Boston Lyric Opera's Flawless Madama Butterfly

Yunah Lee Soars as Butterfly

By: David Bonetti - Nov 09, 2012

Madama Butterfly

by Giacomo Puccini

Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa based on a play by David Belasco

First performed La Scala, Milano, 1904

Boston Lyric Opera

Shubert Theatre

Nov. 2, 4, 7, 9, 11

Conducted by Andrew Bisantz

Stage director: Lillian Groag

Set designer: John Conklin

Costume designer: Marie Anne Chiment

Lighting designer: Robert Wierzel

Cast: Yunah Lee, Cio-Cio San (Butterfly); Dinyar Vania, Lt. B.F. Pinkerton; Weston Hurt, Sharpless; Kelley O’Connor, Suzuki; Michael Colvin, Goro; David Cushing, the Bonze; Nicole Rodin; Kate Pinkerton; Daxton Cochran Jesser, Sorrow; David Lara, the Imperial Commissioner; Thomas Oesterling, the Official Registrar; David McFerrin, Prince Yamadori

Opera sophisticates tend to groan at the prospect of another Puccini production, unless it is a rarity like La Fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West) or features a cast of superstars. (Sorry, folks, Luciano Pavarroti is dead and Monserrat Caballe is retired.) I have to admit that I fall into that category, and I was less than enthusiastic about a Boston Lyric Opera production of Madama Butterfly without any singers with above-the-title billing.

Boy, was I wrong. A good Puccini production makes you understand why his popular trio – La Boheme, Tosca and Madama Butterfly – are programmed so frequently. They are damn good, that’s why. Musically ravishing, intensely dramatic, quintessentially romantic, they pull on your heartstrings and tear ducts in equal measure. Tragic love and untimely death are their currency. There is a reason why they have been the bread and butter of opera companies of every level of sophistication since they premiered at the turn of the last century.

But when the production is not just good, but nearly flawless like the BLO’s, it reminds you that Puccini is more than just a skilled tear jerker. He is a genius of dramatic and musical aptness and concision. In none of his great works is there an extraneous moment, a wasted note. Two and a half hours of such focused emotional intensity should be too much to handle, but instead his works fill audiences with joy, a hard-won joy that emerges from the sorrow inherent in the stories they have just heard. The Greeks called it catharsis.

The fact that the BLO had a superb cast of singers committed to making this familiar work fresh, headlined by the astonishing Butterfly of American soprano Yunah Lee, made that joy all the deeper.

Madama Butterfly is perhaps Puccini’s most difficult work for modern audiences to take. There are always grumblings about his female characters – that they are victims, that they all end up dead at the end. To an extent that is true. He was a fin-de-siecle man in the era of the femme fatale.

Mimi in La Boheme dies in the last scene, but she is a victim of tuberculosis, a common scourge of the time that took in their prime men as well as women, and before that she lived an ordinary enough life for an impoverished young seamstress in Paris who is prone to fall in love.

Tosca kills herself after her lover is shot in what she thought was a mock-execution, but if she didn’t, she certainly would have been killed by the Roman constabulary for murdering their chief. In other words, she takes control of her life and chooses death by her own means rather than give in to political victimhood. And the role she plays is that of a glamorous, self-actualized opera singer, who is used to getting her way.

Cio-Cio-San, however, is a victim and a naïf, an unrealized character who rises to self-knowledge only when she kills herself in order to preserve her sense of honor.

Another obstacle for at least American audiences is that Pinkerton, the man who loves Butterfly and leaves her to her delusions, is presented as a cad who takes what he wants unconcerned with the mess he leaves behind. The opera has frequently been presented as an allegory of American Imperialism; the fact that it is set in the port of Nagasaki often exploited, sometimes cheaply. To make his point clear, that he is dealing with a particular kind of American cluelessness, however, Puccini wove motifs from the “Star-Spangled Banner” into his orchestral tapestry to represent Pinkerton.

That the story is about two unequal lovers doesn’t keep it from hitting all the romantic high-notes. In an emotionally complex performance like the one Dinyar Vania gave for the BLO, you believe that Pinkerton does love Butterfly, at least when he is with her. Indeed, the love duet that closes Act I, “Viene la sera” (Night falls), is one of the most ravishing in the literature. But isn’t that the way of all cads, whether they are from a land far across the sea or the boy next door?

Like most of Puccini’s most popular works, Madama Butterfly is a melodrama raised to the level of real drama by the passionate music Puccini wrote for it, here full of motifs and melodies from the Japanese tradition. The plot is simple, but the emotional nuances Puccini wrought from it are not.

In brief: Cio-Cio-San, Butterfly to her friends, is a 15-year old geisha who is sold as a wife to an American naval lieutenant, B.F. Pinkerton. He loves her in his own way; she gives herself to him totally, converting to Christianity and forsaking her family and tradition. He leaves, promising to come back, not knowing that Butterfly is pregnant. Butterfly waits, even though her maid Suzuki, the American consul Sharpless, and Goro, the marriage broker who originally made the match between her and Pinkerton, all urge her to forget him and move on.

Pinkerton does come back, three years later, with his American wife. They want to take his half-American son, which is the opera’s big false note – Americans at the time didn’t acknowledge their mixed-race children. Butterfly hands over the boy, whom she has named Sorrow, and then kills herself in a ritual Seppuku, singing, “Who cannot live with honor must die with honor,” realizing at last that she was just a kept woman in Pinkerton’s eyes, not a real wife. The music for her suicide is one of the great dramatic scenas in all opera.

The BLO production is convincing from the directorial conceit of a mimed suicide of Butterfly’s father to its devastating end, Butterfly twitching on the floor, her white robe dyed blood red by Robert Wierzel’s brilliant lighting.

Key to its extraordinary success is a cast, production team, and orchestra that are together at every moment. The cast lived their characters, and if the Pinkerton of Dinyar Vania is a little stiff, wasn’t Pinkerton, the quintessential American jock, himself a little stiff?

One got the sense that the cast rehearsed with stage director Lillian Groag much longer than the norm – or that she was able to achieve remarkable effects with miraculous efficiency. It seemed that every interaction was choreographed to perfection. (Groag’s direction of Agrippina two seasons ago was similarly detailed. One hopes she is coming back.) One example: when Butterfly’s family learns that she has converted to Christianity, denouncing the traditional gods, they turn on her as one, bending at the waist, pointing to her in accusation, sighing collectively with the orchestra, backing out of the room and out of her life. Groag makes a scene that might be played as a minor moment– it lasts just a minute or two – terribly moving.

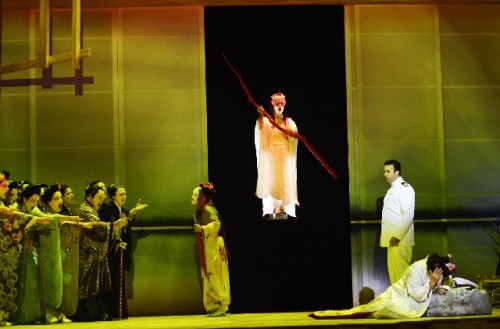

Groag’s addition of a number of silent visions proved to be problematic with other critics, but I found them dramatically justified. I already mentioned the scene before the overture when Butterfly’s father is seen committing seppuku, prefiguring her own. Most controversial was the interpolation Groag made when Butterfly is singing, “Un bel di vedremo,” her great aria of faith in Pinkerton’s return, looking as she is wont from her hillside villa to the harbor. Indeed, I can understand those that think that moment, the greatest single aria in the opera, need not be augmented. It doesn’t. But having Pinkerton enter, casually smoking a cigarette, at the moment Butterfly sings, “I will see him walking up the hillside,” made vivid the visualizations of her desires. And the scene of her and Pinkerton in their American dining room cutting the birthday cake of their American son, now a young teen, breaks your heart at the delusions she harbors of future happiness.

The rest of the production cast worked as one to achieve a cohesive vision for the opera. John Conklin’s sets were simple and evocative. Marie Anne Chiment’s costumes were right on, the kimonos the women wear and their parasols pastel visions of elegance. Lighting designer Robert Wierzel made both costumes and set work. When Butterfly has retired to her dressing room to prepare for her first night with Pinkerton he pours on blue light to represent the approach of dusk and then bathes Pinkerton in his white navy uniform in bright white light, creating an indelible image of a man callously awaiting his prize. In the flower scene, when Butterfly and Suzuki decorate the house with flowers in anticipation of Pinkerton’s return, he bathes the stage in a mauve light that creates a lovely palette for the giant red flowers that descend from above. And at the end, the red light he pours on the dying Butterfly gives the love-death a properly bloody conclusion.

High praise goes to Andrew Bisantz who led the orchestra with real verve and power and worked with the singers so that there was unanimity of understanding.

Puccini’s operas are fail-safe, but they really take-off only if they have singers who can put over their roles vocally. The entire cast was excellent if not stellar. None of them will be singing at the Met or at Covent Garden soon – their voices are too small. But the Shubert Theatre is a small theater and their voices were perfectly attuned to its scale. What’s more important than voice size was the fact that the cast possessed voices well suited to Italian romanticism and that they knew their roles inside and out. And they sang – and acted - well together, no one voice outclassing the others.

Dinyar Vania, who has sung Puccini roles in small houses, is a fine Italianate tenor - a treasure in the opera house these days - hitting all his high passages effortlessly, and singing with a fullness throughout his range. He played the callow lieutenant with appropriate cluelessness until the final scene when he realizes what he has done.

As Suzuki, Kelley O’Connor, was the best singer of the evening, a real dramatic mezzo with a rich deep voice that melded beautifully with Butterfly’s during her big moment in the flower duet. As Butterfly maintains her delusions in the face of reality in the last act, O’Connor’s twice-intoned “povera Butterfly,” were heart breaking. O’Connor also stood out last season in Opera Boston’s Beatrice et Benedict, the final production of that missed local company.

Baritone Weston Hurt sang the unshowy role of the American consul Sharpless, who grows increasingly concerned with the delusions the young former geisha, with appropriate gravitas.

The rest of the cast was fine, with nods of approval toward tenor Michael Colvin as the venal marriage broker Goro, and bass-baritone David Cushing, who made his moment as Butterfly’s cousin, the angry priest named the Bonze, memorable.

All productions of Madama Butterfly soar or crash depending on the performance of its central character. Fortunately for the BLO and for Boston opera audiences, Yunah Lee’s Butterfly soared into the stratosphere even as she lay dead on the stage as the final percussive chords of the orchestra mark her death, Pinkerton’s desperate calls of “Buttterfly, Butterfly” facilitating her escape from earthly disappointments.

Lee has made the role of Butterfly her specialty and it is one for, if not the ages, our age. Possessed of a small but pleasant voice, she is able to grow into dramatic soprano territory without forcing when she has to, but she excels at the smaller quiet moments that define, in her interpretation, who this Cio-Cio-San is. No one would confuse her Butterfly with that of Renata Tebaldi or Maria Callas, but that’s okay. No one would confuse their Butterflys with hers.

Her entry scene is extraordinary. As she and her entourage approach the house Pinkerton has rented for them, they sing like the murmurs of the breeze in the trees as Sharpless describes it. The door opens and a dozen women in kimonos twirling umbrellas float in as if on that breeze. At last Butterfly appears in the doorway, dressed from head to toe in white, a bride ready to give herself to her husband. She enters the house on an apparent cushion of air.

A tiny woman, Lee plays Butterfly like not only the child she is but like a doll. She eventually grows to acknowledge her situation, but she remains that doll. She is no avenging angel like the Butterfly Catherine Malfitano played in a controversial production from a decade and a half ago.

What’s extraordinary about Lee’s performance is not so much the singing, although that is all you could wish for, but her acting at the micro-level. Every movement, every gesture is not hers, but Butterfly’s. Lee has internalized the role like few other actors I have seen. She reaches the peak of her interpretation in the moments that lead to her ritual suicide. Understanding finally her situation and fate, she asks Suzuki for her obi, her wedding gown. In the stark white gown, her hair down, she goes into a state of being that is rare to witness on the stage. Every movement is a poem. Time seems to stand still and space evaporate. There is just Butterfly and her destiny. I can recall few other singers who were able to create such moments of total fusion of movement, sound and meaning – Magda Olivero, Anja Silja, Shirley Verrett, Lorraine Hunt. (Alas, I never heard Callas live.) All had greater – bigger – voices than Lee, but she has learned the lesson of all great singing actresses – to be present in the moment.