Spectacular Bauhaus Exhibit At MoMA

Brilliant Overview Through January 25

By: Mark Favermann - Nov 29, 2009

Armchair, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, 1927-30, Chrome plated tubular steel and leather

Eberhard Schrammen

Maskottchen (Mascot). c. 1924

Oak and miscellaneous exotic woods, turned, coated in places with colored and gold lacquer

Height: 14 9/16” (37 cm)

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin

Photo: Gunter Lepkowski

© Estate Eberhard Schrammen

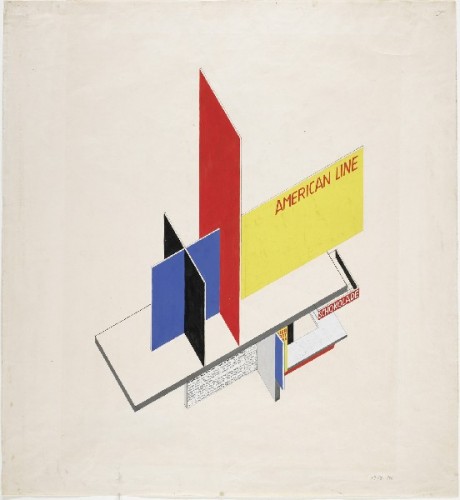

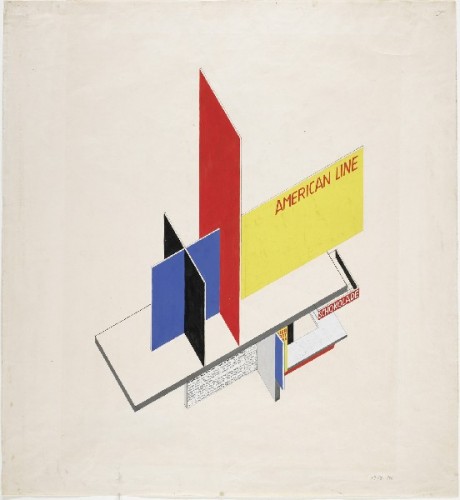

Herbert Bayer

Design for kiosk and display boards. 1924

Gouache, ink, pencil, and cut-and-pasted print elements on paper. 20 3/4 x 19 1/16" (57.7 x 48.4 cm)

Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of the artist

Photo: Katya Kallsen © President and Fellows of Harvard College

© 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

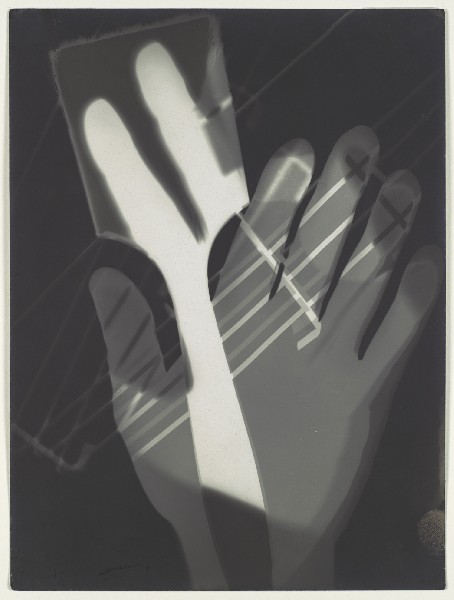

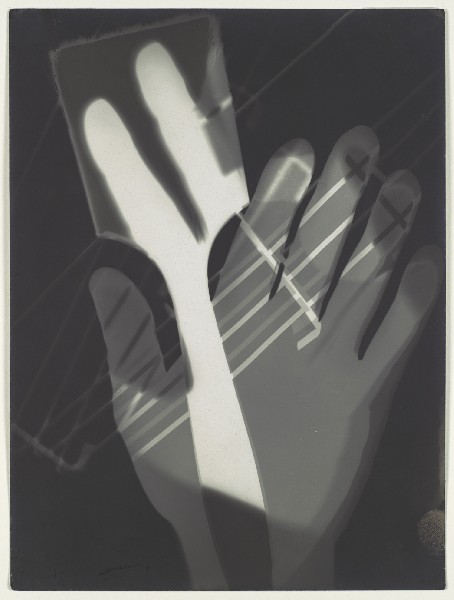

László Moholy-Nagy

Untitled. 1926

Gelatin silver print (photogram)

9 7/16 x 7 1/16" (23.9 x 17.9 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Ford Motor Company Collection, Gift of Ford Motor Company and John C. Waddell

Copy photograph © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

© 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

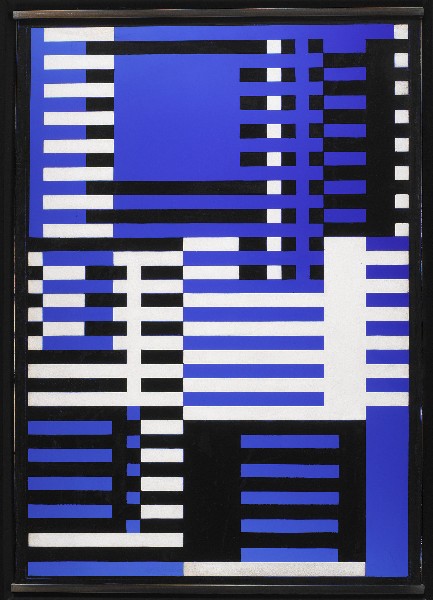

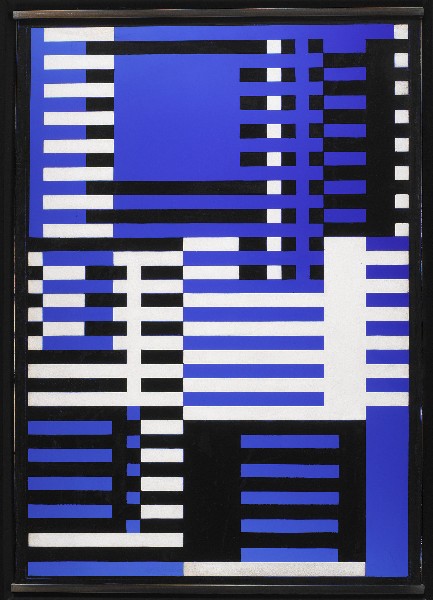

Josef Albers

Upward. c. 1926

Blue glass flashed on milk glass, sandblasted, with black paint

17 9/16 x 12 3/8" (44.6 x 31.4 cm)

Albers Foundation/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Tim Nighswander

© 2009 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Marianne Brandt

Coffee and tea set. 1924

Silver and ebony, lid of sugar bowl made of glass. Tray: 13 x 20 1/4" (33 x 51.5 cm)

Bauhaus-Archiv Berlin. Purchased with funds from the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin. Photo: Fred Kraus

© 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

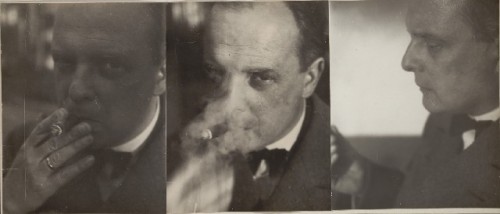

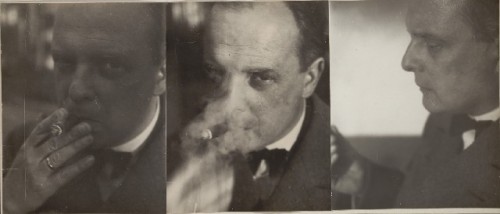

Josef Albers

Paul Klee, Dessau, 1929

6 3/4 x 16 7/16" (17.1 x 41.8 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gift of The Josef Albers Foundation, Inc.

© 2009 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists R

Anni Albers

Wall hanging. 1926

Silk (three-ply weave). 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm)

Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund

Photo: Katya Kallsen © President and Fellows of Harvard College

© 2009 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Josef Albers

Set of stacking tables. c. 1927

Ash veneer, black lacquer, and painted glass

Ranging from 15 5/8 x 16 1/2 x 15 3/4" (39.2 x 41.9 x 40 cm) to 24 5/8 x 23 5/8 x 15 7/8" (62.6 x 60.1 x 40.3 cm)

Albers Foundation/Art Resource, NY. Photo: Tim Nighswander

© 2009 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

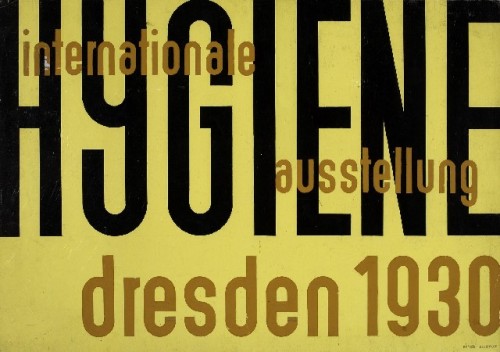

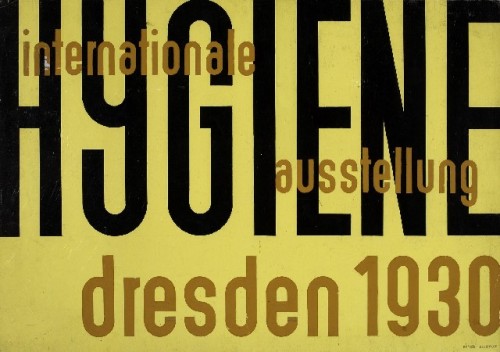

Erich Mrozek

Design for a poster for Internationale Hygiene Austellung (International hygiene exhibition), Dresden. 1930

Gouache on paper. 16 1/2 x 23 3/8" (41.9 x 59.4 cm)

Collection Merrill C. Berman. Photo: Jim Frank

Marcel Breuer

Wassily Chair, 1927 28

28 1/4 x 30 3/4 x 28" (71.8 x 78.1 x 71.1 cm)

The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Herbert Bayer

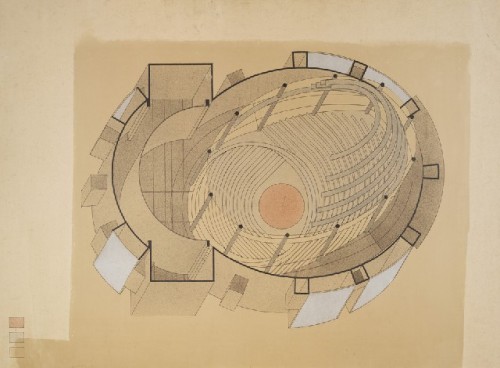

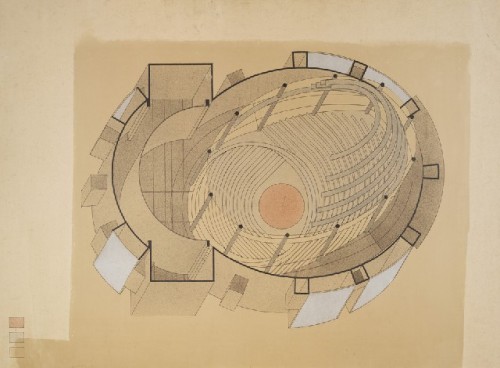

Walter Gropius. Drawing by Stefan Sebök

Total-Theater (Total theater), Berlin. Designed for Erwin Piscator. Isometric sectional view. 1927

Ink, gouache, and spatter paint on composition board. 32 5/8 x 42 11/16" (82.8 x 108.4 cm)

Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of Walter Gropius

Photo credit and copyright:

Photo: Katya Kallsen © President and Fellows of Harvard College

© 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

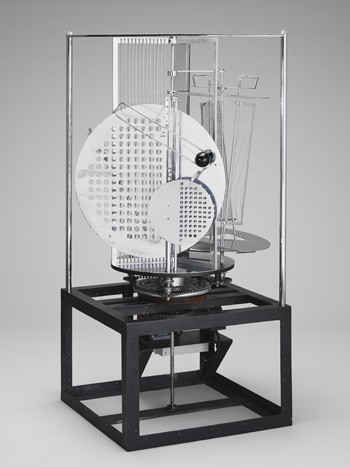

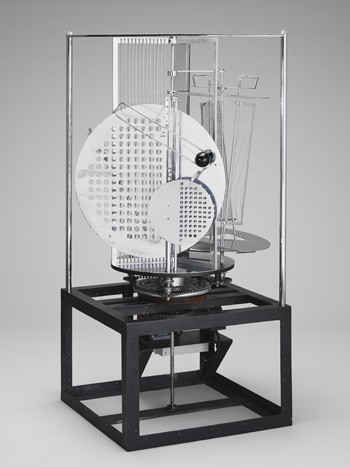

László Moholy-Nagy

Lichtrequisit einer Elektrischen Bühne (Light prop for an electric stage). 1930

Aluminum, steel, nickel-plated brass, other metals, plastic, wood, and electric motor. 59 1/2 x 27 1/2 x 27 1/2" (151.1 x 69.9 x 69.9 cm)

Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Gift of Sibyl Moholy-Nagy

Photo: Junius Beebe © President and Fellows of Harvard College

© 2009 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

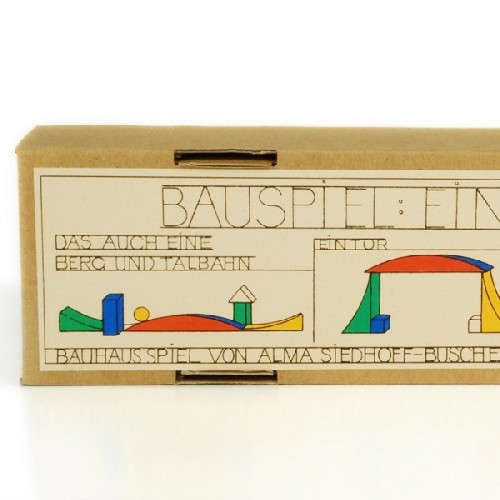

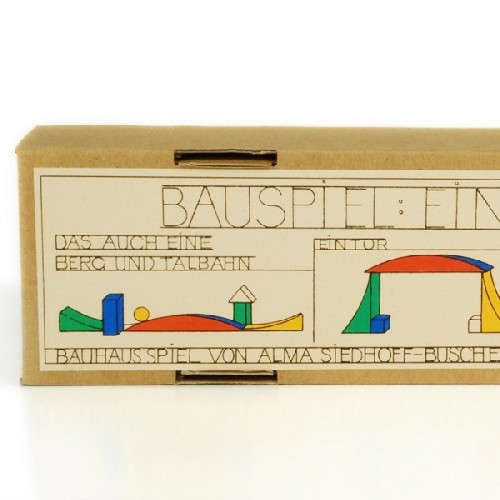

Box Detail for Blauspiel Schiff by Alma Buscher,1923

The Bauhaus is often shorthand for an elegant yet accessible style of international modernism. It is also the gold standard for collaborative and ground-breaking design. It is one of those legendary institutions and times that is like Camelot to artists, designers and architects. It is both mythical and a bit magical. Like Camelot, the Bauhaus was an utopian concept that expressed the best and most hopeful goals and greatest potential achievements. A lot of this magic is at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in a major and perhaps seminal exhibition, Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity (November 8, 2009 through January 25, 2010). It just does not get much better than this exhibit.

Founded shortly after World War I in Germany, the Bauhaus was the most famous and influential avant-garde art and design school in the 20th Century. Its artists, architects, designers and students were involved in an all encompassing, extraordinary and universal conversation about the nature of art in the modern era. Over the course of its relatively short 14 year history, it was located at Weimar, Dessau, and Berlin. The visionary mission of the Bauhaus was to rethink and restructure the very form of contemporary life. It included a philosophy to unify art, craft and technology.

The Bauhaus faculty and students used the facilities of the school as a venue for visual and material experimentation. These exercises had a transformative influence on design in the 1920s and 30s. The resonating effects of the Bauhaus still can be seen in our own design ethos and contemporary culture. Collaboration was the motto of the Bauhaus. The Bauhaus Holy Grail, the ultimate collaborative goal, was to create elegantly integrated interdisciplinary works.

The utopian ideal of the Bauhaus was for artists, designers and architects to have a totally modern opportunity environment to allow their visual dialogue to be manifested into a coherent approach to creativity. The machine was considered a positive element that underscored the importance of industrial and product design. Artists and designers worked across different mediums and technologies. To members of the Bauhaus community, this was the natural progression of the visual arts and crafts. Function and form were intertwined. Systemically modern architecture was to make use of this approach as well.

This exhibit organizes over 400 works to illustrate the broad range of the school's brilliant reach. These include industrial design, furniture, architecture, graphics, textiles, photography. ceramics. theatre/costume design, painting and sculpture. Prominent faculty and students represented in the show include Josef Albers, Anni Albers, Herbert Bayer, Marianne Brandt, Marcel Breuer, Lyonel Feininger, Walter Gropius, Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Lucia Moholy-Nagy, Oskar Schlemmer and Gunta Stolzl along with many other talented lesser known artists and designers.

Organized in the true spirit of the legendary institution by Barry Bergdoll, the Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design, and Leah Dickerman, the Curator of MoMA's Painting and Sculpture Department, this thoughtful and comprehensive exhibition, Bauhaus 1919-1933: Workshops for Modernity, was an interdepartmental collaboration. The exhibit opened 80 years after MoMA's founding and 90 years after the establishment of the Bauhaus itself.

The basis for the exhibition were 80 pieces from the Museum of Modern Art's own superior collection. Added to these were many works from three major German Bauhaus collections, the Anni and Josef Albers Foundation, the Centre Pompidou, Harvard Art Museums' Busch- Reisinger Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art as well as numerous public and private collections from around Europe and the United States. The visual richness of the works presented in this exhibit cannot be overstated as the quality and depth are outstanding and astounding.

The Bauhaus' history is certainly connected to the history of the Museum of Modern Art. In 1938, MoMA had its first comprehensive Bauhaus exhibit. That earlier exhibition, entitled Bauhaus, 1919-1928, was organized by the former school's founding director, Walter Gropius and designed by a former student and instructor, Herbert Bayer. It was an exhibit that strategically left out the Bauhaus's final five years that were led by Gropius' successors Hannes Meyer and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Rightly or wrongly, this 1938 exhibit, its catalogue and its interpretive focus literally informed Americans for the next generation about the Bauhaus.

MoMA's architecture and design department was formulated in part by looking at the Bauhaus. MoMA founder Alfred Barr, Jr. was particularly impressed by the school when he visited it in 1928 for a few days. He commented to Gropius about the impact that the experience made upon him considering it a major aspect of his education. MoMA's collection was the first to have such a wide range of art and design works. MoMA has continued this collecting and exhibition direction throughout its history.

This second Bauhaus exhibit allows for an expanded experience with a broadened new perspective. Organized in a loose chronological way with specific sections focused on Weimar, Dessau and Berlin years, the curators have followed the various directors tenures with Walter Gropius (1919-1928), Hannes Meyer (1928-1930) and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1930-1933). Each one of the school's directors was a major 20th Century architect/educator, and each had a distinctive design philosophy.

Housed in three very different cities with three very distinct cultural and political environments, the Bauhaus started out in 1919 in Weimar, the hometown of Goethe and Schiller, then was forced by political opposition to move to the industrial city of Dessau in 1925 to the buildings designed by Walter Gropius. The Nazis closed the school in 1932, but a core group of students and faculty kept it going in Berlin for another year. Luckily the Bauhaus legacy has lived on and is now being celebrated by this magnificent exhibition.

The school literally functioned as a cultural think tank for trying times. Its diverse faculty of prominent artists, designers, and architects engaged in a 14-year dialogue and sometimes debate about the nature of art in the age of expanding technology, industrial production, and global communication. The exhibition reflects the added value interrelationships among diverse media, mixing works from the school's different workshops. It traces formal and conceptual ideas translated into objects made of different materials and for different purposes. The clear focus on cross-pollination resonates with our own time. Interestingly, the color palette used in the exhibition comes from those that Gropius used in houses he designed for himself and the Bauhaus masters in Dessau in 1925. Along with the standard Bauhaus colors of white, black, the three primaries and gray, unexpected colors such as gold, pink, and tangerine are used.

There are so many noteworthy pieces in this show that it is hard to single out just a few. However, there are several standouts. Many of the pieces are as fresh and strong today as they were almost 90 years ago. There are many Bauhaus icons such as Marcel Breuer's tubular steel furniture, László Moholy-Nagy's oblique angle photographs and Wilhelm Wagenfeld's domed table lamp, as well as works that just surprise, like Lothar Schreyer's design for a coffin (1920) or Kurt Kranz's project for an abstract cinema (c. 1930).

Included are rare textiles by Anni Albers woven in the Bauhaus period (most seen today are rewoven later) and others by Gunta Stölzl; important paintings by Vasily Kandinsky, Paul Klee, and Oskar Schlemmer (Bauhaus Stairway from 1932); graphic designs by Herbert Bayer and Joost Schmidt; a range of photographs, including a selection of Lucia Moholy's close-up photographic portraits; stained glass windows by Josef Albers; a tea set by Marianne Brandt; and marionettes by Kurt Schmidt from the 1923 Bauhaus production of The Adventures of the Little Hunchback directed by Oskar Schlemmer.

Marcel Breuer's African Chair (1921) created in collaboration with the weaver Gunta Stölzl is a gem. Made of painted wood with a colorful woven textile, this chair embodies the spirit of the early Bauhaus in its romantic experimentalism. The chair was presumed lost for the past 80 years—. The only documentation available was a black-and-white photograph— until 2004, when its owners offered the chair to the Bauhaus-Archiv in Berlin. This is the chair's first appearance outside of Germany.

One of the most elegant and tantalizing designs in the exhibition is a toy. And this toy represents the philosophy and mission of the Bauhaus at many levels. According to University of Chicago Art Historian Christine Mehring, the sometimes profound German philosopher/critic and sociologist/essayist Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) once said that the "most extreme concreteness of an epoch {can be seen} as it appears in children's games or in a building." This appears to be very true with the Alma Buscher's Bauspiel "Schiff" ship building toy (1923). Working in the Bauhaus wood shop, the colorful wooden toy was created as part of a school project for a children's area at a model house that the school was to exhibit the following year.

This is a construction toy of different size and shaped pieces that can be arranged in many different forms. The various blocks are colored in primary red, blue and yellow with green and white blocks as well. These are geometric pieces that can become a ship, a sloping road or hill, a gateway, a person, etc. Here, "a concreteness of epoch" certainly states a realm of possibilities elegantly much like the Bauhaus itself did.

From the early 1930s, the Bauhaus's many prominent artists, architects, designers and former students were dispersed primarily throughout Europe and North America. Besides continuing their own design, architecture or art, several extended careers as educators mentoring the next generation of creative individuals. Walter Gropius first went to London and eventually chaired the architecture department at Harvard University's Graduate School of Design. Mies van der Rohe settled in Chicago and headed up the architecture program at what became the Illinois Institute of Technology. Swiss-born Hannes Meyer worked first in Moscow until being thrown out by the Soviet regime and then worked at the Intituto del Urbanismo y Plantification in Mexico City. Later he returned to Geneva where he died in 1954.

After resigning from the Bauhaus in 1928, Hungarian Laszlo Moholy-Nagy worked on film and stage design in Berlin. He followed this with work in Paris and Holland. In 1935, he tried with Gropius to start a Bauhaus in London but could get no appropriate support for it. He came to Chicago at the urging of Walter Paepcke, the Chairman of the Container Corporation of America to become the director of the New Bauhaus. The school's philosophy was based on the original's. The New Bauhaus lost its financial backing after only a year and closed in 1938. In the 1940's, Moholy-Nagy opened the School of Design that later became the Institute of Design which is now part of the Illinois Institute of Technology (ITT).

Josef Albers immigrated to the United States in 1933 and became the head of another "new Bauhaus," Black Mountain College, another legendary school, in North Carolina until 1949. His students there included Robert Raushenburg and Cy Twombley. In 1950, Albers became the head of Yale University's Department of Art and Design. Albers taught there until 1958. Prominent students from this period included Eva Hesse and Richard Anuskiewicz.

Other artists, designers and architects found teaching jobs in many places, but there never was another place quite like the Bauhaus. Though several efforts were attempted by former faculty and students, there was never a second act for Bauhaus.

Like Camelot or any other human involved utopian entity, the Bauhaus was not a perfect place. Collaboration was actually quite limited. Though there were some projects mostly furniture or set design that were clearly collaborative, the vast majority of projects were individual and often very personal. However, there was an amazing group of critical and creative thinkers who could review and suggest refinements to those willing to listen and even learn.

Although women were the majority of students at the Bauhaus in the early years of the school, women were not treated very well there. Gropius felt that women could only think in two dimensions while men could think in three. He had a rather medieval vision of women's place. Women were generally relegated to textiles, ceramics and more traditional handcrafts. Architecture was introduced in 1927 and was only for men. By 1930, the Bauhaus had become mostly an architecture school. Marianne Brandt had to fight to get to do metalcraft as did Alma Buscher for the woodshop. Brandt became one of the preeminent designers in the field and one of the few female Bauhaus masters.

Though it was clearly a function of the times and culture, the socially liberal and intellectually open environment did not foster a sense of sexual equality. Few women were allowed to shine there. This was a male-oriented society. However, it was probably women who fostered actual collaboration and were the glue that led to the Bauhaus legacy. An example of this is the rarely seen extraordinary collaboration of Marcel Breuer and weaver Gunta Stolzl who created "African Chair" (1921) that is a featured element in the MoMA exhibit. But, Breuer is widely known and Stolzl is but an obscure footnote.

Also, the Bauhaus effort to involve the school in contemporary commercial ventures was less than satisfactory. Production of ceramics, metalcraft and other items tended to be too expensive to distribute to the masses to develop profits worthy of the concentrated efforts. The Bauhaus mass mission was to educate. Commerce was not a simple outcome of the school's great talent or energy. The Depression not withstanding, the school's products may have just been a bit too elitist for mass consumer appeal.

Fittingly, there is a magnificent catalogue for the exhibit as well. Bauhaus 1919–-1933: Workshops for Modernity features over 400 full-color plates, complemented by rich documentary images. The catalogue includes two essays by curators Barry Bergdoll and Leah Dickerman that share thoughtful new critical perspectives on the Bauhaus. Thirty shorter essays by over 20 leading scholars discuss specific works shown in the exhibition. An exquisitely illustrated narrative chronology opens a window on the Bauhaus's history. This wonderful book acts as a guide though important events, exhibitions and publications. The book is published by The Museum of Modern Art, Hardcover, 12h x 9.5 in; 328 pages, 400 illustrations, $75.

Seminal prototypical visual statements were never again produced in such quantities by any other art and design school. This golden place in a golden moment of creativity was never again replicated to the same mythic proportions. There was a sense of joy associated with the Bauhaus. Its artistic memory or creative legend still bring a sense of almost spiritual elation about the best in modern art and design. Visiting this exhibit is a joyous visual, cultural and historical celebration. It should not be missed.