Izhar Patkin: The Wandering Veil

Vast Installation at Mass MoCA on View for a Year

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 05, 2013

Izhar Patkin: The Wandering Veil

Kashmiri-American Poet Agha Shahid Ali wrote "The Veiled Suite" specifically for his collaboration with Izhar Patkin.

Co-organized by MASS MoCA, The Wandering Veil travels to North Adams from the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Tefen Open Museum in Israel, where it premiered last year.

Mass MoCA

Opening Saturday, December 7, 2013

Reception: Saturday, January 18, 2014, 3-5pm

When the 17 acre former Arnold Printworks/ Sprague Electric was transformed into Mass MoCA the most dramatic change occured in Building Five. Built in the 19th century, flanking walls with enormous vertical windows were essential for providing natural light during sunrise to sunset work days that preceded electric illumination.

The decision was made to remove the second of two floors. This resulted in a vast, vaulted, basilica-like space one of the grandest to display contemporary art in North America. The others are Chinati Foundation in Marfa, Texas and Dia Beacon in upstate New York.

The long gallery represents a daunting challenge to the dozen or so artists who have been hosted for year long exhibitions. The greatest aesthetic aspect is the space itself. The artist is presented the option of emphasizing that openness or treating it as a gallery in which to install their work. It is a matter of the container vs. the contained. The glass is either half empty or half full.

By now we have seen notable examples of both approaches.

For this latest project the impression is half full. Entering the gallery there is no sense of a grand vista. Walking through the space we find a pattern of square rooms that we enter to view four each, hanging veils or curtained narrative paintings.

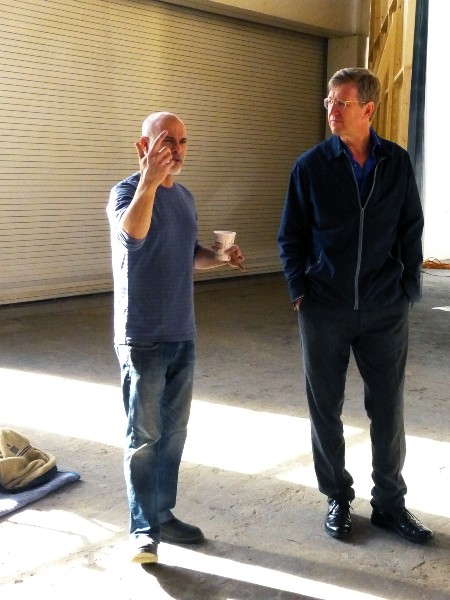

Following a press conference at Mass MoCA announcing programming for winter/ spring Joe Thompson, the director of Mass MoCA, led a small group through the exhibition Izhar Patkin: The Wandering Veil which opens on Saturday. The reception with the artist is scheduled for January 18.

Earlier he had said "He doesn't stick to a single format, or style, or media. He is restless and reflexively experimental which is difficult for the art market to grapple with."

The artist was working on the final stages of the installation disrupted by an informal intervention.

Not knowing how much time we would have, or if we would be allowed to tour the work in progress, I started taking photographs of the artist.

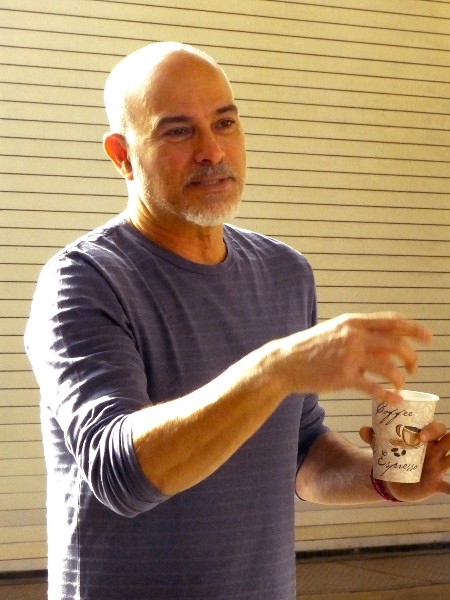

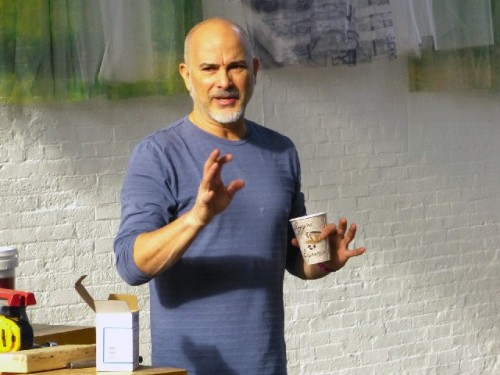

He responded with the deadpan humor and irony which pervades the work itself. Disarmingly, he told me “I’m unprepared and haven’t done my hair or makeup.”

The joke was that the artist is bald.

It was also a signifier of how to approach him and the work.

His career took off when several of the black veil paintings were included in the 1987 Whitney Biennial where they were a critical sensation. They were later acquired by the Museum of Modern Art. The artist has commented that they don't understand them. It is intuitive to respond to their gossamer beauty but typically multivalent and obfuscating when probing their unique iconography.

At the time he was in the stable of Holly Solomon who showed prominent artists of the then trendy Pattern and Decoration movement. Which he denies that he was a part of. Although his paintings were viewed as "decorative" he says that they were about narrative content which was not an aspect of that movement. He explains that P&D was a response to the fading movement of conceptualism and not where he was coming from.

The ebb and flow of contemporary art movements was a phenomenon that the artist was formerly a part of but opted to walk away from. For many artists inclusion in the Whitney Biennial provides a spurt of media and curatorial attention. Only a handful of artists manage to sustain ongoing careers while the majority constitute eventual triva questions.

During the morning press conference Thompson informed us that the work is full of jokes and visual puns. To illustrate this he projected a detail of a painting on a wall of Amish barn boards.

In a crudely painted reference to the visual trickery of Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1526 or 1527 – July 11, 1593) a bowl of fruit formed a comical face. Thompson pointed out that next to this image was a key dangling from a nail. The key was an illusion in the technique of trompe l’oeil while the nail, and its cast shadow, was not.

We located the key but the nail was missing and yet to be installed.

This vector into the intentionality of the artist was arguably light and whimsical but the complex, multi layered project, proved to be anything but.

There are as many approaches to understanding this exhibition as there are visitors.

Most of those who tour Building Five, about two football fields in length, will interact with the visual pleasure of rooms displaying large, painted curtains or veils on each wall.

When Patkin and curator Susan Cross discussed text for wall labels she would suggest something. At first agreeing, he would then propose something different.

I found that out for myself.

Thompson and the artist were engaging in an overview when I asked specific questions. I asked about the eclecticism which Thompson had brought up. How and why he pursues so many different modes and tangents from modeling and casting sculpture, to working with glass, porcelain, metal, wood, painting gossamer, illusionistic, ghostly images on curtains or veils, and the series of 100 encaustic screen paintings '"Gardens of Global Cities" which reference carpet patterns.

In response to questioning the eclectic nature of the work he sharply responded “I don’t suffer from ADD. I am entirely focused.”

Cool. But now engaged and challenged he discussed the abountness of the screen paintings which resemble “Oriental carpets. I know you’re not supposed to talk about Oriental carpets. But…”

Were they inspired by or copied from actual carpets?

"Not really."

Then, how are they painted? With a brush?

"No, with my hands. I push the hot wax through the screens."

Now in full stride he titubated through a bit of theoretical moon walking.

The discussion reached back to his years in Israel. There was little contemporary work to look at or be inspired by. In art school instructors engaged in discussions of Greenbergian formalism and the arguments of the integrity of the picture plane, flatness, and non objective abstraction. That entailed the notion of taking God and religion out of art and eliminating narrative. For the most part Abstract Expressionism removed iconography from art he implied.

I asked him about the Rothko Chapel. Other than a furtive glance he brushed that off. Had we pursued it further we might have discussed the Elegies of Motherwell, The Stations of the Cross of Barnett Newman, Jungian imagery in Pollock, Women in deKooning, Northwest Indian influences in Peter Busa. It is perhaps best that Patkin deflected from his Wittgenstein based arguments that the abstract work of art be judged only within its own terms of creation.

He detoured back into how the carpet paintings served as a way of coming back to issues that Greenberg found to be anathema. The screen as support in his work represents the ultimate instance of flatness, indeed ephemeral and transparent, with the pigment pushed through. He was asked to show us the back.

Flipping one over we saw the smooth smear of flatness where the paint had been smushed through the screen producing a richly colored texture on the other side.

Looking about he commented on how the encaustic paintings might be seen in the context of the New York School. A composition divided into a series of hovering, stacked rectangles could be seen as “A Rothko.” In another work the pinkish colors and all over textures suggested a painting by the surrealist Masson.

Examining one work he pointed out a tree of life pattern treated differently on either side of the central trunk and branches. He touched on, but did not go deeply into, the Jewish and Islamic traditions of the taboo against the graven image. It is something, as a secular Jew and avowed atheist, that he both respects and defies.

In the ancient taboo against figuration (with periods and notable exceptions) Jewish and Islamic artists became masters of, you guessed it, pattern and decoration. Little wonder that this is a difficult issue for him and why he insists on an ambivalence about deity.

It was intriguing and I would have loved to have followed him deeper down the rabbit hole but he sensed that he had lost his audience. He was speaking to a gathering of journalists not philosophers and art historians.

Perhaps this is an aspect of what happened to the artist when, after early success, he dropped out of the art world for over a decade. During a relatively brief time span he lost what he descibes as "eight of the ten most important people in my life" including his father, art dealer Holly Solomon, and the poet collaborator Agha Shahid Ali.

One of the veils depicts his father seated in front of the World Trade Center just days before 9/11. In a videotaped interview David Ross, museum director, curator and critic, brought up 9/11. (They will meet for a public dialogue in the museum.) The response was astonishing. As an Israeli (he left in 1977) he said that “I’m used to that.” With respect he observed that 9/11 was just America catching up with what was going on all over the world. One of his closest friends in Israel was killed by terrorists and he described multiple bombings in his native village.

For a time he was so traumatized by personal losses, particularly a father he was so close to, that making art, and playing the art world game, just didn’t make sense to him.

The current exhibition resulted from a close relationship with Kashmiri-American Poet Agha Shahid Ali who wrote "The Veiled Suite."

As a secular, non believing Jew the veils are where he connects in a mysterious and ephemeral manner with a Muslim poet. The metaphors of mourning, loss and memory pervade the series. He told Ross how the Islamic poetry of his collaborator is intended to move us to tears. He is interested in how different cultures and religions, those of friends as well as enemies, respond to common humanistic conundrums. How we kill and hate in the name of a God that loves us.

There is a potent substratum of the work which explores what happens when the secular Zionists who formed Israel are now subsumed in the culture ever more dominated by fundamentalists. Early on it was advanced that to criticize Israel is an act of anti Semitism. It is a mordant argument that transformed the philosopher Hannah Arendt from Zionist to pariah.

This is dangerous territory to explore as Patkin does in work that is so rich in narrative. The emotionally embedded work, however, lacks a deflective shield of irony which is the trope of post modernism. In their dialogue Ross suggests that consequently the work might be viewed harshly by art critics or the followers of militant rabbis. Ross, however, treads lightly and does not state his own position on Zionism.

Significantly, Ross probed the motivation behind leaving Israel in 1977. It implied conflict that might make him a refugee. Patkin gave a deadpan response to the loaded qustion.

A close reading of this rich and complex exhibition suggests that it is somewhat quixotic.

Perhaps that is why we encounter a sculpture of Don Quixote as we descend the stairs and enter the gallery. The artist commented that it is quite deliberate that the horse’s ass faces us as a “greeting.”

The life sized sculpture reveals the hero of the Cervantes novel about the last gasp of delusional medieval chivalry gazing at his reflection in the mirror. Patkin discussed the multiple layering in the novel where the deranged character constantly studies his reflection and image. At times he addresses the reader directly as narrator of his own heroic saga. His elaborately staged actions convey a self absorbed utter madness. There is the ongoing reality check of his deadpan servant on a donkey Sancho Panza. As with Lear, and his Fool, Quixote's companion, Panza, is the voice of reason.

The motif of the mirror and reflections thread through the exhibition. One of the curtains, in this case polychromed, deconstructs the use of the mirror in Las Meninas by Velasquez.

This is art in the mannerist realm of artifice or artificiality. One might say artsy art.

Patkin revealed one of his tricks. He told us that he sculpted the horse, from a large block of clay, to be just under normal scale. As a model for Quixote he enlisted the help of his friend the architecture critic for the New York Times. He then made a life cast in wax.

In hot water the wax cast was pulled to stretch to a larger than life figure. That results in an overblown Quixote on a shrunken steed.

He explained that shifts of scale are an important element in the illusions of his work.

It seems that his friend from the Times had misgiving about being depicted as Don Quixote. That’s too close for comfort for a critic. So the artist agreed to keep secret the identity.

That changed when the piece became famous through inclusion in the Whitney Biennial.

At which point the Times critic told the artist that he had never asked to be anonymous.

How quixotic.

Video URL for interview with David Ross.

Video URL for Kashmiri-American Poet Agha Shahid Ali.

Video Url for Caetano Veloso reads Agha Shahid Ali's translation of Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish's work, "Violins."

Link to New York Times interview.

Dialogue with David Ross at Mass MoCA.