Tara Donovan at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

Ordinary Materials Equate to Extraordinary Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 24, 2008

Tara Donovan

Co Curated by Nicholas Baume and Jen Mergel

October 10 through Jan 4, 2009

Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

February 7 through May 11, 2009

Lois & Richard Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art, Cincinnati.

June 19 through September 13

Des Moines Arts Center

October 10, through January 16, 2010

There is an Aha moment when encountering contemporary art such as the exhilarating installation of work by Tara Donovan, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, 100 Northern Avenue, Boston, through January 4. It's a Gotcha experience where the artist uses simple and generic materials in such a masterful and exquisite manner, that we kick ourselves for not thinking of it first.

This is the frst museum survey of installations by Tara Donovan, a 38 year-old-artist who earned a BFA degree from the Corcoran College of Art in 1991. She shows with Pace Wildenstein Gallery in New York. Recenty she was named a MacArthur Fellow. Her ICA show has received rave reviews. It is a strong endorsement for the ICA which got off to a rough start with generally mediocre exhibitions during its first year in a stunning building with a dramatic waretfront location. Gradually the ICA is becoming an art world destination

The materials and concepts in Donovan's work originate in the early 20th century with the Readymades and Assisted Readymades of Marcel Duchamp. Imagine being among the first viewers to encounter such objects as "Fountain" (a urinal) or the "Bicycle Wheel and Stool." There was the predictable outrage, to the delight of the merry prankster and avant-garde master, as the public railed and ranted the mantra of why this had the nerve to be called art. It is an argument that has not subsided now more than a century later. I recall the challenge of convincing students that Duchamp was as important and influential as his peer Pablo Picasso. We had fun in my Avant-garde class debating the merits of John Cage.

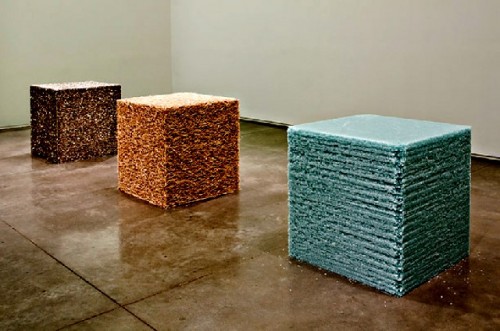

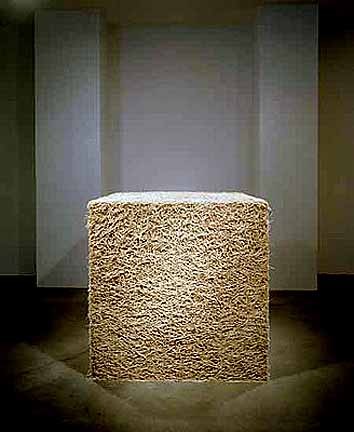

Outrage and tweaking the conservatism of the bourgeois appears to be an indispensable aspect of cutting edge contemporary art. But that did not appear to be an element in the obvious fascination and delight of fellow visitors during our tour of the delicious and delightful installation by Donovan at the ICA. There seemed to be no issue as to whether or not this was art. Rather there was a fascination with how it was made and the joyous discovery that such powerful and fascinating work was created with such ordinary materials as flowing oceans of plastic cups, compressed cubes of toothpicks, common pins and broken glass, stacks of buttons, floors covered with expanses of looped transparent tape, or a wall relief of thousands of stacked, drinking straws.

Of course, as with Duchamp, all of this is more as well as less than meets the eye. There is the short form, to discuss the materials and describe how they appear to the eye. The midbrow approach, to add a few fancy words and a dash of art speak just for cred. Or the full tilt boogie, academic discussion of post gender centered feminism, the epistemology of the proto visual, and tititubating tectonics of her practice with its assault on material culture, post colonialism, and the meltdown of globalization.

Through the daily use of Photoshop, and other computer programs, it has become the norm with a click of the mouse to perform image and editing functions that took days, weeks, and months in the pre computer era of the dark room or typewriter. Formerly, it might take an entire day to get a satisfactory print, through much calculation, trial and error. Today, we get a pleasing result by tweaking the contrast, color, and saturation functions in a matter of moments. Before our eyes we can dramatically change an image with seemingly endless options until it is just right. Similarly, with text documents there are endless options to change fonts and formats. The task of desktop publishing has become so routine that there are now blogs and websites in the zillions all pumping out an endless screed of content. In this environment virtually everyone is an artist, writer, and critic. The challenge is to choose where to focus our time and attention when faced with endless possibilities.

Is the day that far away when a computer can scan a published text and analyze its content, syntax, and vocabulary. You could then select from a scale of options calibrated to degree of difficulty. The lowest function, art for dummies, would break down the text in the most simple and generic terms. Rather like the reviews in your local daily and weekly papers. Often there is not the money or commitment for a full time art critic. So the norm is to take the museum or gallery press release, cut and paste, and maybe throw on an enticing headline. At the top of the scale, art for experts, would be a fully saturated article with all the art speak and epistemology. In general, several daunting concepts embedded in each of the individual sentences. The degree of difficulty in comprehending such a text is a measure of its value and insight.

It must be obvious to the reader that we should all aspire to the highest and most daunting levels of communication about art. The most absorbing book that dealt with this quest for intellectual perfection was Herman Hesse's final work "Das Glasperlenspiel" or "The Glass Bead Game." The protagonist became the master of the game but could not function in the real world. As one ascends into the stratosphere of a disciple there are fewer and fewer peers with whom to communicate.

In the intimidating world of contemporary art what you see is not what you get. As I stand before Donovan's compressed cubes of broken glass, tooth picks, and broken glass the experience seems simple, obvious, and delightful. It is right there in front of me and the eyes do not lie. The impact/ meaning is direct, visual, and palpable. There is that Aha and Gotcha factor; the sense of wonder and fascination. You notice that some toothpicks, pins, and shards of glass surround the base of the cubes. They have become detached as the cubes are held together by physical forces of what must have been enormous energy to compress them and the resultant static electricity. The objects, and their dandruff, also imply that they are fragile. The guards make a point of keeping you away from them. You wonder how they will be moved to the next museums in their itinerary. Or will they be recreated from a new mass of material? At the end of the show are all the cups, pins, and straws carefully packed and crated? Or, is it cheaper and more efficient to just trash the installation and start over?

This reminded me of a conversation with Chris Burden when he had a show at the ICA some years ago. He wanted to visually demonstrate the 50,000 tanks lined up along the border of the then divided Germany. He thought of various solutions including making model tanks; some 50,000 of them. It would have cost all of the money that he had at the time. He concluded that after the show they would end up in his garage. The solution was to visit a bank and for $4, 500 purchase 50,000 nickels. On top of a grid of these coins a team of installers placed one wooden match each with a dab of glue. At the end of the exhibition the coins were cleaned, rolled, and returned to the bank. It seemed brilliant that, other than an initial outlay to purchase the coins, he had created an installation that was virtually rent free.

Similarly, this Donovan exhibition was cost effective if you consider the materials. The intangibles are the sweat equity of the painstaking labor to assemble the installations. And, of course, how do you put a dollar value on an idea. What is an original Duchamp Readymade worth today? Of course, the interesting point here is that there are no originals. Initially, they had no dollar value and most of them were lost or abandoned as Duchamp moved about. Many of them were recreated and editioned when Walter Hopps gave Duchamp a retrospective in the 1960s. Until then Duchamp had "retired" and was devoted to becoming, as Hesse would posit, a Magister Ludi, or Master of the Game; in this case, chess. It is interesting to note that Duchamp became a moderately successful chess player but arguably the most influential artist of the 20th Century.

In the century since Duchamp we have a better understanding of the value of conceptual work involving generic, consumer items and industrial materials. While talk is cheap ideas are not. Consider the $7 million spent recently to create the Sol LeWitt installation of conceptual art, "Wall Drawings," which will be on view at Mass MoCA for the next 25 years. It is a yardstick to calculate the "value" of Donovan's work particularly in an environment where the status of an artist is measured by the market.

How I see and understand Donovan's work is limited. The physics of how the cubes stay together, or the algorithmics involved in configuring the straws, cups, and tape loops, are beyond my comprehension. There is that degree of difficulty issue. So I hover here between the experiential and the phenomenological. Hey, what else is new?