Arthur Miller's A View from the Bridge

A Stark Minimalist Production by Ivo van Hove

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 24, 2015

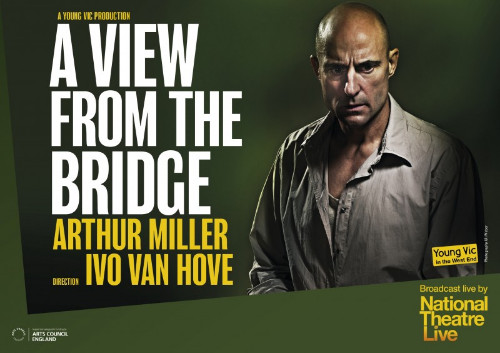

A View from the Bridge

By Arthur Miller

Directed by Ivo Van Hove. Set & lighting, Jan Versweyveld; costumes, An D'Huys; sound, Tom Gibbons; production stage manager, Martha Donaldson.

Cast: Mark Strong, Nicola Walker, Phoebe Fox, Russell Tovey, Michael Zegen, Michael Gould, Richard Hansell

Lyceum Theatre

149 West 45th Street

New York City

Perhaps you have previously seen Arthur Miller’s gritty 1956 drama “A View from the Bridge” and presume to know it. Why do we need yet another Broadway production since the successful one in 2010 by Gregory Mosher starring Liev Schreiber and Tony winning Scarlett Johansson?

In this centennial year of the birth of Miller think again.

When you come to this production directed by Ivo van Hove, with scenic and lighting design by his partner, Jan Versweyveld, leave all assumptions behind about Miller in general and this play in particular.

In a transfer to Broadway this stark, minimalist production won London’s Olivier Awards for best revival and best lead actor, Mark Strong as Eddie a taunt, primal and conflicted longshoreman. Another van Hove deconstruction of Miller, his iconic "The Crucible" opens for previews at the Walter Kerr Theatre on February 29.

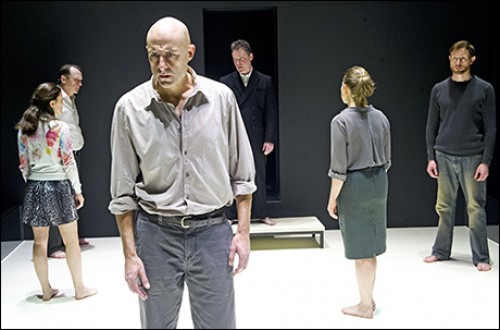

All of the realism of Miller, with sets, props and the ambiance of the harbor where Eddie, a rough Sicilian scratches out a meager living, have been stripped away. The play has been reduced to its narrative essentials. Short of performing with masks this is as close as it gets to classical Greek drama where much was left to the imagination and intellect of the audience.

Taking our seats, with my host NY critic Edward Rubin, we contemplated a large cube on stage flanked by rows of seating. In the sound design of Tom Gibbons the front wall is raised to a passage of Gabriel Fauré's Requiem.

There is a low wall surrounding the rectangle topped by a transparent glass fence. We see Eddie and a fellow worker Louis (Richard Hennsell), stripped to the waist, washing after a shift on the docks. This takes on a ritual intensity anticipating the literal bloodbath which rains down on a scrum of the cast in its gut wrenching climax.

The pace of the drama, particularly devoid of its props and illusions, is often slow and agonizing over the course of two hours in one act. The incremental passage of time is accented by a drum beat simulating an annoying dripping faucet. The tight, agonizing pace as the drama unfolds tests the limits of both physical and emotional endurance. It ends less with applause, and the now pro forma standing O, than a sense of relief.

Leaving the theater, however, is not the end of the experience which lingers and haunts us. We have seen van Hove reduce a classic contemporary play to its essence and revitalize it in a manner which opens up vast potential. It is so stark, simultaneously paradigmatic, ancient yet modern, that we have to mull it over and sleep on it. There are no easy conclusions about the shattering drama we have experienced.

With irony the play is as fresh as a ripped from the headlines take on the issue of aliens and immigration. Currently, America is roiled by reactionary discussion of sealing borders and rejecting possible terrorists among war torn Syrian refugees.

In the 1950s time frame of the Miller play the political agenda focuses on Sicilians smuggled in, defying stringent quotas and risking deportation to seek a better life in America.

The two illegal aliens, Marco (Michael Zegen) and Rodolfo (Russell Tovey) are cousins of Eddie’s wife Beatrice (Nicola Walker). There is marital tension about taking them in and providing shelter until they are on their own. Eddie is disturbed that this may stretch into months.

As a one man chorus Alfieri (Michael Gould), a neighborhood attorney and fixer, paces the perimeter of the set. When not speaking he perches on the wall and observes. Eventually he will enter the space from its rear door and elide from narrator to participant. Like the other actors he removes his shoes.

The costume designs of An D'Huys are intended to be generic and contemporary. Like the abstracted set the clothing makes no attempt to identify the era of the drama.

Stripping away potential distractions forces us to focus on the text and intellectual property of the play. Relentlessly, van Hove never lets us off the hook with even a hint of entertainment. Beyond Broadway van Hove evokes Parnassus.

This intense theatrical challenge entails complications. In a tightly wound, brooding and stoic performance we learn that Eddie, the tough-as-nails, lumpen proletariat is a Freudian mess.

Beatrice refers to his sexual estrangement. His excuse is the exhaustion of daily labor. There is little love, affection or physical attraction between them. They are together initially through vows and now just by habit. Dramatically it allows for arguing with and then turning on him. They have contrasting views of surrogate parenting.

In a very different mode there is volcanic eroticism when his adopted niece Catherine (Phoebe Fox) leaps up and embraces him. The director has him stroking her in a manner more lustful than familial. Only honor and duty restrain Eddie from ravishing her. This evokes a taboo sexual intensity that Beatrice is aware of informing her persona and subsequent actions.

As a guardian Eddie wants what’s best for his niece. He had paid for lessons at a secretarial school. But he is opposed to her working in an office on the docks. This will bring her into contact with the rough primal males he strives to protect her from. Catherine craves independence. Quitting school and taking a job is the first step toward earning money to leave home and find an apartment.

For Eddie this is a direct assault on his authority and manhood. We see him becoming unhinged.

In the form of the newly arrived and threatening immigrants, however, he must deal with the enemy within. Mario conveys coming to America and earning a decent living as a life and death challenge to save his starving family.

There is a similar tale from the blond and too handsome Rodolfo. Miller explains him as a descendant of Viking invaders of Sicily. Indeed the island was conquered by a vast range of ancient warriors from Normans to Muslims. So the handsome, blond, Sicilian Rodolfo is possible but not probable.

This casting makes the eventual romance between the handsome immigrant and naive, sheltered Catherine a bit too obvious. The vulnerable, inexperienced girl is an easy conquest for the excessively attractive and sophisticated Rodolfo.

Miller makes him something of a pretty boy who sings opera while working on the docks. This has earned the ridicule of fellow workers and exposes him to the risk of discovery by vigilant immigration authorities. It is essential that the illegals remain under the radar particularly during the daily shape up when crews are hired to unload ships.

Violence erupts when Eddie encounters Rodolpho and Catherine as lovers. He argues that Rodolfo is using her to get married as a path to citizenship. Given his looks, seductive charm and an apparent mismatch with Catherine, Eddie’s accusation is all too credible. Different casting would have made this essential plot point more compelling.

From this tipping point and its confrontation the drama catapults toward its devastating conclusion. In this trajectory the writing of Miller is too predictable. The tragedy lacks the reversals and discoveries required of great drama. There are few surprises in this production.

As deep as Miller delves is having Eddie embrace and kiss Rodolfo. Is this a Sicilian Il bacio della morte like the one Michael planted on Fredo in the Godfather? Has he marked Rodolfo for a hit? Or is it an outing of Eddie’s repressed eroticism? In his jealousy of Rodolfo as the lover of his niece does Eddie want in on the erotic action?

That takes some sorting out.

The intensity of rage and suffering leads Eddie to violate the Sicilian code of omertà. By turning rat he loses everything and is locked into a fatal conflict defending family and home. We see the machismo with which he is outmatched by Mario. While teaching Rodolfo to box he got in some low blows. But Eddie is defeated in a contest of strength with the tough and younger Mario. Again, Miller needlessly tipped his hand that physically Mario will prevail as the better man.

The finale of the drama is choreographed as high art. Again this is evocative of Greek tragedy in which all of the arts informed their dramas.

This production is likely to be recognized during the awards season. Initially, Strong was so tensely wound up and restrained that his explosions of eroticism and rage became all the more dramatically forceful. That in turn informed the finely tuned performance of Nicola Walker. It was such a delight to see the great British actress (M15, Last Tango in Halifax) on an America stage.

Of the two immigrants Zegen was credible in a way that Tovey was not. As Catherine the performance of Fox never reached its true potential. She lacked conviction and credibility as the sheltered teenager who rebelled against, and destroyed, her uncle.

Van Hove has encouraged us to reconsider not just Miller’s play but the entire spectrum of canonical contemporary theatre.