation of scooting down the rabbit hole of biography and anecdote, a bit of “eat me” “drink me” along the way, as a template for unraveling the “meaning” of the work. In that regard we strongly recommend the Mark Stevens biography which conflates the facts and chronology of the life with insights to the work. It is the approach taken by John Richardson with great success in dealing with the life and work of Pablo Picasso.

The massive catalogue that accompanies the MoMA exhibition, other than its copious illustrations, proves to be useless. Starting with an essay by the curator John Elderfield it is a compilation of tedious writing by academics. The notion of explaining the work within the framework of conventional art history is unproductive as a companion and guide to take us through the exhibition.

For that we would need to conjure up the restive shade of Virgil to lead us through the circles from beginning to end that comprise the spiraling horror of the artist’s life and work. Not that I claim to offer a richer and better understanding. That would be like trying to deconstruct someone else’s acid trip. It’s hard enough to understand our own experiments with supranaturural phenomena.

Finding space on a bench I was perpendicular to a wall of mid period, large, abstracted paintings. In large retrospectives of an artist’s work it is inevitable that the experience is uneven. The challenge for an observer is to separate works that succeed in their intentions from those that do not. This is particularly difficult when contemplating very similar works from a narrow time frame or theme within the oeuvre.

One approach to this sorting out process is a kind of self imposed game. If you were a collector or curator which one of a group of a dozen or so would you buy? Of course with a ‘good eye’ we strive to find the best work.

This was particularly fascinating when standing before a wall of Women. They were all of the same dimensions and from a roughly equal time frame. The fascinating point was that one was a masterpiece, an icon of mid 20th century art, another lagged not far behind, and the rest ranged from mediocre to utter crap.

I couldn’t help myself imposing the game on a couple which seemed to be intently observing the series of Women. It visibly changed the experience for them. After some concentrated effort they had the right answer “Woman 1” from MoMA. Right on. The runner up is the Whitney’s “Woman on a Bicycle” with the cat’s head, feline eyes and two sets of snarling teeth the better to vagina dentata you my dear.

Of course the contemplation of the ferociously distorted and sublimely executed vicious harpies begs the obvious question of what the artist thought of women. Volumes have been written about that conundrum. But, ultimately, does it matter? Whatever his true feelings de Kooning paid for those works with his blood, guts and sanity. Little wonder that he drank himself into the gutter. Or, having kicked on advice of doctors and the pleadings of loved ones, spent his final years fighting dementia.

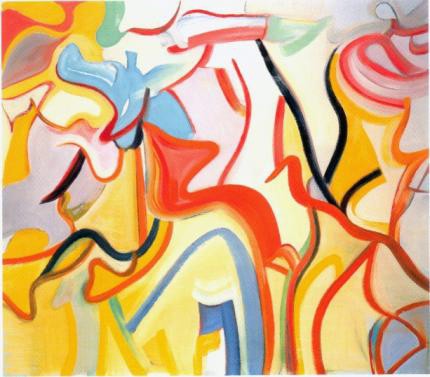

The works produced when he was non compis mentis are a puzzle and enigma. It is questionable how many of their aesthetic decisions were his and to what extent that of assistants. The other moral part of the dilemma is their staggering monetary value. Does a study of the work of this late period comprise art history or the investigation of criminal fraud?

Perhaps the greatest revelations and insights to the exhibition were provided by the early works. They are, indeed, quite Dutch in their meticulous, traditional rendering. There is an early, small, pencil portrait of the artist’s wife, the painter Elaine. It is a perfect gem drawn with pristine precision. Like Picasso he was a well schooled academic before he plunged into decades of unfettered experimentation.

When such large and ambitious surveys reveal the Achilles heel of uninspired, routine works, and fallow periods, of which there is abundant evidence here, the critical carp is to demand some curatorial pruning. There has been a chorus of that in response to this MoMA show.

But it is a wrong and stupid notion. Rather than edit an exhibition and accordingly “strengthen it” I prefer the approach that I foisted onto perfect strangers. Leave it to the viewer to cull the good and bad works. Indeed it requires the experience of the artist’s mistakes and pratfalls the better to appreciate the numerous masterpieces in the oeuvre.

Often there is that thing called life that interferes with the creative process. Nobody, not even great artists like de Kooning, hit a home run with every swing of the brush.

Even curators make mistakes. I was furious when Bill Seitz swapped an early Woman for a more mainstream, mid career de Kooning abstraction for the Rose Art Museum. As with sports often the best trades are the ones not made.

Parked on the bench I was struggling to overcome the aesthetic nausea of imbibing all of that visual angst. Next to me two women, New Yorkers who reeked of fashion and phony sophistication, were comparing their trips to Niagra Falls.

Angrily I turned to them and said “Excuse me. Can you focus on the art?” They were shocked and offended responding that it’s a free country and a museum is not a church. “No” I replied “It is a cathedral and de Kooning is a God. Why don’t you go have lunch and talk about your travels? Why do you even bother to come to a museum?”

With indignation they responded “Because we’re artists.”

To which I responded “Exactly.”

Then a friendly Haitian guard came over and politely asked me not to feed the animals.

Women who lunch. New York dames.

Small wonder that de Kooning savaged them on canvas.

Bravo.