David Wilson Three

Folk Clubs of the 1960s

By: David Wilson and Charles Giuliano - Nov 14, 2010

Charles Giuliano How did military activation in the 1960s impact you?

David Wilson True to the law, Krohn-Hite kept me on the job for the six months required after return from activation and then let me go. It took me awhile to figure out that I was a pawn in a power struggle going on between George Hite and some of his department managers. I was at loggerheads with my test manager because I would not sign off on equipment specs that were different than those for which I had tested. He finally signed off on it himself and told me my days there were limited. George and I remained on friendly terms and our occasional if rare meetings were congenial.

CG What was the status of Broadside during your military activation and other employment?

DW During activation I came home in the evening and still had a hand in getting out the issues. The day Krohn-Hite let me go was the day that the first anniversary issue of Broadside came out. It was also the month that we had moved to new digs on Wendell St just off the Harvard campus. Money was tight. I collected unemployment for about two months.

Carl Bauer who had operated the Golden Vanity opened the Silver Vanity in Worcester, but it only lasted for a month or two. Worcester was not ready yet.

In May of ‘63, a pot bust at the Café Yana shut down the club and resulted in the arrest of newcomer John Hammond, Jr. The people involved in running the club sort of evaporated and dispersed. A few weeks later the club owner asked me if I would be interested in managing the club. I anguished over the offer, but finally accepted. I turned editorship of Broadside over to Jill Henderson and Lynn Musgrave, figuring that my continuing as editor would constitute a conflict of interests. Jill and Lynn put their stamp on Broadside and gave it a more professional look. I still contributed, mainly getting others like Tom Paxton, Casey Anderson, Peter LaFarge et al to contribute.

Running the Yana gave me a whole different perspective on the business. We were operating on a shoestring and barely making expenses, but we were building a good weekend audience and bringing in top acts, Pat Sky, Hedy West, Dave Van Ronk, Rev Gary Davis, Judy Roderick, The Holy Modal Rounders and Tim Hardin. We even lured John Hammond back. During their appearances, I put most of them up at my apartment which was a lifetime of experiences in itself.

I booked our biggest act to date, Jean Redpath, and it proved disastrous. JFK was assassinated (November 22, 1963) and the nation went into mourning. We stayed open, but attendance was sparse and we lost our whole nut and whatever bankroll we had built up.

(Another note of interest is that both Aldous Huxley and C. S. Lewis died that same Wednesday. It was a day indeed to mourn our losses)

CG That sounds devastating. How did the club manage after its finances were wiped out?

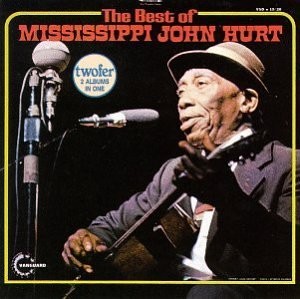

DW I managed to hold things together into January, but without front money for name performers it was nip and tuck. I was about to separate from the Yana all together when I was offered a great opportunity. I had the chance to book Mississippi John Hurt for his first Boston appearance. It was for a thousand dollars against half the house. To seal the deal I needed 500 up front. I brought the offer to the owner of the Yana, but he declined. A day later I went back and offered to rent the club from him for the week for a 100 bucks and he jumped at the opportunity. I started scrabbling for the front money.

Dick Waterman who had been writing for Broadside and hanging out at the Yana a lot offered to go halves with me and put up the front money. A week before the booking, Hurt appeared on the Johnnie Carson show and the publicity and word of mouth spread rapidly. We did three shows a night for five nights in February of ‘64 and turned away people at every show. It was the biggest success I ever had before or after and I do believe it whetted Dick’s appetite for the career he went on to carve out for himself.

CG What a windfall. It seems that it offset that prior disaster. Of course Waterman went on to manage legendary folk artists and was also the first manager of Bonnie Raitt.

DW While running the Yana I had started to manage a few performers including Ray Pong and Jerry Corbitt. The percentage I was making on their bookings and others kept me going. Most of the money I made on John Hurt I lost a few months later when I produced a Bukka White concert. Oh the follies of the entertainment industry. I had started writing again for Broadside and I was writing scripts on the spot for WGBH’s Folk Music USA.

Broadside took strong positions on the boycotting of ABC’s Hootenanny show for its blacklisting of Pete Seeger. Musicians lined up on both sides of the issue, with many of the mainstream pop folk groups claiming that by going on the show they could change the system from the inside. Some who clearly should have known better could not resist the lure of the big audience. Baez turned them down flat as did most of the musicians who had any political savvy.

In the first two years we had only published two songs, one by Dayle Stanley and one by Pat Sky. The last issue of Volume two introduced an ongoing column by Phil Ochs wherein he would introduce a song with a commentary on the background and his reasons for writing it. It was called “All the News Fit to Sing” and it paved the way for similar columns from Tom Paxton and Eric Andersen.

CG It seems that Broadside was expanding its presence in the music scene.

DW Well, it all seemed natural and obvious at that time. Singer/Songwriters were coming into their own. You know, at that time they were suspect, considered to be songwriters who could not get real artists to record their material, That seems strange today when most top artists write a lot of their own material.

In April of ‘64 I again took over editorship of Broadside. Mid month I got the word that Folk Music USA was being cancelled by WGBH. We printed a petition addressed to the program manager of the station. Whether it was due to our efforts, or not, the station got over 2000 protests within a few weeks. The show was renewed. Meanwhile, The Unicorn bought out Café Yana. They tried a variety of programming strategies to no avail and it closed before the end of the summer. Then the Unicorn announced the opening of a another site on Martha’s Vineyard not far from the Mooncusser. The Beatles arrived in NY and dominated the pop music scene. Radio Caroline, the UK’s first pirate radio station, began transmission and the Boston underground was abuzz with plans to launch a similar station off the coast of Massachusetts. The Rolling Stones released their first LP that April. The Who started breaking guitars on stage, the Kinks released their first album and 3000 Berkley students blocked a police car with an anti war activist under arrest. This was the start of the Berkley Free speech movement. Folk musicians were in the vanguard of civil rights and antiwar activities and though not as well remembered now, the plight of the Appalachian miners. Companies of Black and White performers were touring the south performing in unsegregated venues, mostly churches, campaigning for voter registration and peaceful resistance.

Over the summer the civil rights movement continued to heat up. In Mississippi Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney were murdered and their bodies found a month later. Casualties in Vietnam began to pick up and Johnson fabricated the Gulf of Tonkin incident as an excuse to escalate US involvement. All the warnings and rants I had been shunned for over the previous two years became a simple matter of fact. The John Birch Society was waxing in strength and supporting the Goldwater presidential campaign. I went off to my summer reserve meeting at Otis AFB and was working in the CO’s office. The chatter in the unit among the mission officers was all jingoistic. We were running simulation bombing runs of Cuba, and we were encouraged to vote for Barry Goldwater so we could go bomb the hell out of Fidel. In the middle of it all I scooted off for a weekend at the Newport Folk Festival. Talk about something completely different.

Pot busts had become so common that they no longer made the news. LSD, Mescalin, Psilocybin, MDA, Speed, Cocaine and Heroin were all on the increase. Each drug had its apostles and demonizers. It was clear that drugs were making a lot of people very wealthy.

Silly as it may seem now, and tedious as it was then, was an ongoing dialogue/diatribe in our pages trying to figure out just what was and what was not folk music. Critics, fans, performers, academicians all wrote pieces for us espousing various points of view. Looking back now I can see that this deeply divided perspective was fundamental to our eventual foundering, but mid ‘60s the passions stirred by the issue kept people involved. And just like now, it was not the sane, rational voices that received the attention of most readers, but the extremists on both sides. “Commercial” was a dirty word even though we were pouring money on those we favored for whatever reason we favored them.

In October, with each issue containing more and more national advertising, Broadside moved out of its editor’s apartment, (in this case, mine) for the first time and into an office at 145 Columbia street where it remained for the rest of its life. This was mostly due to the efforts of Bill Rabkin who had come on board as Business Manager earlier in the year and through whose efforts economic viability seemed attainable. And the staff continued to expand as well with over 20 names on the masthead, all volunteers.

But I made two errors of judgment that year that still have me shaking my head at how foolish I could be. I had a spat with Dick Waterman over deadlines that ended up with him walking out creating a breach in a friendship that has never been healed. The second was the result of a three week jaunt to Berkley and returning to find that someone on the staff had committed us to a new series of columns on protest singers. I do not know now what I found so egregious in the first two installments, but I cancelled the column and earned the enmity of its author. His success was, I am sure, sweet revenge, as Jon Landau went on to become one of the most respected music writers of the period. What was I thinking?

When Johnson won in a landslide it was a relief, but a mixed blessing and, in truth, things were just about to heat up for real. But, I’m sorry, I got distracted there for a bit. Still, the music, the events and the lifestyle was all intertwined and each element strongly influenced the others.

CG Can you elaborate on the clubs of that era?

DW During the first half of that decade there was a curious split delineated by the river. My intuition is that it originated during the rise and fall of The Golden Vanity (Near Boston University). That split seemed to have been created more by fans and club management than by the artists. Most of the performers worked wherever they could, whenever they could, with some consideration given to pay scale and schedule. Boston and Cambridge never had the “pass the hat clubs” that made up such a large part of the Greenwich Village scene. The Vanity as well as The Gallery, on Hemenway Street, and The Salamander, on Huntington Ave, all became victims of urban renewal at about the same time as the construction of the Prudential Center and the Turnpike Extension. Café Yana dodged the construction moving from Beacon Street over to Brookline Ave, just about the same distance outside of Kenmore Square but still in easy reach of the BU student population. In a way, the split may have just been mirroring the rivalry between BU and Harvard.

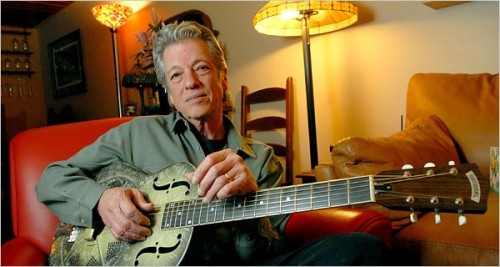

And as it developed, some musicians came to think of themselves as “Charles Street Performers” and resented what they perceived as snubbing coming from across the river. I recently got an email from one of those performers and in it he characterized himself thusly… “I was a proud member of the Charles St. Folk scene. The blue collar folk scene, not to be confused with the elite of Cambridge. LOL.” To this day, probably the most enduring graduates of Charles St are Chris Smither and Bill Staines. One might, however, make a case for Noel Stookie who often played on Charles St and who donned the role of Paul in Peter, Paul and Mary.

In Harvard Square, Club 47, and Club Jolly Beaver, waxed as Tulla’s Coffee Grinder waned. Boston coffeehouses were strung out in a line along the river with a cluster around Beacon Hill. A fancy new club opened on Hancock Street but was short lived. Charles St had the Turkshead where the legendary Rudi Vanelli had performed, The Orleans, and The Loft. The Unicorn sat across from the rising Prudential center on Boylston Street a block from Pall’s Mall and the Jazz Workshop. Café Yana held down the western end of the line. One other coffeehouse that had a reasonable life span was, The Rose, in the North End. In the latter half of the decade as folk rock and psychedelic bands came and went followed by the rise of the Blues Bands, we saw larger venues come into being. The Boston Tea Party, The Ark, The Psychedelic Supermarket, and in Allston, The Crosstown Bus.

On the North Shore, Howard Ferguson had opened the King’s Rook coffeehouse in Marblehead and a few years later added a second and larger venue in Ipswich where they presented local area and national performers. Worcester briefly had the Silver Vanity, Springfield had the Pesky Serpent, Martha’s Vineyard spawned the MoonCusser, the Unicorn II and a third club whose name I cannot remember. Hyannis had the Ballad & Banjo and the Carousel.