Liu Zheng: The Chinese

Exhibition and Acquisition for the Williams College Museum of Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Dec 03, 2008

Liu Zheng: The Chinese

Curated by John Stomberg

The Williams College Museum of Art

Williamstown, Mass.

November 15 through April 26, 2009

http://www.wcma.org/

Liu Zheng: The Chinese

Introduction and Acknowledgements, Christopher Phillips, Essay by Gu Zheng, Interview with the artist by Meg Maggio, Artist Statement, Biography, and Bibliography.. Published, The International Center for Photography, New York and Steidl Publishers, Gottingen, Germany, 142 pages, 2004.

The galvanic, poignant and harrowing exhibition of 120, silver gelatin prints "Liu Zheng: The Chinese" is remarkable and historic on many levels. During a gallery meeting with the exhibition curator and Deputy Director of the Williams College Museum of Art, John Stomberg, he stated that the entire set of images published in the 2004 book had been acquired for the collection.

The process of printing the images had been so excruciating for the artist that he has vowed to abandon the darkroom. The museum, which commissioned the set of prints through the Edward Wachenheim Family Fund, asked the artist to reprint several images and received an emphatic and exasperated refusal. The artist intends to scan the negatives and any further prints from the series will be created digitally.

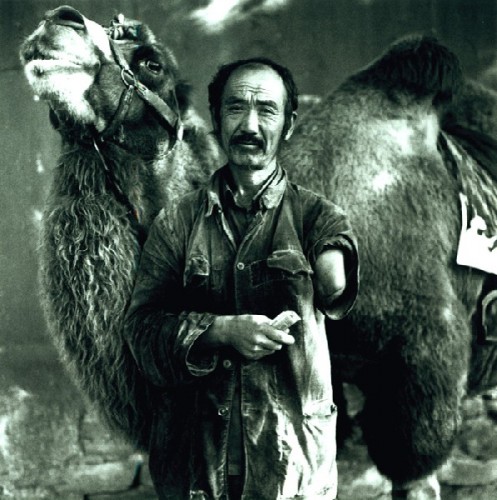

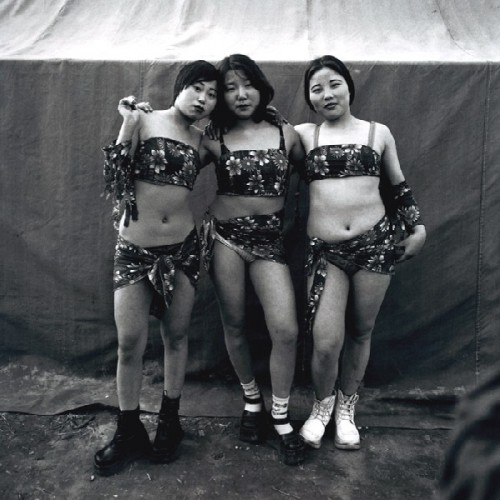

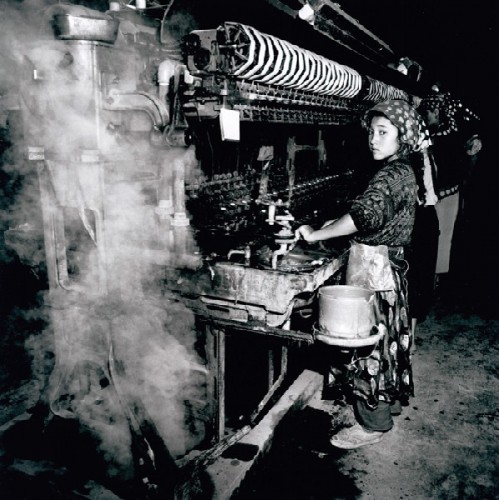

This emotional response from the artist is not surprising based on remarks in the book, published in 2004 by the International Center for Photography and Steidel Publishers, through an interview with Meg Maggio and the artist's statement. The project which was pursued between 1994 and 2001 involved extensive travel in China with limited resources. In general, he traveled for a month, then returned home for a month. He would plan the next trip and scrounge for funds. Not only was the travel grueling but the images reveal a self imposed exploration of the lower depths of death, mental illness, horrific industrial accidents, and the fringes of society including transsexuals, prostitutes, actors, peasants, inmates in prisons, and patients experiencing little or no treatment in the most primitive hospitals.

The work drove the artist to the brink of despair, exhaustion, and human misery. It is a visual catalogue of the kind of travel from which few return to tell the tale. This all occurred during a time of dramatic national transition and change in the era of liberation following the repressive Cultural Revolution. Zheng was a part of the generation of artists who blossomed with the end of artistic repression. But they also navigated a difficult transition between the ironic securities of the former Maoist nationalism into a new and uncertain climate of rapid social and economic change, greed, and a loss of innocence.

During the pursuit of his Odyssey Zheng comments that where initially people were warm and welcoming to strangers they gradually became less accessible and trusting. At first, it was easy to photograph freely but, over time, his potential subjects wanted more information on the motive of the artist and the use of the images. Often this meant that his subjects expected to be paid for their cooperation.

As the images came to be seen in China the response was not always supportive. It was felt that Zheng was creating a deliberately negative and judgmental view of the Chinese. There were critiques of the agenda of the artist. Looking carefully at the images, and reading the artist's statements, one concludes that this was a very personal project and despite its rather grand and sweeping title "The Chinese" is more of a diary than an indictment. The images represent a selection of what interested the artist.

His mother's family had been artists who created traditional scenery for Chinese New year Celebrations. All of that work disappeared during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). His parents, gradually lost everything after the New China (1949) and became destitute peasants. They discouraged his interest in art and Zheng was forced to study engineering. While a student he took an elective course in photography which induced him to drop out of school .He had started, first as a traditional painter, then as a photo journalist, so he knew what was involved with working on assignment. Artists of prior generations were mandated to serve the agit prop needs of the regime; to put a happy face on the worker and the Cultural Revolution. In this project there was the freedom to act independently but also without support, resources and funding. When he quit as a photojournalist, for example, he had to turn in his cameras.

Because of his highly selective methods there were times while traveling that nothing resulted. His approach was not to take a vast number of images and reduce them to the 120 in the resultant book. When he attempted to photograph happy and contented individuals it just didn't work. Much of the horrific drive to record rural funerals, cadavers, and the macabre evolved from experiences in his personal life. The funeral of his grandfather had left a lasting impression on him and a number of images result from that experience. So the resultant images are extensions of his persona. The series might just as aptly haved been titled "Self Portrait" instead of "The Chinese."

Although Zheng, who was born in 1969, spent seven years creating this series it is uncertain whether in any way it gives us a better idea of "The Chinese." It is, at best, a beginning of coming to understand something about the artist and his unique vision. Several years ago, Astrid and I spent an intense week in Shanghai. This brief, first hand encounter produced nothing like the images in the exhibition. We experienced a tiny glimpse of a culture that demands a lifetime of travel and study to comprehend. The topic is so daunting that it threatened to engulf the artist. In a reversal of the usual process of enlightenment, like Dante and Plato before him, he opted to descend into a kind of hell on earth to study the shadows on the wall and the restless movement of shades.

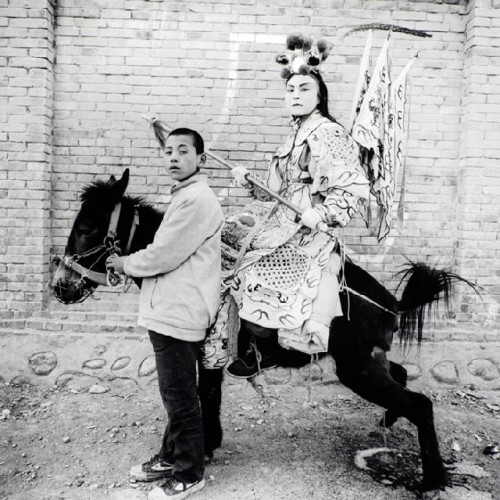

The artist has stated that August Sander and Diane Arbus were inspirations for his work. There is a similar, deadpan drive to record categories and types from farmers and workers, actors, and wealthy businessmen, like Sander, as well as, the "freaks" which were the subject matter for Arbus. The approach is frontal and lacking in artifice. Some of the images and conditions in which they were made are simple and primitive. He is more interested in the subject than in the techniques and fetishes of photography. Many of the images evoke grabs and fleeting encounters before the subjects might flee or change their mind. Some of this approach no doubt came from the exigencies of photojournalism where the photographer has little or no control over the circumstances of making images. It is field work where one copes as best as one can. There was no crew to set up lights or to orchestrate a perfect print. He shoots with a Hasselblad using available light and occasional flash. The resultant prints all have a square format.

We are riveted by the subject matter with its often horrific, humanistic content and rarely if ever by the "quality" of the print. This was often said of Arbus and others working in journalistic documentary traditions. It is a welcome alternative to the contemporary photo world where the great art stars create enormous, perfect prints.which are stunning, and spectacular, but, too often, cold and appealing to the crass. Contemporary large format photographs are often like big budget movies with incredible special effects but not much in the way of plot or content.

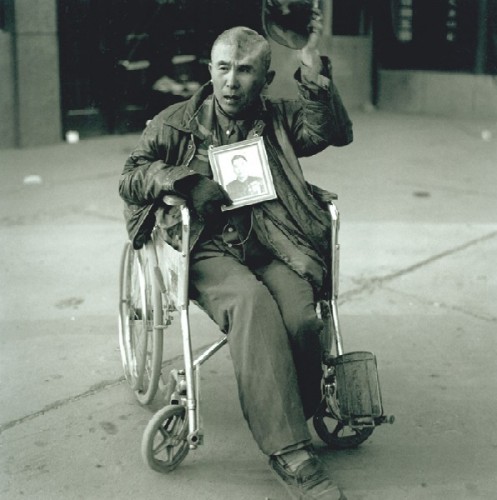

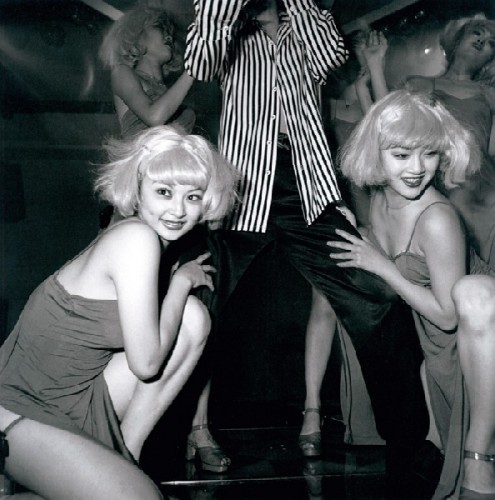

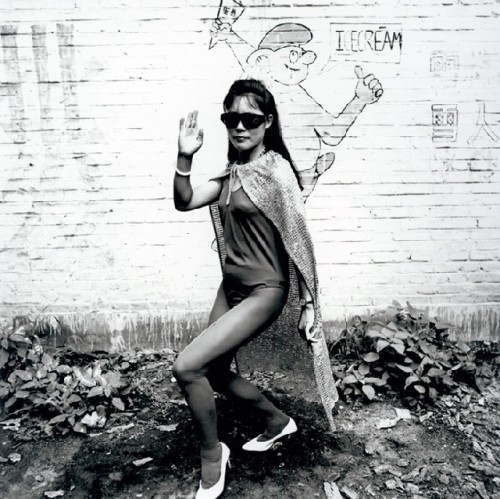

The artist is unflinching in his encounter with Chinese history and culture. This is represented in images of wax museums depicting the Emperor with his concubine. Or mannequins and actors portraying the abuses suffered during an invasion by the Japanese. The resultant piles with mummified corpses of mass graves in pits and caves are now tourist attractions. He is intrigued by traditional performances of theatre and opera. There is the dichotomy of an "ugly" woman "A Poetess, Beijing" and the "beauty" of "Transsexual Nude, Beijing." An ongoing theme is the notion of Love for Sale with pretty young girls, entertainers, dancers, prostitutes, and the grotesque queens of the traditional theatre. In the middle of the book, page 78, we encounter a group of "Nuns, Beijing." Here and there are Buddhist monks and Islamic girls. We are shocked by the many amputees. For me, the most fascinating and riveting image in the series "A Patient, Beijing" (page 192) depicts a frontal view of a man with a huge tumor, sitting like a squash on the top of his head, with other enormous tumors bulging from his right arm. We are stunned by the agony of encountering "An Old Beggar in a Wheelchair, Lintong County, Shaanxi Province, 1999" There is an enormous wedge on the top of his head where a slice of his skull is missing. Skin covers the sunken gap of this terrible wound. In his hand he holds a framed image as a young man dressed as a soldier with his chest covered with ribbons.

The fascinating question is why this work has been acquired for Williams and its students. Of the 13,000 or so objects in its collection WCMA owns some 800 photographs including this acquisition of 120 by Zheng. While its mission and mandate has evolved through the years it is primarily a teaching museum. When Tom Krens was director it broadened its reach with special exhibitions. During my meeting with Stomberg he touched on how the collection is used for courses all through the college. There are areas where faculty and students have hands on access to works. So the Zheng works will be used by future generations of students. Just as Lisa Corrin, the current director of WCMA, during the recent dedication ceremonies, described the new Sol LeWitt building and installations at Mass MoCA as the "newest and largest classroom of Williams College."

Yes, but why the Zheng acquisition I asked Stomberg? How did it come about and what was the motive? The first exposure to Zheng's work occurred a couple of years ago when Stomberg was in Seattle recruiting Corrin to come to Williams. There was a show "New Art from China" traveling through the International Center for Photography. The resources existed to acquire work through the Wachenheim Family Fund with a mandate to collect photography, African, and Asian art. The Zheng works fit two of the three criteria.

When Corrin joined WCMA she and Stomberg became increasingly excited by the opportunity to commission Zheng to create a set of silver gelatin prints. They compared the opportunity to the possibility of acquiring the complete set of Robert Frank's "The Americans" in 1957. What was affordable then is priceless now. In going forward with this commission Corrin and Stomberg project that this important work will be the nucleus for building a great collection of contemporary photography. It is the kind of bold and significant move that attracts other acquisitions and donations. Collectors want to give to museums where their works will be seen, studied, and appreciated.

It was particularly instructive to see how Stomberg and Corrin are using their new acquisitions. In addition to administrative tasks as Deputy Director of WCMA, over the past two years, Stomberg moved forward with the Zheng project. This entailed organizing and installing related projects covering several galleries of historic and contemporary material "Beyond the Familiar: Photography and the Construction of Community" "Fiona Tan: Countenance" and "Independent Film and Ethnography." We will have another report on these sidebar exhibitions and how they complement the Zheng exhibition.

What particularly intrigued and impressed me was the manner in which the large space has been installed with 120 individual works It was a daunting task which looks so clean, rhythmic and precise. The work has been orchestrated into clusters and groupings of varying density with intervals of single works hung on a line. The curator moves us through the space with deft and insightful precision. First we view several individual works before encountering the wall text. He compared this to the design and layout of the famous book "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men" where the "portfolio" of images by Walker Evans precedes the text of James Agee. We actually find a copy of that book in an adjoining gallery.

Stomberg seemed pleased that I engaged him about the challenges of the installation. I was surprised when he compared it to an album by Pink Floyd. He commented how today kids download a song with little sense of how that track fits into the vision and concept of an album. How a composer or artist moves us through the experience. He related how, for the most part, he kept to the ordering of the images in the book. In the book and exhibition the first image we encounter is "Buddha in Cage, Wutai Mountain, Shanxi Province, 1998." It is a metaphor for how the traditions of China are seemingly held captive by contemporary society. But the intervals and clustering were Stomberg's agonizing contribution. First the works were laid out on the floor of the gallery. All the while he was listening to CDs on a boom box. Now and then he would send the installers away while he lived with the work. The entire process took a week. A trained eye will appreciate the resultant love, care, and attention to details.

It is how a curator creates music with works of art. In this case poetic music conducted through a masterful orchestration of the most dark, horrific, and harrowing works imaginable. Also Sprach Zarathustra or The Dark Side of the Moon.