Kandinsky at the Guggenheim Museum

50th Anniversary Exhibition Through Jan. 13

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 15, 2009

Arriving mid week we were surprised to find the line for the Kandinsky exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum, at 1071 Fifth Avenue in New York City, stretched around the corner.

There is a daunting degree of difficulty in the work of the Russian artist Vasily Kandinsky who was born in 1866 and died in seclusion outside Paris in 1944. While the artist lived through horrific events and endured personal tragedy, relocating several times because of circumstances of war and revolution, none of that is revealed in the content of the work.

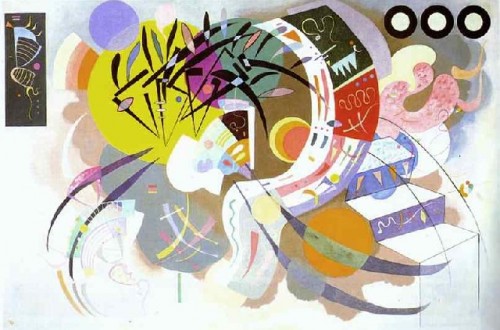

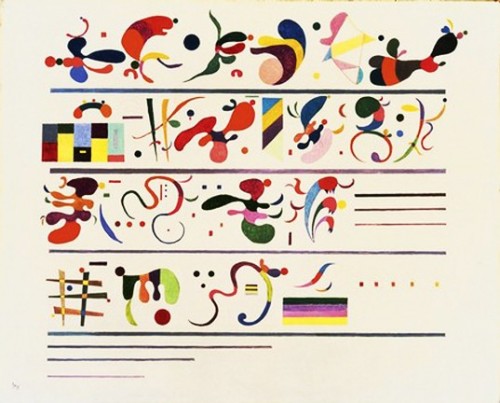

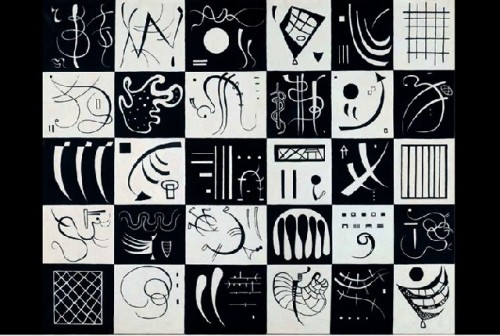

Even for the initiated who have encountered the work over many years it reveals its secrets in hard earned increments. It takes patience and careful looking. Only in the early phase of his work is there the entry portal of references to the landscape, nature, and the human experience. Rather early on he went beyond that and found equivalences between color, form, and music. He strove to conflate chroma and key. That notion was enforced by grouping his works into improvisations, or sketches initially inspire by nature, and the later resolution into compositions. As the work evolved it became ever more complex, structured and multi valent. It drew on a range of sources from the study of mystical philosophies to microscopic organisms and biomorphic shapes of the automatic surrealists.

In the spectrum of modernism in the first half of the 20th century he belongs to the handful of greatest and most influential masters. But, like Kasimir Malevich, Piet Mondrian, and Paul Klee he was devoted to pursuing art with the motive of pure visual research. He was to art what Einstein was to physics, Stravinsky and Schoenberg to music, Joyce and Beckett to literature and theatre.

While the School of Paris masters, Picasso and Matisse, pushed toward the limits of abstraction, they never quite abandoned nature or the figure. By 1911 Kandinsky came to reside there full time. Among art historians there is a discussion/ debate as to the first artists to create abstract or non objective paintings. These include the Czech painter, Frantisek Kupka, the Russian, Kasimir Malevich, as well as the American painters, Georgia O'Keeffe and Arthur Dove. On a different trajectory they were expanding the Cubism developed in 1907 by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Which was inspired by the late work of the Post Impressionist, Paul Cezanne.

When, after fleeing the rise of the Nazis in 1933, and the demise of the Bauhaus (the school is the subject of a concurrent exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art), Kandinsky and his (second) wife settled in the suburbs of Paris. There the artists he was most interested in were the surrealists, particularly Miro and Arp.

This exhibition is intended to be a part of the 50th anniversary of the Guggenheim museum which opened its Frank Lloyd Wright building in October of 1959. Recently, the museum completed extensive renovation to the structure with its unique spiral. Today it seems less so as there have been additions that open into more conventional exhibition spaces. But the primary and paradigmatic Guggenheim experience entails negotiating that imposing spiral which either impedes our slanted progress upward or compels us with ever greater speed and energy downward.

Generally we defy the design of curators by taking the elevator to the top of the museum and opting to work our way down through the exhibitions. Which means that you see them in reverse.

While this is the 50th anniversary of the occupation of its Fifth Avenue site its history predates that location. Much of what we see in the current exhibition, the collection's great depth in works by Kandinsky, results from the relationship between Solomon R. Guggenheim (1861-1949) and the artist Baroness Hilla Rebay von Ehrenwisen (1890-1967).They met in 1929 when she painted his portrait. She conveyed to him a passion for Kandinsky. In 1930 they met with the artist in his Bauhaus studio. Through Rebay he was encouraged to buy many works.

Guggenheim also bought works by Rebay as well as her protégée Rolf Scarlett. With Guggenheim's backing Rebay became the founding director of the Museum of Non Objectve Art in 1939. Following the death of her patron, in 1949, she was later ousted and the institution was renamed the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in 1952. It then expanded its mandate beyond Rebay's focus on abstraction. Her legacy survives in the great depth of works by Kandinsky. Occasionally the museum has shown works by Rebay, Scarlett, Rudolph Bauer and others in her circle. While interesting they prove to be minor and derivative. Rebay was also essential in the commission of Wright to design the museum.

Because the some 100 paintings in the spiral are installed in chronological order that meant that we started with the last works. Since they were the least familiar, complex, and absorbing this provided a remarkable experience and insight.

There were many surprises in discovering these late works. One feels familiar with the look and specifications of most periods of the oeuvre but that was not true for the late period. Here each meticulously crafted painting seems to pursue a specific notion. The palette is often soft with pretty pastel colors. There are all kinds of issues and ideas at play. In some there is an overall background color upon which there are figural elements. Other paintings are divided into zones of different color containing all kinds of elements. It takes time and concentration to decode and respond to what is going on. We found ourselves lingering through these works. These are paintings one would love to come back to over and over with the hope of extracting their complexity.

What most astonished me about those later works is how fresh and contemporary they felt. It is only now with computers that it is possible to emulate their design and imagery. One might imagine a geek figuring out the algorithms. I am sure that a wizard of computer generated graphic design would be able to create a program to construct similar work. The significant difference is that Kandinsky made these works by hand. That's why they are so astonishing.

As we reverse the spiral trajectory of the exhibition, traveling from last to first, it becomes obvious that there are aesthetic and personal threads. There was a clear focus and intention to his development. It is fascinating that his visual research with its limits and discipline ran parallel to the chaotic and catastrophic times that he lived through. At intervals through the exhibition, we come upon walls in which the biographical and historic events are spelled out. While the information is useful in understanding the persona, we are on our own connecting to the work.

Kandinsky's nonobjective paintings underscore the formalist notion that once they leave the studio they have a life and identity that is separate from the creator. We are meant to deal with the image and not look to the persona of the artist as a source for our understanding. Biography may offer insights to the work of some artists but with other artists it is a dead end.

It is on this line of demarcation that popularity tends to rise and fall. Even among critics work that is viewed as too cerebral and "inaccessible" is marginalized. The general public wants to feel their humanity expressed by art. We want to relate to the joy, tragedy, pain, or sensuality of the art. Without those connectors we are either lost or indifferent. Abstraction and non objective art is deliberately devoid of narrative. It appeals to intellect rather than emotion. It is about a visual experience. What is our emotional response to color, design, surface texture, material, scale, pattern and figuration? We are not encouraged to read the artist into the work but rather to view it on its own terms.

There is a popular perception that art owes us something. In the sense that van Gogh, as an art martyr, died for our sins as did Christ. There is well orchestrated empathy when we contemplate a painting by van Gogh. It is the romantic/ literary notion of art that we are eager to buy into.

But nobody raises these issues in areas of pure research. It would be absurd, if not demeaning, to demand that science or philosophy be more accessible. There is an understanding that the onus is on the individual to raise the bar. But when there was a week of the music of the composer Elliott Carter, now past 100 years old, at Tanglewood a couple of summers ago, critics who should know better, ranted and raved about the experience. Too few seemed inclined or capable of dealing with the music on its own terms.

At about the mid point of the Guggenheim's spiral there was a sense of familiarity about the paintings. From there down to the beginnings there was more of a sense of periods and grouping of the works. It seemed that the artist worked within a range of concepts and it was possible to focus on and track the progress comparing and contrasting one painting to others. One sensed the overall look of a Kandinsky particularly in the more rigidly formulaic compositions.

For reasons that I can't articulate, these mid career compositions are less engaging than the more freely gestural works that led up to them. The Munich, Blue Rider, works have been identified by the term abstract expressionism. That confuses it with the more common use of the term among New York School artists of World War II. The abstract expressionism of Kandinsky occurred, significantly, one World War earlier. They marked the end of his Munich period when, as a Russian, it was no longer safe to live in Germany.

He returned home in time to participate in the outbreak of the Russian Revolution. After a series of personal rebukes, and the death of his son, he left Russia with an invitation to join Gropius and the Bauhaus. His theories, practice and teaching were more in sync with the Bauhaus than the constraints of agit-prop which eventually resulted in the demise of the Great Utopia which slid into repressive Stalinism.

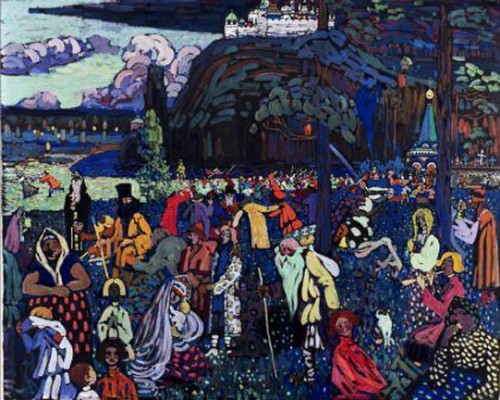

Reversing ourselves to the beginning of the exhibition there was a sense of joyous release in those initial works which drew on elements of Russian folklore, the broken brush work of impressionism, the later infusions of pointillism and the fauve.

With his mistress, the fellow artist Gabrielle Munter, from Munich they discovered the landscape of nearby Murnau. It was in these images that Kandinsky, on his own terms, repeated the research of artists from Picasso and Braque through Mondrian. But his notions of abstracting from nature don't pass through the prism of Cubism and its focus on Cezanne's dictum of the Cone, Cube and Cylinder. One does not see this geometry in those transitional works by Kandinsky. There is more of a sense of the late romantic and post impressionism; particularly in vibrancy and freedom from local color. Picasso's period of analytical cubism denies color in its concentration on form. Color did not return in Picasso's work until the period of synthetic cubism. Kandinsky by contrast never wavered from his interest in color and its equivalence of chroma and hue to musical scales.

In that sense one sees a cubist work by Picasso while we can hear and listen to a Kandinsky. When visiting this landmark exhibition, open your ears as well as your eyes. Try to hear the color. Such sweet thunder.