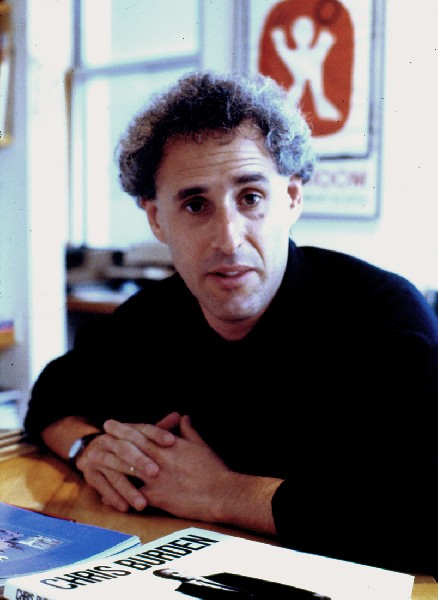

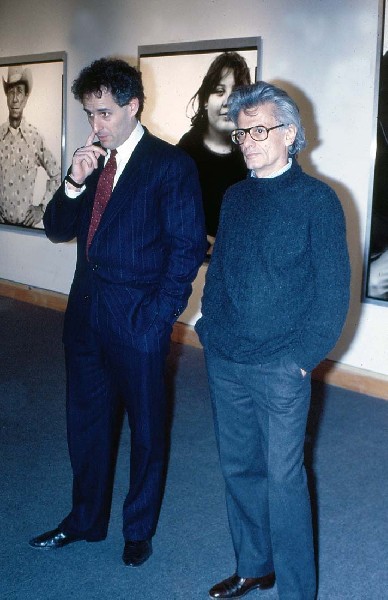

Former ICA and Whitney Director David A. Ross

Part One of a Feisty Dialogue

By: David Ross and Charles Giuliano - Nov 18, 2011

For nine years David A. Ross was the director of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston (1982-1991). That was followed as director of the Whitney Museum of American Art (1991-1998).

During a feisty and insightful dialogue he describes being seduced to head the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art at double the salary of the Whitney. It entailed the chance to build a great collection including works by Ellsworth Kelly, Robert Rauschenberg, René Magritte, Piet Mondrian, as well as Marcel Duchamp’s iconic “Fountain” (1917/1964). It was a decision which he came to regret in 2001.Ross describes his tenure in San Francisco as a “four year honeymoon followed by an abrupt divorce. I was fired.”

There were a number of projects since then. Currently he chairs the program of MFA Art Practice of the School of Visual Arts in New York City. He also is the lead singer for a band called Red comprising musicians he plays with in the vicinity of his home in Beacon, New York. It houses Dia Beacon the vast contemporary art museum which rivals Mass MoCA in North Adams.

Ross was particularly excited about the performance of his band that earned four encores during the recent ICA 75th Anniversary Benefit.

He earned a BS from Syracuse University’s Newhouse School of Communications but states that he learned “Nothing in school. Everything I know comes from working with artists. They have influenced what I see, what I read, and how I think.” Yet, for someone who got so little out of formal education, he has taught all through his career. Teaching artists has been rewarding because “They don’t put up with my bullshit.”

Nor does he suffer fools easily. During our dialogue, for example, he was pointed in commenting that over nine years at the ICA he regularly visited the Rose Art Museum and had a keen interest in its programming. But its director, Carl Belz, whom he views as a brilliant art historian, “Never once set foot in the ICA during my time there. He considered what we were doing not worth looking at. Artists who knew him described him as sitting in his office watching soap operas when not playing tennis.”

As a columnist for Art New England, as Ross put it to me during an interview at that time, “If Carl Belz spit in a bucket you would write an article about it.”

Of former Museum of Fine Arts curator of 20th Century Art, Kenworth Moffett, he recalled how he snubbed William H. Lane. It was only through Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr. “A first class gentleman whom everyone loved” that Lane and his wife Sandra gave the museum what is now the core of its great early to mid 20th Century collection of American Art and Photography. In 1988 Ross and his staff collaborated with Stebbins and Amy Lighthill to curate the American half of The BiNational: Art of the Late '80s in cooperation with the Stadtische Kunsthalle and the Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen of Dusseldorf.

Ross expressed contempt for the recent installation of the MFA’s Linde Family Wing of Contemporary Art. “Horrible. If that was done by a student of mine in a museology class it would be a C-.”

He has nothing positive to say about the Lord Norman Foster design for the Art of the Americas Wing. Particularly the waste of space of its enormous vaulted atrium and popular soaring glass sculpture by Dale Chihuly.

Asked about the Guggenheim he blasted former director Tom Krens as a “disaster.” He ridiculed his agenda of “branding” the Guggenheim through its creation of satellite museums. Ross feels that the museum may “never recover” from that dilution of its mandate. In general, he is opposed to museums endlessly expanding citing MoMA as an example. It is arguably an advantage for land locked museums like the New Museum, the new ICA, and the former Whitney under his watch. It forces institutions to work within their limitations. Responding to a comment that the ICA has no room to expand, and is isolated in its new location, Ross expressed admiration for the Diller and Scofidio design.

Like Kathy Halbreich, Ross went a long way for a museum professional with only an undergraduate degree. Arguably, he learned on the job starting as associate director, chief curator, University Art Museum, Berkeley (1977-1981); deputy director, curator of video art, Long Beach Museum of Art (1974-1977); curator of video art, Everson Museum of Art (1971-1974). All this led to his position at the ICA.

A selection of his exhibitions includes: Co-curator, "Tomorrow," Kumho Museum, Artsonje Center, Seoul and Long March Space, Beijing; "Peter Campus: A Survey," Antico Collegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City; "Lorna Simpson: 31," Claustro Sor Juana, Mexico City; "Quotidiana," Museum of Contemporary Art, Castello di Rivoli, Italy; "KoreAmericaKorea," Sonje Museum, Seoul; "Bill Viola: a 25 Year Survey," Whitney Museum of American Art, traveling exhibition: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; Museum fr Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Art Institute of Chicago.

When he was hired at the ICA Ross came with credentials as a curator of video art and new media. At the time he told me that “I didn’t come to the ICA to curate video.” At that point he stepped away from curating opting instead to support his staff. His one project at the ICA was a one man show and catalogue for Robin Winters who continues to be “a friend” and on Ross’s faculty at SVA. His only Whitney shows, largely by default, were for his close friend and former roommate, video artist, Bill Viola. Because of the illness of curator Walter Hopps he also stepped in on the Edward Kienholz retrospective. “Ed died (1994) during the project which also made it more complicated.”

We discussed museum deaccessions which in hindsight often resemble the Red Sox trading Babe Ruth to the Yankees. As he replied in 2009 to a blog by Richard Lacayo of Time Magazine “There is one more issue that no one seems to raise, regardless of which side of the issue is being argued. In my experience as an art museum director, the real deterrent should be simple humility — the assumption that acquisitions made in earnest by previous directors and/or curators should remain intact since the collection is the most important record of institutional direction and also functions as a significant historical index. Beyond this, all who have worked in art museums know that each curatorial generation reflects changing aesthetic priorities, and that none of us have access to an overarching truth. I would often ask myself, ‘how can I simply say that the judgements of previous directors were wrong and are now simply disposable?’ For it is this accretion of decisions that produce the aura that is a museum's reputation and constitutes such a large measure of its social value. Museums preserve not only objects, but the thinking that supports the decision that certain objects are worthy of perpetual conservation, study, and public display.”

While the ICA is now firmly established under director Jill Medvedow (with whom he agrees to disagree) when he arrived in Boston the ICA was on life support. It occupied a relatively small building awkwardly designed by the architect Graham Gund. The lower level was leased as a restaurant. There were times when Ross recalls that David Thorne, the chair of the board of trustees, wrote a personal check to meet payroll. “We were lucky to have 30,000 annual visitors” he said. Ross left the ICA nine years later with a $2 million endowment.

He felt that Boston needed to see a diverse range of American and international contemporary art. From this evolved the eclectic, chaotic Currents program. It was modeled after the seminal Matrix program started by Jim Elliott at the Wadsworth Athenaeum. Initially works changed at a random pace. That settled into increments with openings and specific time frames. Instead of publications there were small leaflets with notes on the works exhibited.

The mandate of Currents was to allow time to decide what was significant. The attempt was to convey an ever expanding thumbnail of what was going on. This was particularly important during a time when the MFA under Moffett was narrowly focused and Belz was "watching soaps at the Rose." It overlapped Kathy Halbreich at MIT and there were also fringe contemporary programs at the deCordova Museum and Sculpture Park in posh Lincoln, the Danforth Museum in Framingham, and The Fuller Museum of Art in Brockton. While they cobbled together aspects of contemporary art the ICA under Ross was the mover and shaker.

Taking over the ICA he kept in place the curators Jillian Levine and Elizabeth Sussman. Later Sussman joined Ross at the Whitney. Previously she curated mostly historical, modernist projects for the ICA, and underwent an extreme makeover. Ross hired David Joselit now a critic for Art in America and a professor at Yale. Along the way he promoted Bob Riley from installer to video curator.

It was a great and exciting period for contemporary art in Boston. Ross was always accessible and never failed to provide a lively, often outrageous interview. During our recent exchange Ross had his game face on.

David Ross I loved the idea that the ICA could get in trouble. Have its mouth washed out with soap. Could make friends and make enemies. Could be lovable and outrageous at the same time. It had a history of doing that. When David Thorne approached me at Berkley to take the ICA job it was basically with the idea that it could be reinvented. That was its primary quality that it remained open to being reinvented. I loved that idea about the ICA. That it was an institution open to reinvention. That’s what it was. I think it’s not that anymore. Not that I don’t like what it’s become but it’s not that anymore. Now it’s much more a formal institution.

When I first came it was very rangey. In the first couple of months we often couldn’t make payroll. David Thorne would write a check at the end of the week to help make the payroll. When I left there was an endowment of $2 million. Which was a lot. And a staff of close to 30. And the beginnings of a deal that would eventually bring it to the Fan Pier.

As well as international recognition for the first shows to look at a number of interesting and important areas. Including the Neo Geo and Appropriation movement. The first show to look seriously at Soviet Conceptual Art. The art which was being done in a period of transition and that show was done right before the end of the Soviet Union. At the time we didn’t know how close we were to that edge but that was a show I am very proud of. All the shows we did on the 50th anniversary. A series of shows I feel strongly about.

The ICA’s history is a rather remarkable one. For the 75th anniversary Jill (Medvedow) did this great slide show going all the way back with images of exhibitions and works of art that have been seen at the ICA from the 1930s to the present. It was just mind blowing. They are on the ICA website right now. You should take a look at it.

Charles Giuliano Perhaps I am in the minority but I find the building (by Diller and Scofidio) problematic. It is a sculptural monument from the exterior but not very pragmatic in its interior space. The ground floor has too much wasted space in the lobby. The area with a view slanting down to the water with rows of computer terminals is not used. The galleries for a growing permanent collection and storage are not adequate. It is locked into its footprint with no room to expand. Doesn’t that sound a lot like the Whitney’s issues which you faced?

DR There’s plenty of room to expand but that’s going to take a different time. They’ve just pulled off one miracle.

CG How would they expand? There is no vacant property surrounding the building that the ICA currently owns. Would they add above the roof? That disrupts the original design concept which was the case for the Whitney’s Breuer building that proved to be problematic as well as expansions for Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic design for the Guggenheim.

DR They might acquire more land in the area. Who knows? They’ll find a way. They are a long way away from needing to expand.

CG It’s also a remote location and takes a pilgrimage to visit.

DR It’s not so remote. They are in the future of Boston. Where they are is still to come. If you walk down Congress Street or any of the streets in the waterfront area they are jammed with tourists. Back Bay is kindah empty. All the hotels and all the restaurants and all the convention business. There’s just tons of people. The proof is in the pudding. They are generating huge numbers of people. They’ve had a million visitors since they opened. We were happy if we had 30,000 in a year. They’ve had a million visitors man. There’s the “ICA effect” as was said by the Boston Globe. “Boston’s changing and it’s the ICA effect” that’s what Sebastian Smee called it. The new MFA wing is a function of the ICA Effect.

CG Have you visited the MFA and seen the installation of the (Linde Family Wing for Contemporary Art).

DR Horrible. If that was done by a student of mine in a museology class it would be a C-.

CG Can you elaborate?

DR Do I need to? Do you think it’s good?

CG I’m asking you.

DR The artists whom I have talked to whose work is in there are just mortified. It’s so badly installed.

CG In what sense? Can you be more specific?

DR Physically and intellectually. It is horribly installed. Just terrible. They did a terrible job. I was excepting so much. I was so excited. Seeing what they spent so much money on I just can’t believe it. It is a long, long distance from the kind of trajectory I would expect from somebody like Trevor Fairbrother and Kathy Halbreich (1988- 1991, from MIT, before 16 years at the Walker Art Center, and now MoMA) starting that process. It was just terrible.

Quite frankly I’m not that impressed with the American wing (Art of the Americas) either. The old American galleries and the pre new installation, I loved it. I liked the object selections. I liked the graciousness of it. I felt (the new wing) was chopped up. And talk about wasted space. What the fuck is that giant space for? With a little restaurant in the middle of it! My God that’s pathetic. That atrium with a God damned Dale Chihuly in it. Oh my God. That’s supposed to be great? That’s one of the worst museum expansion spaces I’ve ever seen. That atrium is horrible. It’s a waste of space. An energy drain. An embarrassment. Physically it’s an embarrassing space.

CG I guess you don’t like it.

DR I was so disappointed. I was so looking forward to it. Whether or not I like Malcolm’s (Rogers director of the MFA) approach, his success as a fund raiser and bringing the profile of the museum up, making the museum a more popular attraction. Maybe I was expecting too much. Perhaps I am still square in the Ted Stebbins camp. (He departed for the Fogg Art Museum rather than accept an offer from Rogers to become chair of the Art of the Americas.)

Terrible.