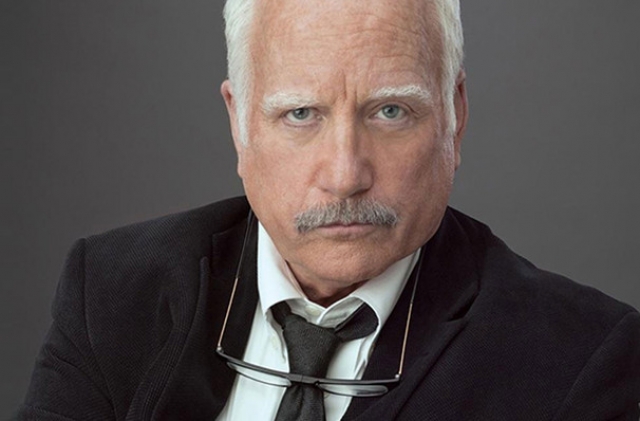

Relativity at TheaterWorks Stars Richard Dreyfuss

St. Germain Play Asks Can a Great Man Be a Good Man

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 07, 2016

Relativity

By Mark St. Germain

Directed by Rob Ruggiero

Set design, Brian Prather; Costumes, Alejo Vietti; Lighting, Philip S. Rosenberg; Sound, Michael Miceli and Lucas Clopton

Cast: Richard Dreyfuss (Albert Einstein), Christa Scott-Reed (Margaret Harding), Lori Wilner (Helen Dukas)

TheaterWorks, Hartford, Conn. Through Nov. 20

For the past two years Mark St. Germain has been included in the New York Times list of most produced American playwrights.

His latest play, Relativity, was commissioned by the Florida Studio Theatre where it premiered in August. With a different cast, starring Richard Dreyfuss as Albert Einstein, it has opened the 31st season of TheaterWorks in Hartford. Productions in Iowa and Illinois are scheduled and there are ongoing negotiations for possible venues.

The marquee appeal of Dreyfuss has resulted in a sold out run in Hartford that has been extended through November 20. The opening night performance in the intimate and well appointed theatre with 200 seats was well received with a pro-forma standing ovation.

There is much to like about the play that has a well crafted, taut and insightful script. It has been aptly directed by Rob Ruggiero who is the artistic director of the company. The production values are superb including an evocative, cozy set, the home/ office of Einstein designed by the estimable Brian Prather. It has many period touches and a window from which the renowned scientist can gaze out at the FBI agents who keep watch and pick through his trash for incriminating documents.

We learn that during the era of McCarthyism he was suspected of being a communist. He avowed pacifism and deplored racism. Einstein had conflicted positions about how his theories led to the nuclear age.

The play evokes the paranoia that surrounded Einstein (1879-1955) who left Germany for Princeton in 1933. He joined the Institute for Advanced Study and lived there for the remaining twenty-two years of his life.

The premise of this drama explores whether a great man is also a good man.

We first encounter Dreyfuss coyly playing the cuddly, eccentric public perception of Einstein. It reflects the populist need to humanize men of genius who are beyond our comprehension. As St. Germain researched Einstein he uncovered a man who really didn't like to be with other people.

This is revealed during a visit by an ersatz reporter, Margaret Harding (Christa Scott-Reed). Initially Einstein is accessible and charming. We are amused to see him telling jokes to a parrot in a covered cage.

The easy banter soon grows darker as the reporter asks ever more probing and personal questions. She reads him quotes from her research as well as excerpts from numerous interviews.

In a reversal he asks "Is this an interview or an interrogation?"

The intensity ratchets up as we learn that the reporter may indeed be the abandoned daughter he fathered with his abused first wife Mileva Mari Einstein. She gave birth in 1902 at home with her family and he never saw the child. Researchers differ on what became of her after 1904 including that she may have died of scarlet fever. Or in this drama that she was adopted and as an adult learned the identity of her birth parents.

The ever evolving and encroaching exchange is fascinating and brilliantly written. This play stands with St. Germain's best work. It is fair to predict that it will be widely produced by regional theatres.

This is, however, a less than definitive production.

As a remarkably skilled actor Dreyfuss has created a credible portrait with adept gestures and a convincing German-inflected accent. But the dynamic of his responses to the ever sharper probing of Scott-Reed fails to develop with conviction. The arc of conflict lacks precise calibration.

Part of the disconnect comes with casting. The Einstein of Dreyfuss is short, disheveled (with that signature wild hair) and vulnerable. His alleged daughter towers over him. That presents an obvious visual mismatch. There is an escape line when he says that she clearly takes after her mother. We have no way to fact check her physical presence.

There is the matter of motive. Why has she made such an effort to research and confront him? Effectively he thrusts this back at her. What does she want from him?

A widow she reveals that her son is a prodigy with an IQ of 190. He has earned early admission to Princeton but she refuses to have him meet his grandfather. Is this protection for her son or punishment of the father who abandoned her? What part does revenge play in the hypothetical meeting?

The third person in the drama is his housekeeper Helen Dukas (Lori Wilner). She was devoted to his every need after Elsa (his cousin and second wife) died in 1936. There is implied intimacy but no obvious affection. He demanded a woman who provided service as well as services with no expectations.

It is precisely the contract he had with Margaret's mother. She recites the humiliating terms to him. After several years he gave Mileva a list of rules. If she wanted to remain married she could not talk to him. She was to leave three meals a day in his study. She was never to criticize him and he could sleep with somebody two nights a week.

His sharp retort to Margaret is that she demanded the money from his Nobel Prize as alimony.

He probably loved her when they met as students. Margaret alleges that she played a role in his early research. In a letter he said to a friend that "She wants one thing out of life and that's to be Mrs. Albert Einstein." From the first day she called him "The Great Man."

As Margaret charges in his private life Einstein was a 'monster.' Helen, who became his sole heir (disinheriting Hans and Edward), responds that he is a 'good man.'

Arguably, the man of genius was a philanderer, misogynist and misanthrope who stated that "Every human relationship I have is a chain around my neck."

St. Germain creates reasonable doubt about Einstein's assertion that's what it takes to change the world.

A version of this review previously was posted to Boston's The Arts Fuse.