Guggenheim Bilbao at Twenty

An Inspiring Success Story

By: Zeren Earls - Nov 06, 2017

The Guggenheim Museum Bilbao recently concluded a year-long celebration of its 20th anniversary under the concept “Art Changes Everything”, inspired by the major changes that the city of Bilbao and its residents have experienced since the Museum opened on October 19, 1997, while at the same time underscoring the transformational capacity of art. The Museum has played a catalytic role in the urban and economic regeneration of Bilbao, a former industrial city in the Basque region of northern Spain, which I enjoyed visiting in September.

Included in a visionary urban plan laid out by the Basque administration, the Bilbao Museum was targeted to be one of the international constellations of the prestigious Guggenheim brand, by agreeing to invest locally in an art collection that would at a minimum match the cost of the building, to be paid for by the Guggenheim Foundation. Also, as part of a larger action plan for urban regeneration, the building for the Museum would be designed by world-renowned architect Frank Gehry, paving the way for other important projects by leading international architects, including Norman Foster, Arata Isozaki, Rafael Moneo, and Cesar Pelli, and creating a new Bilbao.

In twenty short years the city of Bilbao has become a twenty-first century city, without losing its essence, by transforming formerly run-down areas around the Nervion River, which is now the main axis of the city, enjoyed by tourists and locals alike. Gehry’s building sits on a 32,500-m2 site, one side of which runs down a ramp to the river, 16 meters below the rest of the city. Another side is intersected by the Puente de la Salve bridge, one of the main access roads to the city. Overcoming these problems successfully, Gehry’s design integrates the building into the city’s urban structure, occupying the center of an imaginary triangle formed by the Fine Art Museum, the University of Deusto and the Arriaga theater.

The building has the presence of a huge sculpture of interconnecting shapes set against the backdrop of the river, the city center and the slopes of mount Artxanda. Rectangular limestone blocks contrast with curved and bent forms covered in titanium, with glass walls providing light for the building. The limestone structure blends in with the sandstone façade of the university in the background, and “fish-scale” titanium panels cover most of the building, giving it an attractive rough look. The stone, titanium and glass curves have been designed with the aid of computers.

The open-air terrace of the Museum is a spectacle of outdoor site-specific works, such as Fujiko Nakaya’s Fog Sculpture # 08025, Yves Klein’s Fire Fountain, Maman by Louise Bourgeois and Puppy by Jeff Koons. A stainless-steel sculpture, Puppy charms with its coating of live flowering plants due to an internal soil and irrigation system. Also by Koons Tulips, the most recent site-specific acquisition and the most exuberant of them all, is installed at one end of the terrace along the Museum’s riverside façade. The stainless-steel sculpture with a transparent color coating is shaped in the form of a bunch of seven tulips more than five meters long. The flower forms, each with a brilliant glossy finish reflecting a colored light, are placed horizontal to the ground, where their stems weave and intersect. The playful spirit of this piece is carried to the Museum’s gift shop as a glittering image on T-shirts.

One-of-a-kind spaces within the Museum complex also feature site-specific works such as Richard Serra’s The Matter of Time, Jenny Holzer’s Installation for Bilbao and Daniel Buren’s Arcos Rojos, the latter conceived specifically for the Salve Bridge, which Gehry integrated into the building’s design. Serra’s gigantic corten-steel piece invites the public to participate by walking through its curvaceous forms, while other visitors get a bird’s-eye view from an upper level.

The Bilbao collection has a unique identity in that it only acquires pieces which complement the collection of the Guggenheim Foundation. Currently the collection comprises a total of 130 works by 74 artists from the second half of the twentieth century up to the present day. The works, displayed in chronological order, start on the third floor and wind their way down the floors of the building. The exhibition “Masterpieces from the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao Collection” highlights the most representative pieces in a permanent space on the third floor.

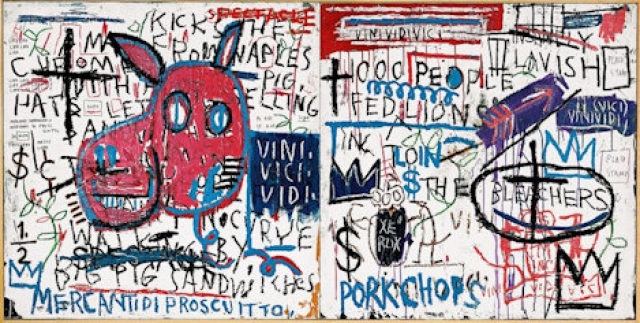

Among the most important works of this exhibition is Mark Rothko’s Untitled (1952-53); Large Blue Anthropometry (ca 1960) by Yves Klein; Barge, a silkscreened painting (1962-63) by Robert Rauschenberg; Nine Discourses on Commodus (1963) by Cy Twombly; and One Hundred and Fifty Multicolored Marilyns (1979) by Andy Warhol. Works by Basque masters Eduardo Chillida and Jorge Oteiza provide a reference to post-war sculpture. The showcase includes important works by German artists Anselm Kiefer and Gerhard Richter, as well as Americans Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Third floor galleries take us through the late decades of the twentieth century, moving away from conceptual and minimal art to highlight the return of painting, as exemplified by the work of Majorcan artist Miguel Barcelo. His work, Flood (1990), is presented as a gray landscape, created by making cuts in the surface of the canvas and applying an abundance of paint. Mrs. Lenin and the Nightingale (2008) by Georg Baselitz presents an upside-down portrait of Lenin and Stalin, alluding to the history of the artist’s native East Germany, while highlighting German neo-expressionism.

A significant group of canvases make up Mother’s Room (1995-97) by Italian artist Francesco Clemente. Commissioned by the Museum, this work evokes the decorative murals of Renaissance palaces, while at the same time depicting deformed, contorted or transformed figures against these riotous floral backgrounds, inviting the viewer to sort out the symbolism of the work.

A return to figuration and expressiveness in art is featured in the works of American artists Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Schnabel uses a wide variety of materials, including the written word, to weave narratives in works like Fakires (1998) and Spain (1986). Basquiat’s Man from Naples (1982) reflects the artist’s feelings of resentment toward a wealthy Italian patron. Most of the pictorial surface is taken up by a chaotic jumble of scrawls, words, numbers, symbols and colors, reminiscent of graffiti.

The second floor of the Museum is devoted to temporary exhibitions with international impact, while the galleries on the first floor focus on the latest trends in contemporary art. Also on this floor is the Film and Video Gallery, which at the time of my visit featured Bill Viola: A Retrospective, a major thematic and chronological survey of the artist’s career as part of a twelve-month program for the Museum’s 20th anniversary celebration.

Other featured exhibitions for the anniversary included “Heroes” by Georg Baselitz and “The Guests” by Ken Jacobs. The former was devoted to a series of paintings of defeated “heroes” by the German artist, the latter to a 3D film in black and white and color, created by distorting an original film by the Lumiere Brothers, the fathers of cinematography, and resulting in a hypnotic presentation of moving images. Works by artists who were born or worked in the Basque Country were also included in the celebration through a juried selection.

The combination of Gehry’s signature sculptural building, a permanent collection whose value has increased sevenfold since the initial investment of 110 million euros and an ongoing ambitious program of exhibitions has attracted nearly 20 million visitors to date from all over the world, with two thirds coming from outside Spain. Over the last 20 years, the Museum has contributed almost 4 billion euros to the national GDP and has maintained an average of 5,000 jobs in the region.

May the Frank Gehry building now planned for a museum in North Adams, Massachusetts play a similar catalytic role in bringing about an inspiring aesthetic and economic miracle. However, as the Bilbao model shows, a signature sculptural building must be part of a larger urban design and cultural investment if it is to inject the tremendous amount of life hoped for in the area.