Met Returns Tut Objects

Agreement Between Museum and Egyptian Government

By: MET - Nov 10, 2010

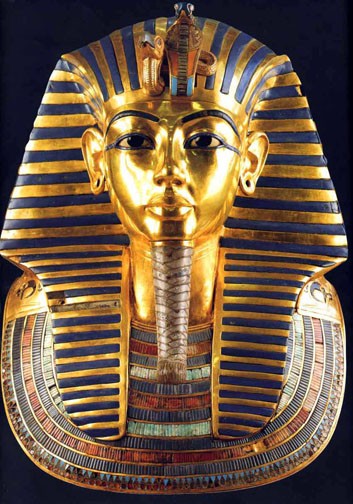

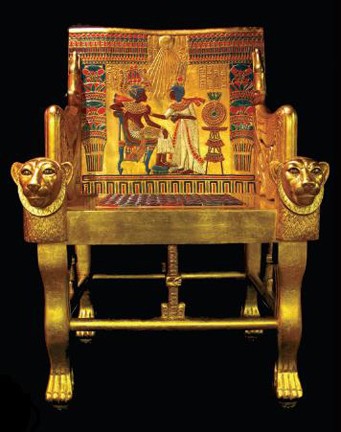

Thomas P. Campbell, Director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Zahi Hawass, Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities of Egypt, announced jointly today that, effective immediately, the Museum will acknowledge Egypt’s title to 19 ancient Egyptian objects in its collection since early in the 20th century. All of these small-scale objects, which range from study samples to a three-quarter-inch-high bronze dog and a sphinx bracelet-element, can be attributed with certainty to Tutankhamun’s tomb, which was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922 in the Valley of the Kings. The Museum initiated this formal acknowledgment after renewed, in-depth research by two of its curators substantiated the history of the objects.

Mr. Campbell stated: “Research conducted by the Museum’s Department of Egyptian Art has produced detailed evidence leading us to conclude without doubt that 19 objects, which entered the Met’s collection over the period of the 1920s to 1940s, originated in Tutankhamun’s tomb. Because of precise legislation relating to that excavation, these objects were never meant to have left Egypt, and therefore should rightfully belong to the Government of Egypt. I am therefore pleased to announce—in concert with our long-time colleague Zahi Hawass, who has contributed so greatly over many years to the recognition and preservation of the historic treasures of Egypt—this formal acknowledgment that title to the objects belongs to Egypt.”

“This is a wonderful gesture on the part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” said Zahi Hawass. “For many years the museum, and especially the Egyptian art department, has been a strong partner in our ongoing efforts to repatriate illegally exported antiquities. Through their research, they have provided us with information that has helped us to recover a number of important objects, and last year, they even purchased and then gave to Egypt a granite fragment that joins with a shrine on display in Luxor, so that this object could be restored. Thanks to the generosity and ethical behavior of the Met, these 19 objects from the tomb of Tutankhamun can now be reunited with the other treasures of the boy king.”

Dr. Hawass also announced that the objects will now go on display with the Tutankhamun exhibition at Times Square, where they will stay until January 2011. They will then travel back to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they will be shown for six months in the context of the Metropolitan Museum’s renowned Egyptian collection. Upon their return to Egypt in June 2011, they will be given a special place in the Tutankhamun galleries at the Egyptian Museum, Cairo, and then will move, with the rest of the Tut collection, to the Grand Egyptian Museum at Giza, scheduled to open in 2012.

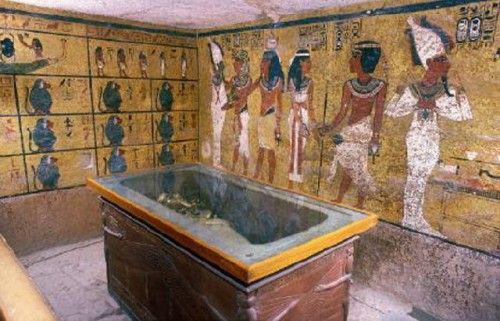

At the time that Howard Carter and his sponsor, the Earl of Carnarvon, discovered the tomb of pharaoh Tutankhamun (reigned ca. 1336-1327 B.C.), the Egyptian government generally allowed excavators to keep a substantial portion of the finds from excavations undertaken and financed by them. However, during the decade that it took Carter and his team to recover the thousands of precious objects from this king’s tomb, it became increasingly clear that no such partition of finds would take place in the case of the Tutankamun tomb.

Owing to the splendor of the treasures discovered in the tomb, conjectures soon started nevertheless, suggesting that certain objects of high quality, dating roughly to the time of Tutankhamun and residing in various collections outside Egypt, actually originated from the king’s tomb. Such conjectures intensified after the death of Howard Carter in 1939, when a number of fine objects were found to be part of his estate. When the Metropolitan Museum acquired some of these objects, however, the whole group had been subjected to careful scrutiny by experts and representatives of the Egyptian government; and subsequent research has found no evidence of such a provenance in the overwhelming majority of cases. Likewise, thorough study of objects that entered the Metropolitan Museum from the private collection of Lord Carnarvon in 1926 has not produced any evidence of the kind.

The 19 objects now identified as indeed originating from the tomb of King Tutankhamun can be divided into two groups. Fifteen of the 19 pieces have the status of bits or samples. The remaining four are of more significant art-historical interest and include a small bronze dog less than three-quarters of an inch in height and a small sphinx bracelet-element, acquired from Howard Carter’s niece, after they had been probated with his estate; they were later recognized to have been noted in the tomb records although they do not appear in any excavation photographs. Two other pieces—part of a handle and a broad collar accompanied by additional beads—entered the collection because they were found in 1939 among the contents of Carter’s house at Luxor; all of the contents of that house were bequeathed by Carter to the Metropolitan Museum. Although there was discussion between Harry Burton (a Museum photographer based in Egypt, the Museum’s last representative in Egypt before World War II broke out, and one of Carter’s two executors) and Herbert Winlock about the origins of these works and about making arrangements for Burton to discuss with a representative of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo whether these works should be handed over to Egypt, that discussion was not resolved before Burton’s death in 1940. When the Metropolitan Museum’s expedition house in Egypt was closed in 1948, the pieces were sent to New York.