Jessica Park at The Good Purpose Gallery

Visions on the Spectrum II in Lee, Mass.

By: Alex Elvin - Nov 25, 2012

If you live in Berkshire County, you may have encountered Jessica Park’s vibrant architectural paintings– in a post office or a restaurant, in a fine arts gallery, or in one of the three books (written by local authors) about her life and work.

As part of its ongoing effort to support the arts for students with autism and other learning differences, the College Internship Program in Lee, Mass. is featuring Park’s paintings, and also the glass sculpture of Hoogs and Crawford, at its Good Purpose Gallery through January 2, 2013.

Park, who lives in Williamstown, Mass., and is a clerk in the Williams College mailroom, was diagnosed with autism in 1961 at the age of three. She began drawing as a teenager, and with the encouragement of her family and friends, has developed a painting style .

She often paints on commission, but also chooses her own subjects (almost always architectural) and makes cards to give to friends and family on special occasions.

The largest exhibit of Park’s work to date, “Visions on the Spectrum II” includes full-size paintings, and for the first time, a selection of cards, which, interestingly, are mostly non-architectural. Several high-quality giclee prints, are also included in the show.

The CIP was founded by Michael McManmon in 1984 to provide teenagers and young adults with learning differences the comprehensive life skills to help them succeed in college and adulthood. McManmon was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome in his early fifties. His drawings, paintings and sculptures were featured at The Good Purpose Gallery in October.

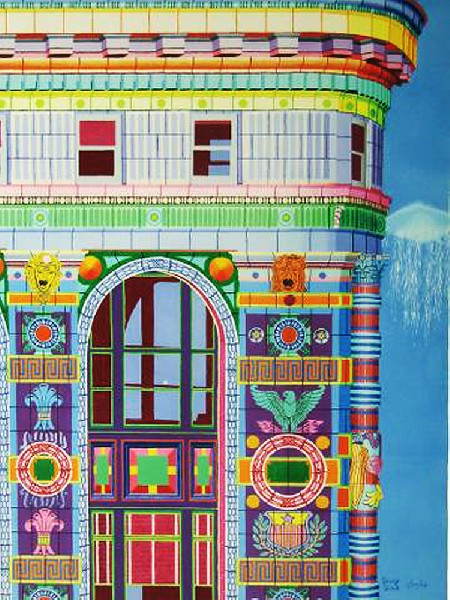

Dianne Steele, coordinator of The Good Purpose Gallery, described what she sees as the three elements that make up Park’s style. First, she said, is its obsessive attention to detail. Every architectural feature in her paintings, including subtle imperfections, is reproduced with near-photographic accuracy.

“And where she diverges is in her color,” Steele said. “She has ultra-realism in her detail of the architecture and then she has her fantasy colors and it makes this incredible juxtaposition that’s so striking and fun. It has a sense of humor, it’s life-giving, and I think that’s why it works. If the lines were unreal like the color, it wouldn’t do the same thing to you . . . so that is definitely her own signature.

She has a really interesting perspective choice.”

In one painting, for example, “it’s like she’s sitting on the ground looking up at the building, and she doesn’t include the whole building, she just takes a piece of it that’s interesting to her, cuts the windows right in half, which is definitely an indication . . . of being on the spectrum – having an unusual perspective, bringing out unusual detail.”

Still another feature of her work is the presence of atmospheric phenomena such as bright flares of color, jagged lightning shapes and other strange events. Park has a fascination for stars, which she usually paints in their actual positions and magnitudes.

The idea of an autistic spectrum, referring to a range of conditions including autism and Asperger’s syndrome, emerged in the 1970s and has broadened our understanding of autism and helped improve diagnosis. “Visions on the Spectrum II” is part of an ongoing series featuring artists living with autism and other learning differences.

Many people on the spectrum display higher-than-average abilities in art, music or math, or have a gift for remembering certain facts. In many cases, these skills facilitate greater involvement in society and allow those with difficulty communicating to connect with others where words can fail.

Two striking examples are the careers of Stephen Wiltshire, who reproduces cityscapes, sometimes after seeing them only once, and Richard Wawro, who drew detailed landscapes in crayon despite the fact that he was legally blind. Both artists have achieved worldwide recognition.

The styles of artists with autism are as different from each other as fingerprints. But what they often share is an exacting attention to detail and recurrent subject matter. This is certainly true for Park, whose subject matter consists almost entirely of architecture.

In Exiting Nirvana: A Daughter’s Life with Autism, Park’s mother, Clara Claiborne Park, describes her daughter’s painting style as reflective of her condition. “Here is autism in its core characteristics, literal, repetitive, obsessively exact – yet beautiful. In her paintings reality has been transfigured.”

But more, she says, than simply reflecting her inner world, her daughter’s art – and that of countless others on the spectrum – brings that world into communication with the world of others.

“Who wouldn’t want a painting of their house, recognizable to the last detail, but shimmering in colors no householder could conceive? Especially when they can get their favorite constellation thrown in?”All of us are fascinated at times by new ways of experiencing the familiar.

“Art is important in itself,” Park writes. “But for Jessy it has other kinds of importance. It brings her into contact with people. It enhances her communication skills. It gives her a productive way to fill the empty time after work is done. Compared with these advantages, it hardly seems significant that it allows her to make money.”

In recognizing the personal and social benefits of art, the CIP provides opportunities at each of its six locations– in Massachusetts, New York, Florida and California – for students to interact with local artists and to develop their own artistic skills. In Lee, for example, students can intern at the gallery (or at the adjoining Starving Artist Café or the nearby Spectrum Playhouse), in addition to taking part in the CIP curriculum.

The gallery and café and playhouse – which was formerly St. George’s Church – all contribute to the CIP’s integrated approach to helping its students transition to adulthood.

And the community benefits as well. “That’s one of the things I love about the way the gallery and the café works – it’s not this hard line,” said Steele. That artists who are not on the spectrum can show here – and artists who are. And they can all equally be involved with students . . . so I like the blend. I think it works really well for everybody.”

“Visions on the Spectrum II” and the work of the CIP point to the power of art not only to convey our inner experience, but to transcend and redefine the obstacles that stand between us. “What I love about looking at artwork like this – or anybody’s really – is how unique somebody’s perspective can be,” said Steele.

“And I think it gives a ray of hope to anyone who feels different, or maybe who has not found – or who is finding their voice or their way of communicating – to go for it and to really celebrate who they are.”

“Visions on the Spectrum II” will be on display at The Good Purpose Art Gallery in Lee, Mass., through January 2, 2013.