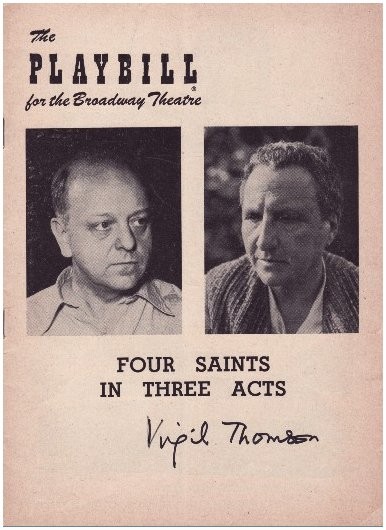

Four Saints in Three Acts

Intriguing Opera by Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thompson

By: David Bonetti - Nov 19, 2013

Four Saints in Three Acts

Music by Virgil Thomson

Words by Gertrude Stein

A Concert Performance

Boston Modern Orchestra Project

Jordan Hall, New England Conservatory

November 16, 2013

Conductor: Gil Rose

Chorus Master: Beth Willer

Cast: Charles Blandy (St. Chavez); Aaron Engebreth (St. Ignatius); Tom McNichols (Compère), Gigi Mitchell-Velasco (St. Teresa II); Sarah Pelletier (St. Teresa I); Deborah Selig (St. Settlement); Lynn Torgove (Commère)

“How many saints are there in it?” A very good question that recurs throughout the enduring Virgil Thomson/Gertrude Stein collaboration, “Four Saints in Three Acts.” In fact, there are some 20 (or so) saints in it, and while you were asking, which the text also does – “How many acts are there in it?” - there are four acts, and countless scenes as well, although the final act lasts only a blessed six minutes.

If you were expecting logic or rationality in Stein’s post-modern before-its-time world, you’ve come to the wrong place. The place is Avila, which is in Spain, but don’t expect any bullfights or glasses of sangria – although there is a sorta Spanish dance with castanets somewhere around the one hour mark. So, olé to you.

The 90-minute plus work is largely about its structure. Scene changes are sung, and we move from Scene Five to Scene Six to Scene Five again so many times we don’t know where we are. (We’re in Avila, remember? Except in Act II, when we’re in Barcelona.) Wittily, at a point when you might very well have had enough, Stein asks, “How much of it is finished?” You think, hopefully, that the end is in sight, but then it goes on and on for another half hour or so.

Space and time are both fluid, slippery as the post-modernists like to say. In the larger sense, the work is a meta-opera, about what an opera is rather than doing what an opera does. So, don’t look for a diva, although there are two singing the “starring” role of Saint Teresa. And don’t look for any big emotions – there are none. This is not “Tosca” after all. There is an emotional surge toward the end, which does not mark the end, but you sense it is intended to be more ironic – “this is what romantic opera does, but we, Virgil and Gertrude, are not doing” - than real.

But there are tunes to hum. “Four Saints” is a very hummable work, for a modern opera that is. In my mind, I’m humming “How many saints are there in it?” as I type. (But I have also been known when occasion calls to break out into “Lulu, mein engel” and that was by Alban Berg, a greater composer of a greater opera.)

If Stein practiced her idiot savant-like high modernism, which as I’ve suggested might really be post-modernism before anyone other than Marcel Duchamp had any idea what that might be, Thomson practiced a sort of back-to-roots American-scene tonalism. The opera opens with a real oom-pah-pah motif that sends the message that this is not something to fear, that it might actually be fun. His music is rolling, easy, full of church hymns and country dances that he might have picked up along the banks of the Missouri in his hometown of Kansas City. At one point the chorus breaks out in a spirited version of “My country ‘tis of thee” for no apparent reason.

And the work abounds in wordplay, rhymes out of the nursery or familiar today from hip-hop. There are tongue twisters that kept more than one singer following her score with (too) close regard.

There is no plot to speak of, although the BMOP program reprints the 1948 scenario dreamt up by Maurice Grosser, Thomson’s partner – we are allowed to say that now! Whoopee! It makes it sound kind of rational, but in practice it isn’t. I’ve seen it twice staged, the last time by Mark Morris, and there is no real story told, although it is far more entertaining to watch when there is something to see more than a line of singers at the lip of a stage, as there was in this concert version.

If ever a work needs to be staged to be enjoyed, this is it. In the original 1934 production, which took place at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, the sets were by Florine Steittheimer, an artist as hermetic as Stein, who created curtains made of cellophane, a material never previously seen on stage. Another original touch was the African American cast. Thomson insisted on using only black singers because of what he perceived to be their clear English enunciation and innocence because they lacked conservatory training. When the opera moved to New York City, where it was, believe it or not, a runaway hit, it proved to be the first Broadway show featuring an all black cast.

The fact that it played more than six weeks in New York suggests that even in 1934 there was a sizeable theater audience of gay men in that city. For above all, “Four Saints in Three Acts” is a high camp masterpiece. Think about it: a work ostensibly about two Roman Catholic saints, St. Teresa and St. Ignatius, written by a Jew and a mid-western Protestant, set to a nonsense text – St. Ignatius’s “big” aria is the famous “Pigeons on the grass, alas” – with an African American cast mooning around a set made of cellophane! It’s a wonder the morals squad didn’t shut it down on opening night. But it was so veiled, so refracted, that the cops couldn’t find anything wrong about it even if it was totally “wrong” from its opening chords. Let’s reflect a moment on what artistic genius has been lost with the opening of the closet. (OMG, is there any gay art anymore? Okay, Pet Shop Boys and Justin Bond, but not much else.)

The key to making “Four Saints” work is to treat 90 minutes of nonsense with utter seriousness. To Gil Rose’s credit, he succeeded at that, but still, it’s an awful lot of whimsy. (And I hate whimsy.) There is a lot of tail spinning to make the work stretch – Thomson wanted to make a full-evening work – and it sags in the middle. I remember getting bored at the halfway mark even in Morris’s inspired interpretation of the work as dance. A 45-minute “Four Saints” – maybe retitled “Two Saints” - would be more enjoyable.

The performance underscored the inherent musical weakness of a concert version of a work meant to be staged, which is supposed to be the concert version’s strength: Without the distraction of the stage-action - as if the very purpose of a work intended for the stage is a distraction - we can focus our attention on what is supremely important, the music. Although the orchestra played with sensitivity to Thomson’s easy mid-American rhythms, and the chorus sang with enthusiasm, the singers were glued to their scores to make sure they got all that complex word play right. If they had had to perform, they would have had to have learned their lines, and in the process of learning their lines, they would have learned the music more organically. It would have taken more time and it would have cost a lot more, but it would have resulted in a more committed performance.

Still, within their limits, the cast was largely excellent. Taking top honors was bass Tom McNichols as Compère, or Godfather, who sang with verbal fluency and beauty of tone. As St. Teresa I, Sarah Pelletier was also outstanding. Endowed with a high, clear, bright soprano she put her nonsense lines over with high seriousness. As St. Ignatius, baritone Aaron Engebreth sang with clear, open sounds, and he rose to the occasion of the immortal “Pigeons on the grass, alas.” The rest of the cast delivered what was asked, except for veteran mezzo-soprano Lynn Torgove as Commère, who was often inaudible – and I was sitting in the tenth row – and was glued to her score more than any of the other singers. (She did have some of the most complex tongue-twisters.)

Overall, the experience made me vow to boycott concert versions of operas in the future - except, of course, in the rare cases I need or want to go.