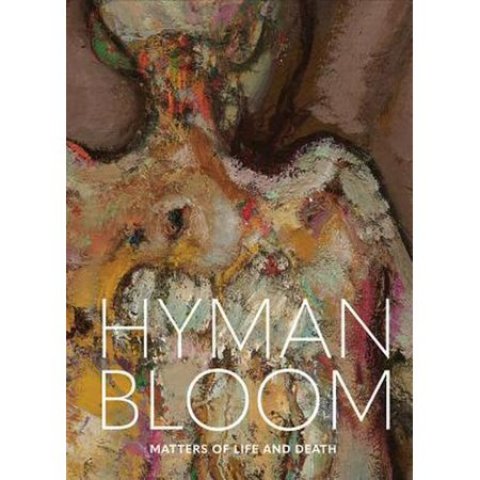

Hyman Bloom Matters of Life and Death

Putrid Cadavers a Late Bloomer for the MFA

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 28, 2019

Hyman Bloom Matters of Life and Death

Erica E. Hirshler with an essay by Naomi Slipp

Director’s foreword by Matthew Teitelbaum

MFA Publications

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

112 pages illustrated, with notes, list of illustrations, index and acknowledgement. Published 2019

ISBN 978-0-87846-861-4

Modern Mystic: The Art of Hyman Bloom

By Henry Adams and Marcia Brennan

Foreword by Debra Bricker Balkan with contributions by Robert Alimi

ARTBOOK/D.A.P. New York

192 pages illustrated, with list of plates, selected exhibition history, chronology, selected bibliography, and index. Published 2019

ISBN 978-1-942884-39-2

In 1959 an exhibition organized by Wellesley College Art Museum “Four Boston Masters: Copley, Allston, Prendergast, Bloom” transferred to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Hyman Bloom was then teaching at Wellesley.

In an act of atonement for egregious neglect, with media hoopla following a lapse of more than a half century, the MFA is featuring some 70 paintings and drawings. Now on view is “Hyman Bloom Matters of Life and Death.”

The stunning, morbidly galvanic exhibition through February 23, was curated by Erica E. Hirshler. During a tour of the galleries she explained a decision to focus on the most difficult and challenging but signature works. This is deliberatly not a retrospective which she explains has been done elsewhere.

The cadaver paintings started in the 1940s when he and David Arsonson visited the morgue of the former Kenmore Hospital. Bloom also attended autopsies and surgeries. There is a long tradition going back to the transgressive, illegal anatomy studies of Leonardo da Vinci.

There have been objective renderings of procedures and cadavers from Rembrandt to Gericault and Eakins. Those of Bloom, however, are not. In his painting the flesh is occasionally putrid. Some images of dissected young women have a Jack the Ripper eroticism.

There is a drawing evoking the legend of Marsyas. The satyr performed a pan's pipe in a contest with Apollo who played harp. For challenging a god he was flayed alive. A vivid painting of a flayed back is titled "Self Portrait" (1948). With references to Rembrandt we encounter "Slaughtered Animal" 1953. "The Hull" (1952) is a horrific view of a woman's ribs suggesting the structure of a ship. The frontal nudes with rotting flesh "Corpse of Man" (1944 ) and "Female Corpse, Front View" (1945) are not for the squeamish.

The painting in gray, pinkish flesh tones of a model with flabby flesh "Seated Old Woman" (circa 1972-73) will evoke the British artists Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud. In 1960 Bloom and Bacon were paired at the Art Galleries of the University of California. Then they were considered as equivalent while today they are not.

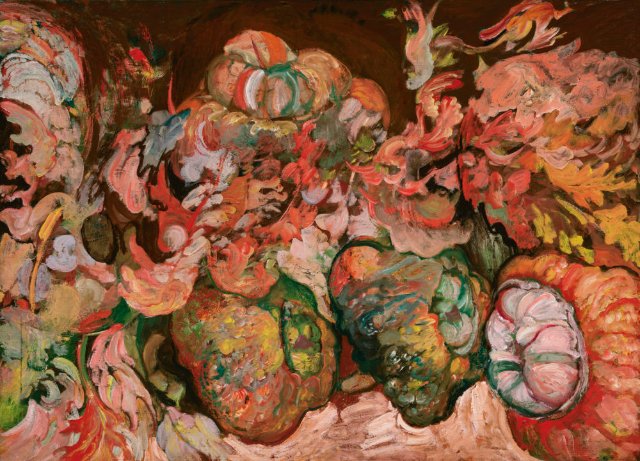

Bloom regarded these provocative works as beautiful, however macabre. He was surprised at the reactions they evoked. Dealers and museums censored them and reviews could be scathing. They were a tough sell compared to his entangled landscapes, still life paintings, and Judaica.

Hirschler has made a bold move and aggressive statement to highlight the most controversial aspect of a “rediscovered” artist.

The reality is that the work of Bloom has been hiding in plain sight. Growing up in Boston, starting in the 1950s, I have always been aware of Bloom. By the late 1960s I was on the outer edge of the cult that continues to celebrate him. That astral plane was energized by his interest in the occult, Indian music and preference for seclusion.

He made a fetish of not participating in the art world. He did not attend openings, was indifferent to reviews and publicity, rarely allowed himself to be photographed or interviewed. Those who did gain access to the studio, as Hirschler reports on a single visit, “unfinished” works were turned to the wall. One was not allowed to tape record or take notes.

Accepting those terms Dorothy Thompson made many such visits. As she told me rushing home she would recall the conversation with notes. She became a major resource for understanding the work.

That resulted in the 1996 exhibition “The Spirits of Hyman Bloom: Sixty Years Of Painting and Drawing.” It was shown at what was founded as the Brockton Art Museum. It was then known as the Fuller Museum of Art which today is the Fuller Craft Museum.

Uniquely, accompanied by his wife Stella, Bloom attended the opening. As did his childhood fellow student, Jack Levine.

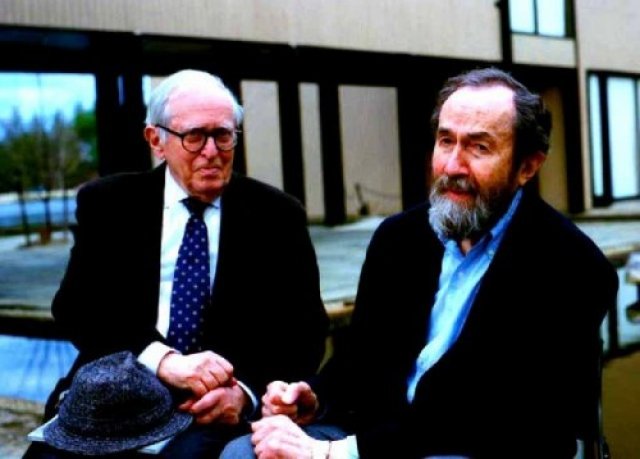

At the time David and Nancy Sutherland were making a documentary film about Levine. I covered that project for Art New England and spent time with the Sutherlands and Jack in Newton and his studio in New York. Jack moved there when he married the artist Ruth Gikow in 1946. He remained a fan of the Red Sox.

If Hyman was indifferent to art critics Jack held them in contempt. Despite which we got along just fine. He told me that he would like to do a book with journalist Jimmy Breslin. The monograph was done with American art historian Milton W. Brown. In the film there is a shot of them taking in a ball game.

In addition to that 1996 exhibition in Brockton there was a 2006 exhibition “Hyman Bloom: A Spiritual Embrace” at the Danforth Museum of Art in Framingham. It focused on his paintings of rabbis holding torahs. Under former director, Katherine French, the museum developed a mandate to show and collect Boston Expressionism and the generations of figuration that evolved from it.

After three years of living in New York I returned to Boston in 1968. One of the first shows I covered for Boston After Dark was a traveling show “The Drawings of Hyman Bloom” at the Boston University Art Gallery.

Bloom was focused on drawings at the time. The large imaginative landscapes, tangles of woods, evoked Altdorfer with a psychedelic twist. He took LSD with Dr. Max Rinkel, who briefly, was my shrink as well. I asked him about Bloom but received no answer. During the Brockton opening I asked Bloom about Rinkel but there was no response to the question.

It struck me as strange and insulting that a major show of drawings traveled from the San Francisco Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of Art to BU rather than the MFA. The exhibition received no media attention in Boston other than my own.

Intermittently the ICA has shown Bloom but now appears to have little or no interest in Boston’s art history. The last show was “Boston Expressionism: Hyman Bloom, Jack Levine and Karl Zerbe” in 1979. That was under director Stephen Prokopoff who also had a popular show of American Impressionism. It included attractive but enervating paintings by Boston artists. During a talk at the Copley Society the architect Frank Lloyd Wright told the audience that Boston needed "A hundred first class funerals."

Given the lapses of the MFA and ICA that role deferred to the De Cordova Museum. There was a messy and badly botched 1986 exhibition “Expressionism in Boston: 1945-1985.” It is a show that the MFA should have done. The norm is that once done, however inaccurately, the theme is not revisited for at least a generation. By now that statute of limitations appears to have lapsed.

There was a better and more scholarly attempt with “Painting in Boston:1950-2000.” In the 2002 catalogue essay curator Nicholas Capasso, now director of Fitchburg Art Museum, stated.

“At mid-century, Boston was home to a vital, home-grown group of painters, the Boston Expressionists, at the apogee of their powers and reputations—and anyone paying attention to contemporary American art at the time knew it. As early as the thirties, the young Boston Expressionist painter Jack Levine began receiving national attention and acclaim. His work was included in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Annual Exhibition of Contemporary American Painting in 1937, and the following year found his paintings in Three Centuries of American Art, an exhibition organized by New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) for the Jeu de Paume in Paris. In 1942, Levine was selected by curator Dorothy Miller, along with fellow Boston Expressionists Hyman Bloom and David Aronson, for her prestigious MoMA exhibition Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States. Aronson reappeared in Miller’s Fourteen Americans in 1946, again at MoMA. During the forties, Bloom, Levine, Aronson, and Karl Zerbe showed regularly in New York commercial galleries, and ARTnews began to identify and discuss the growing school of expressionist painting in Boston.2 Also in 1946, Bloom, Levine, and Zerbe found themselves among the important artists listed on Ad Reinhardt’s syndicated drawing How to Look at Modern Art in America, a semi-satirical art historical evolutionary tree with its roots in Post-Impressionism, a Cubist trunk, and branches and leaves representing then-current stylistic directions.

“And then there is Hyman Bloom, arguably the greatest of the Boston Expressionists in terms of both aesthetics and reputation. In 1950, his work was placed in the American exhibition at the Venice Biennale, alongside paintings by Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, John Marin, and Jackson Pollock, and Elaine de Kooning wrote an extended article about his creative process for ARTnews. In 1954, a Bloom retrospective, organized by The Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, traveled to venues across the country and culminated at the Whitney Museum. In the same year, his painting Apparition of Danger appeared on the cover of ARTnews, and within the magazine’s pages critic Thomas Hess heralded the Boston Expressionist as “one of the outstanding painters of his generation.”

The current MFA exhibition atones for neglecting Bloom. While welcome it is lip service to generations of Boston artists and more broadly for missing the boat on global modernism and contemporary art. With mixed results that started to change with the appointment of Kenworth Moffett as, initially, part time curator of contemporary art in 1971. His tenure at the MFA ended in 1984.

The appointment of Moffett was one of the last acts of director Perry T. Rathbone who was ousted because of the Centennial Raphael scandal. The museum's trustees initiated an Ad Hoc Policy Report. One of its bullet points entailed a change toward modern and contemporary art. MFA curator of American Art, Theodore E. Stebbins. Jr. stated at the time that "The museum of fine arts is getting into 20th century art now that it is almost over." How much progress the MFA has made from then to now is a matter of debate.

There have been a number of MFA exhibitions surveying the art and architecture of Boston from Colonial time until the 1940s. That’s precisely when the leading artists, The Boston Expressionists, and the next generation were Jewish.

The last attempt at a survey was “The Bostonians: Painters of an Elegant Age, 1870-1930” curated by Trevor Fairbrother. It was a pretty and well mannered show.

With the Bloom show, and other curatorial and programming efforts, the museum and its director, Matthew Teitelbaum, are addressing longstanding issues of anti Semitism and racism that have recently come to a head. Benign neglect no longer works. There are gaping holes to plug for the sinking ship of public opinion.

The focus on Bloom is bolstered by the assessment that he was the best Boston artist of his generation. Levine, who followed a different path with an identical education, is no less important. The third part of the triumvirate, Karl Zerbe, is also due for critical reevaluation.

During my conversation with Hirschler I asked when the MFA plans to do a Levine show? There was a fudged response. Through the Lane Collection the MFA now owns major works by Bloom and Zerbe but only an early minor work by Levine. There seems to be no interest in a significant acquisition. The MFA's Bloom catalogue barely mentions Levine. Nor do any of the many Bloom reviews other than tangentially. There is no cult following for Jack.

By cherry-picking the, best of Bloom for the exhibition and catalogue essay, Hirschler has avoided getting into the weeds that ensnare a broader understanding of the artist. For that we have the excellent and meticulously researched book “Modern Mystic: The Art of Hyman Bloom” by Henry Adams and Marcia Brennan. It is the perfect companion volume as I found when researching for this review.

Adams richly quotes from critics and art historians- Sydney Freedberg, Millard Meiss, Brian O’Doherty, Thomas Hess, Hilton Kramer, Sebastian Smee- who wrote about the work starting in the 1940s. Unfortunately, I have a problem with the design of the book. These extensive quotes are grayed out. The intent is to set them off from the text but they are difficult to read.

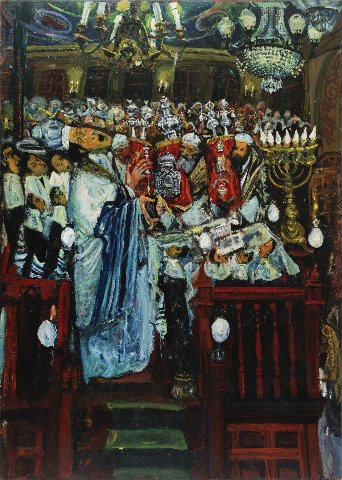

The son of orthodox Jews initially Bloom aspired to be a rabbi. Later he “gave away his hat” and pursued a spectrum of primarily Eastern religions and philosophies. He and Levine created Judaica for which they were pigeonholed as Jewish artists. Asked about it Jack said “I came by that theme honestly.”

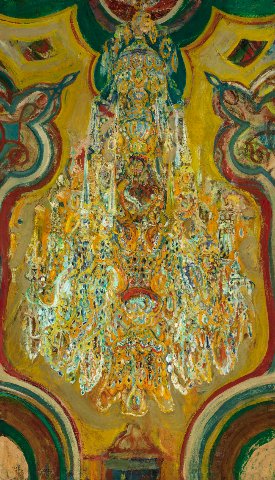

Sutherland recalled a Hilton Kramer review in which he stated that when walking into the gallery he could smell the pastrami. Writing about Bloom’s painting “The Synagogue” (ca. 1940) for Commentary in 1955 Kramer was crass if not anti Semitic.

“To the 'foreign' eye, which brings no associations to it, it must be as absorbing as a kosher dinner—a matter of taste. But for the observer who has associations with this imagery from childhood onwards, Bloom’s Jewish paintings stimulate the same surprise and dismay one feels on finding gefilte fish at a fashionable cocktail party” he wrote.

When we met at Skowhegan School of Art I confronted Kramer about his remarks. He replied “It was just a matter of one Jew criticizing another Jew.”

In a 1954 interview with Yale art professor Bernard Chaet, Willem de Kooning indicated that he and Jackson Pollock both considered Bloom to be “America’s first abstract expressionist.” Initially, Bloom was accepted into the canon of abstract expressionism by Clement Greenberg, or The New York School by Harold Rosenberg. Critical status lapsed for Bloom because he never abandoned figuration or moved to Manhattan.

In the reviews for the MFA exhibition Bloom is referred to as a Boston Expressionist and Abstract Expressionist. I have come to believe, as Adams suggests, that neither category applies.

The norm is for critics and art historians to herd artists, like cats, into groups, categories or schools. Let’s pause to deconstruct Bloom.

When teenagers, under the tutelage of Harold K. Zimmerman, who taught them to draw from memory and imagination, and Deman Ross, who had esoteric theories of color and painting, they were virtually brothers.

Levine started with Zimmerman from 1924-1931 then at Harvard with Ross from 1929-1933. Bloom started separately and a bit later with Zimmerman. He took Saturday classes at the Museum School while in high school. Ross, who was wealthy, paid Zimmerman as well as a stipend to the boys. They shared a studio but separated when the money stopped. By then they signed on for the Easel project of the WPA. Working slowly Bloom wasn’t able to keep pace with turning over paintings to stay in the program. A Levine painting from the WPA entered the MFA collection. Another, “Sting Quartet” was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While the term expressionism loosely applied to Bloom it does not to Levine. Bloom might better be viewed as a visionary, surrealist or figurative expressionist. He gained early recognition for MoMA and NY gallery exhibitions. Levine moved to NY but that failed to improve his status with critics. He was lumped with social realism which, with regionalism, was dumped when the nexus of the art world transferred from Paris to New York. That shift is discussed by Irving Sandler in "The Triumph of American Art" and Serge Guibault in "How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art." Because of its sustained commitment to figuration contemporary Boston art continues to be regarded as provincial.

Adams perceptively argues that dubbing Karl Zerbe a Boston Expressionist is inaccurate. He was born in Germany in 1903 and fully formed as an artist when he emigrated and became director of The Museum School from 1937 to 1955. His expressionism is rooted in European modernism but he was a significant influence on students of The Museum School.

There is a larger topic about the Germanic roots of the arts in Boston from the BSO to MFA and Harvard University Art Museums. Suffice it to say that Boston has a Nordic cultural orientation. It was Germanic, for example, compared to roots of MoMA which were dominantly French. Until the 1930s, when Jewish immigrant artists emerged, the orientation of the MFA was also French with taste for impressionism and post impressionism. Under MFA director, Perry T. Rathbone, and his sidekick Hans Scwarsenski, there was a paradigm shift to the Germanic.

From the 1940s through post war era the dominant Boston artists were European Jews. Jack Levine (January 3, 1915 – November 8, 2010) was born in Lithuania. Hyman Bloom (March 29, 1913 – August 26, 2009) was Latvian-born. Karl Zerbe (September 16, 1903 – November 24, 1972) was born in Berlin, Germany.

There are other leading Boston artists of the next generation. David Aronson (October 28, 1923 – July 2, 2015) was born in Lithuania. Also Arthur Polonsky (June 6, 1925 – April 4, 2019), Barbara Swan (1922-2003), Bernard Chaet (born 1924, Boston, MA - died 2012) and my colleague Lois Tarlow who was married to Polonsky. Henry Schwartz (1927-2009) was an amazing artist and teacher. The African American artist Allan Rohan Crite (March 20, 1910 - September 6, 2007) was a graduate of The Museum School. The Lebanese poet and artist Kahlil Gibran (1883-1931) lived and worked in Boston. As did his godson, the sculptor Kahlil G. Gibran (November 29, 1922 - April 13, 2008). With his wife, Jean, they wrote a biography of the poet/artist.

If Teitelbaum and the MFA intend to do the right thing they owe us group shows and retrospectives of that distinguished list of Boston artists. Don’t hold your breath. These artists are being shown at the Danforth Museum, Boston Public Library, and curated by Jean Gibran, at Boston’s St. Botolph Club.

The Hirschler show includes some of the juvenilia that Bloom created for Zimmerman and Ross. I vividly recall an afternoon at the Fogg Art Museum with the Sutherlands and Levine. With the help of curator Agnes Mongan we watched as Levine viewed and offered anecdotes about a collection donated by Ross.

I was intrigued by a Levine drawing of a BSO cellist. He had drawn it from memory. Another was broken down with lines drawn following the theories of dynamic symmetry of Jay Hambridge. Levine recalled it as an assignment from Ross who had unique concepts for composition.

My visit with Bloom and Hirshler was emotionally overwhelming. It is work that I have been looking at and thinking about since I was a teenager. I vividly recall Gibran's welded sculpture “John the Baptist” which won first prize at the Boston Arts Festival. Bloom and his school were shown by Boris Mirski on Newbury Street.

Bloom migrated to Hyman Swetsoff Gallery. He had been employed by Mirski as was another dealer Alan Fink of Alpha Gallery. Swetsoff was the most progressive Boston gallerist of his generation. In 1968 he was murdered by rough trade.

During 1960 I studied chemistry at Harvard Summer School. In the Yard I became friends with Judy Goldberg. She took me home to see drawings by Bloom which her father, Jerry, collected. He told me that he bought his first drawing from Swetsoff who soon borrowed it back to loan to an ICA show. It confirmed he was doing something of significance.

The most powerful memory of that visit was a drawing hidden behind a door. “Female Cadaver” (1954) evokes the ecstasy of Bernini’s “Blessed Ludovica Albertoni” (1671–74). She is ripped open from sternum to pubic bone.

I told Hirshler about this long ago encounter. Walking into an adjoining gallery she asked if it was how I remembered it. “Exactly,” I replied, “It’s the kind of experience you never forget.”