Gloucester Modernist Umberto Romano

At Annex of Cape Ann Museum

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 04, 2024

The modernist Umberto Romano (1906-1982) is the subject of a retrospective, curated by Martha Oaks, at the annex of the Cape Ann museum through December 29, 2024. The main museum is closed for renovation. The exhibition is free to the public in the 12,000 square foot Janet & William Ellery James Center, which was completed in 2020. It includes 2,000 square feet of flexible exhibition and community programming space.

The spectacular gallery is more than adequate for a much deserved overview of a fascinating artist who, though now obscure, enjoyed a significant career with a thirty year presence on Cape Ann. Discouraged by the lack of support; in 1965 he sold his property and decamped to the more vibrant Provincetown community. That move signified the last gasp of modernism in Gloucester until a resurgence in recent years.

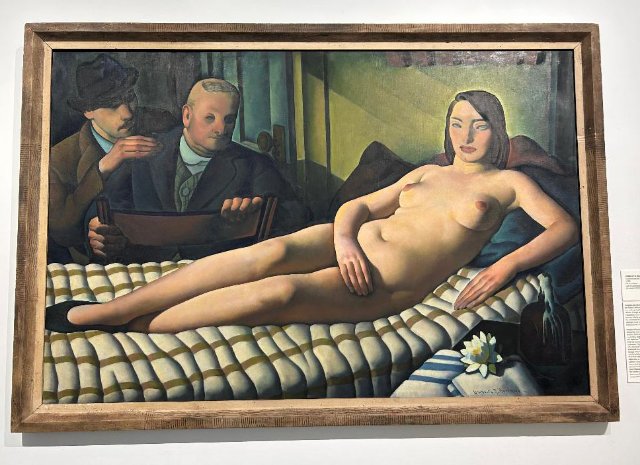

The centerpiece of the current installation is “Susanna and the Elders” a work from 1928 which is displayed beneath the banner for the exhibition. It’s a singularly galvanic painting that I have long admired in the museum’s permanent collection. With several other works it evoked curiosity about the artist’s career and status in a community which, by his prime, had lost its most progressive artists and was on a downward spin as a matrix for reactionary representation and maritime kitsch. It is little wonder that Romano eventually felt isolated enough to move on.

Susanna was a popular subject for artists from the Renaissance on as it provided the opportunity to convey smarmy voyeurism with lusty men spying on a naked female. In this version there are just two peeping toms the second and less prominent of whom is the artist himself. The rendering in a classical style is typical of the era of the American scene and regionalism. With an invisible brushstroke the figure is smooth, sausage-like and pneumatic. With slits for eyes she is composed and seemingly indifferent to the vexing and rapacious male gaze. This work recalls artists of a stylized manner in particular Grant Wood, George Bellows or Guy Pène du Bois. There is a connection back to the Baroque artist Caravaggio and his followers the Utrech school of candlelight painters. These latter influences are likely derived from a prize to study in Europe.

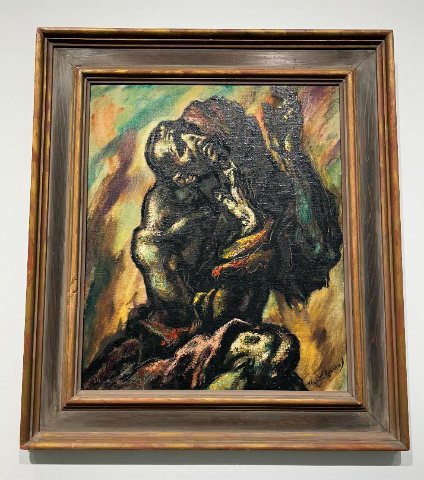

Certainly this work and others from the 1920s and 1930s are among his most engaging. His later ventures into dark, and at times, melodramatic expressionism are erratic at best.

The artist was born in 1905 at Bracigliano near Salerno, Italy. The family with eight children immigrated to Springfield, Massachusetts in 1914. His early art education was at the George Walter Smith Museum School in Springfield. At 16 he enrolled in the National Academy of Design in New York City. There he won the Pulitzer Prize for a year of study in Italy. By 1928 he showed at Rehn Gallery, which had Gloucester roots, and was given a solo show in New York the following year. That led to being included in exhibitions at the Carnegie Institute, Cincinnati Art Museum, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and Art Institute of Chicago. He was shown in the first Biennial of the Whitney Museum of American Art.

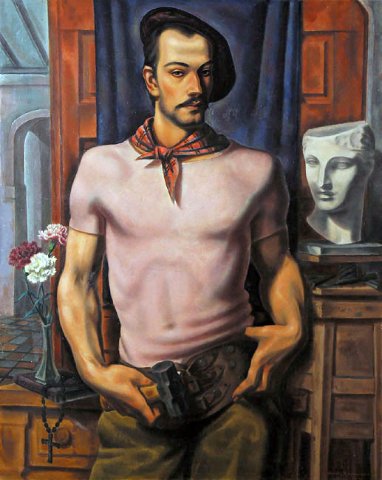

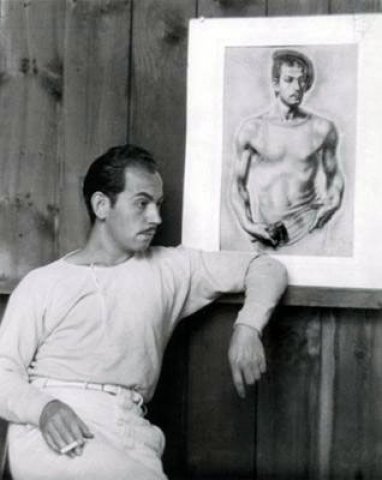

With a bandana and beret he strikes a macho pose for “Psyche and the Sculptor” from the 1930s. He holds a hammer in the vicinity of his groin. To the right is a marble bust of the god which he has carved.

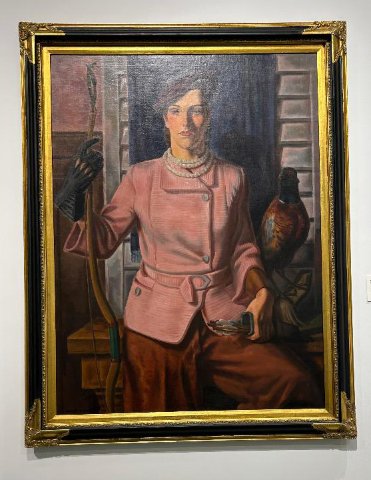

In the art deco inflected manner of the period his first wife is shown with dress of the era as the mythical “Diana” goddess of the hunt. With an archer’s glove she holds an unstrung bow in one hand and a quiver of arrows in the other. Her posture and gaze are frontal and somewhat menacing. This is a woman who means business. A triple strand of pearls is out of sync for a woman of action. Romano’s goddess is less a nymph of the forest than a sophisticated lady of status and means.

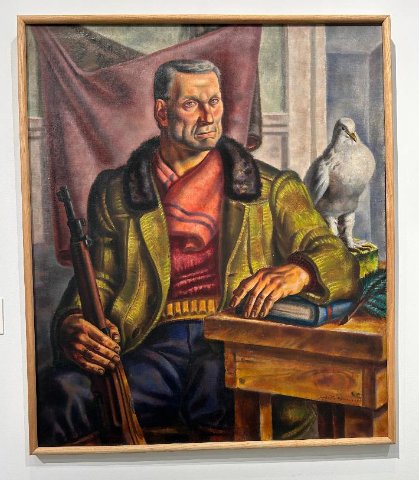

Another strong work of this period is the portrait “Gamekeeper.” The man with chiseled handsome features is seated with his head gazing to the side. He is dressed for outdoor work with a gun in one hand and his other arm resting on a stack of books on a table. There is a stuffed bird as signifier of his trade. The artist conveys this man with palpable respect.

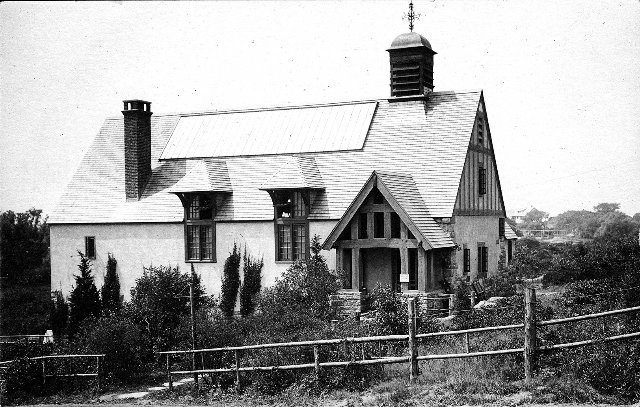

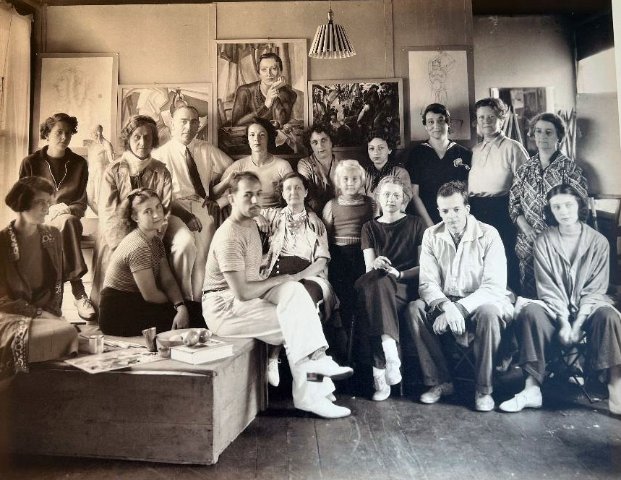

It’s possible that they may have visited earlier but the Romanos came to Gloucester in 1933 and with a few studio moves eventually established roots. In various locations he founded the Romano School of Art. Initially he taught in a schooner docked in Rocky Neck. In 1938 the Romanos purchased the legendary Gallery-on-the-Moors which was built in 1916 (designed by Ralph Adams Cram) for the collectors and gallerists, Emmeline and William E. Atwood. They showed Gloucester’s early modernists. The space housed their school, a gallery, and stage for a variety of performances. It was a great loss for the community when Umberto and a second wife sold the property and left Gloucester.

By 1940 his marriage ended with the collateral result of loss of his position as director of the Worcester Art Museum School. At the time ill health was given as the reason for his resignation. As it was for all Americans the war years of the 1940s involved hardship and aesthetic change. The work grew dark, fragmented and depressive. A representative work “Cargo” (not in this exhibition) depicted a survivor of a merchant marine sunk by a u-boat. The sprawling figure seen in foreshortening is nude with drapery over his genitals. An arm is clutched around his anguished face. Thematically, this war inspired piece links to the monumental “Raft of the Medusa” by Gericault.

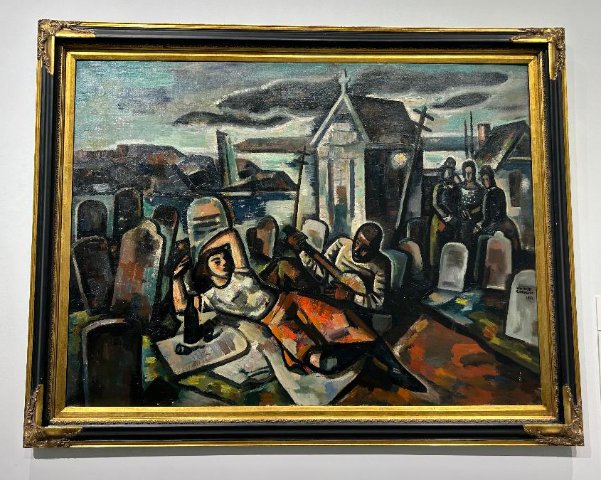

Even in the 1930s, however, there was an edge to the work in, for example, “New England Tragedy,” 1934. The dark, expressionist painting of a picnic has a woman stretched out in a lascivious manner with her arms clasped behind her head as though welcoming a lover. He is seated on the ground next to her strumming a guitar. This evocation of Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe is incongruously set among grave stones. There are women to the side who witness this lewdness. It’s an odd but engaging painting.

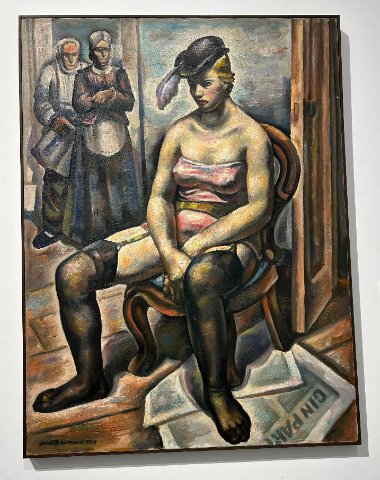

The most curious painting in the exhibition is “American Breadwinner” undated but likely from the 1930s. A woman in her underwear with garters and stockings is slumped into a chair. Her arms are folded concealing but drawing attention to her genitals. She wears what the catalog notes as an Empress Eugenie hat, a form of derby with a feather draping forward. What may be her parents are off to the side. Plausibly they may be the beneficiaries of her sex work during the Great Depression.

Romano’s floozy evokes those of Reginald Marsh. I am more specifically reminded of the better work of Chicago’s Ivan Le Lorraine Albright. With lack of more curatorial elaboration this interesting picture appears to be a one off.

The catalog essay of Oaks is less than through critical analysis and assessment of the oeuvre. The lack of depth discourages drawing broad assumptions about the work. The stylistic shifts of paintings on view raise unanswered questions. The exhibition drew on the museum’s substantial donations from the Umberto and Clorinda Romano Foundation but was less than definitive in not borrowing key works from other museums and collections. We came away enticed but hungry for deeper understanding of an intriguing artist and his work.

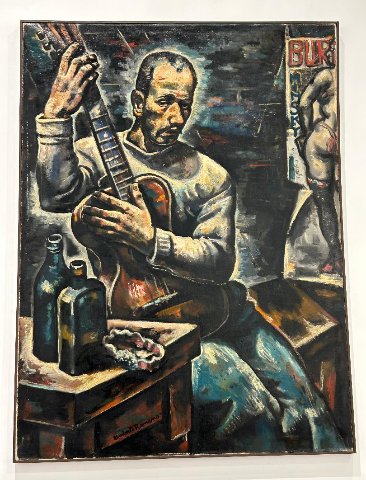

Another painting that suggests Albright is “Man Sings of Man” 1930s. In a somber mood, perhaps a self portrait, the subject holds a guitar vertically. In the background is a slice of the rear of a stripper under a shortened banner that reads “Bur.” Morosely, on the table next to him are two empty liquor bottles and a garter belt. The picture is a curious pity party. It’s difficult to feel empathy for the protagonist. We need more information to determine whether the work is a reflection of the artist’s experience.

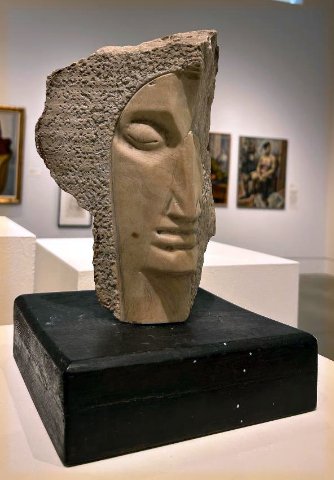

There were examples of sculpture but what we viewed is uncompelling. The jury is still out on this aspect of the oeuvre. There is an anguished horse’s head in hammered bronze. Examples of carved stone heads compare to those of Modigliani.

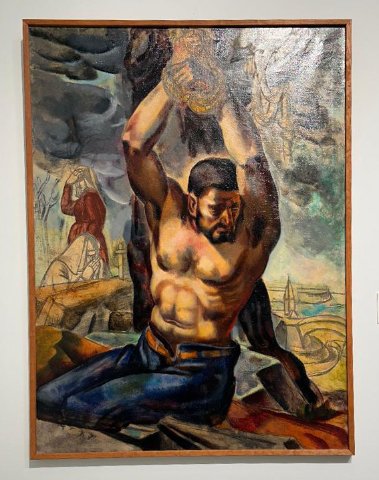

The works from the 1940s were erratic. From 1946 “Let My People Go” was a misstep into the domain of social justice. He was out of depth and melodramatic in treating the subject of slavery. This is an aspect of the work that needs further research. “Ecce Homo” (1949) is somewhat more successful. A well conditioned man, stripped to the waist in jeans has his hands bound above him. It illustrates the words of Pontius Pilot “Behold the Man” who washed his hands of the condemned Christ.

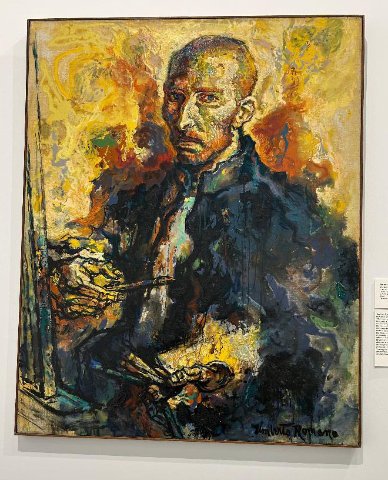

After leaving Gloucester Romano undertook two ambitious projects; The Great Man Series and Glass Box Series. The latter was inspired by the trial and execution of Adolph Eichmann. From the Great Men (of which there are some 40 examples) CAM has included “Homage to Rembrandt” and “Van Gogh.” Neither work, more caricatured than insightful, is particularly effective.

The highlights of this exhibition are stunning. Arguably they are enough to offset troubling and less successful works. The artist deserves further study in order better to understand the impact that his personal life, failed marriage, and zeitgeist of America enduring depression and war had on the work. The evidence on view at CAM suggests that he was thrown off course. Other than stating the essential biographical facts the exhibition lacks an art historical approach, Romano’s position in modernism, and impact on the artists of Cape Ann.

The exhibition is accompanied by Umberto Romano, a 42 page illustrated catalog with essay by Martha Oaks. It includes additional images of works not in the exhibition.