Museum of Fine Arts Boston Growing Pains

Special Exhibitions: Assyrian, Karsh, Whiteread

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 05, 2008

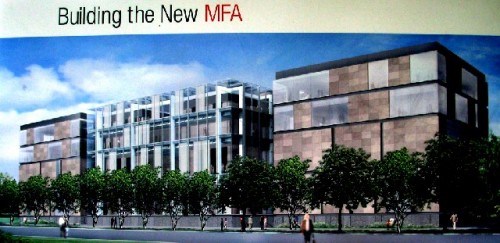

Approaching the Museum of Fine Arts Boston the new wings appear to be taking shape. Despite being under construction through 2010, for the most part, it was business as usual. Already aspects of the Lord Norman Foster design and master plan are completed. The former gallery for the Lane Collection of the 20th Century American Arts has been renovated as a handsome and efficient reception area. There are several monitors for self guided digital tours of the collections and exhibitions.

A friendly guard, who recognized me from years of taking gangs of students through the galleries, asked where we had been? He urged us to check out the new Fenway Entrance including two monumental bronze sculptures of baby heads by the Spanish artist, Antonio Lopez Garcia.

Once more the MFA is being torn apart and put back together again. The last time according to an I. M. Pei design when the European Paintings galleries were climate controlled and a new wing was added. This occurred under the watch of former director Jan Fontein.

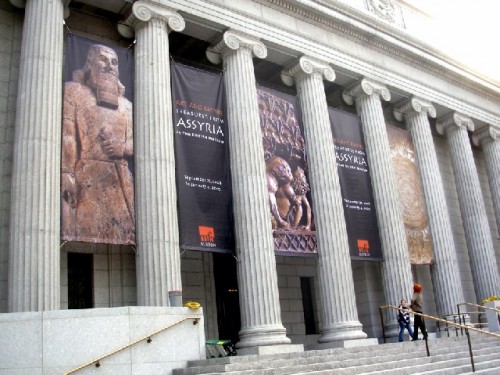

Although many permanent collection galleries are closed there was a full menu of enticing special exhibitions which remain on view through January. Not to be missed is a spectacular survey "Art & Empire: Treasures from Assyria in the British Museum." We will discuss this in a separate review. It includes unique works which we have never seen during visits to the British Museum. It is a Special Exhibition in every sense. There is a small but choice selection of photographs in "Karsh100: A Biography of Images." On view is an installation by "Rachel Whiteread" the British artist, as well as, a gallery of related works. On November 19 (through May 10) the MFA launches the new Herb Ritts Gallery which is devoted to photography. For its first exhibition "Photographic Images" there will be many recent acquisitions.

Long admonished for being stodgy and conservative in the area of modern and contemporary art and photography, with dramatic new space under construction, the MFA appears to be addressing this lapse with energy and commitment. The museum founded its Department of Contemporary Art in 1971 with the appointment of Kenworth Moffett as its first curator. At the time, curator of American Art, Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., quipped that the museum was making a commitment to the 20th century "Â…now that it is nearly over." But the program for modern and contemporary art, until now, has faired poorly gaining mostly apathetic and mixed reviews. Moffett was narrowly focused on collecting formalism and Color Field Painting. It is an interest that has lapsed although the MFA has this work, patricularly by Morris Louis, in great depth. Of course, today, Moffett's acquisitions would be viewed quite differently had the Board of Trustees, on the recommendation of the short termed director, Merrill Reuppel, not turned down Jackson Pollock's masterpiece "Lavender Mist." The painting was quickly snapped up by the National Gallery.

The contemporary curators who followed Moffett have been less than stellar. In an utter disaster Amy Lighthill took over. She is now out of the field. Alan Shestack, the director at the time, lured Kathy Halberich from MIT. She stayed too briefly before moving on as director of the Walker Arts Center and is now a co director of the Museum of Modern Art. Her second in command, Trevor Fairbrother, moved up a slot but never really grew into the position. It was widely viewed that Malcolm Rogers squandered an opportunity when he appointed Cheryl Brutvan. While she did his bidding, and played along with the program, Brutvan never established a strong identity or point of view.Her exhibitions and acquisitions were not up to the standards of a world class museum. Brutvan is leaving the museum after her final show "Whiteread" with "no immediate plans."

In Brutvan's defense it was well known that several high profile candidates turned down the position. The modern/ contemporary program was identified as the Cinderella of the MFA with little or no collection, space, or budget. Plus, as proved to be true, the contemporary curator would have to deal with Rogers who fancied himself as knowing a thing or two about contemporary art and show biz. That devolved into shows of "Wallace and Gromit," "Herb Ritts" "Karsh" "Guitars" "The William I. Koch Collection" (with his yachts on the front lawn) and the "Cars of Ralph Lauren" to mention just a few of the vulgarian offerings. What the future holds remains to be seen. But don't hold your breath. Having missed the boat on the 20th century it is not too late to do a better job with the art of the 21st century.

Growing pains, however, are nothing new for the MFA which remains one of the world's great museums, in the U.S., second only to its rival and nemesis The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The MFA was founded in 1870 and the Met in 1871. Since then they have been the museum equivalent of the Yankees and Red Sox.

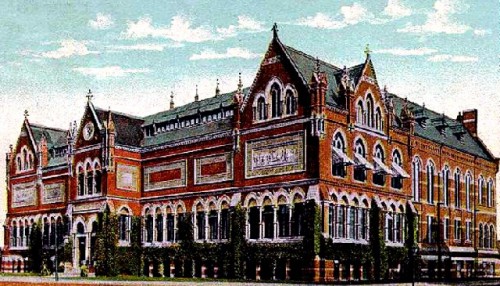

Originally housed in a Venetian Gothic building by Sturgis and Brigham, in Copley Square (1871-1878) the building was razed and replaced by the Copley Plaza Hotel. The valuable property was sold and the MFA moved up Huntington Avenue to its present location on the Fenway. The monumental classical building, designed by Guy Lowell (1870-1927), was constructed between 1906-1909. Following I.M. Pei, Lord Norman Foster is the third major architect to alter the footprint of the MFA. It is safe to predict that, when the construction is complete, the MFA will greatly increase its international status.

Although controversial and unpopular, he fired or pushed out many senior curators, it is arguable to state that the British born, Malcolm Rogers (1948), who came to the MFA in 1994, will be remembered as its greatest and most dynamic director. After the mediocre regimes of Jan Fontein and Alan Shestack the MFA was on the ropes. In the quid pro quo gamesmanship of dealing with other museums for loans and special exhibitions the MFA had become a second tier player.

Initially, with a poor hand to play, Rogers made unpopular staff and budget cuts. With little money for special exhibitions Rogers focused on recycling the permanent collection. When I brought this up during an interview Malcolm, with some pique, responded that "Charles, I assure you that I will not be dragging things up from the basement." Eventually that was true but not at first. Today, he can point to the current "Assyrian" exhibition in conjunction with the British Museum. In March, the MFA is partnering with the Louvre to present "Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese: Rivals in Renaissance Venice." That's not chopped liver. Surely, Rogers plans many spectacular surprises with the relaunch of the renovated museum in 2010.

Between now and then there is much to see and enjoy. Part of the strategy of special exhibitions is to court acquisitions. Koch, is not much of a collector, and the exhibition was a laughing stock. But Koch is as rich as Croesus and Malcom likes to follow the money no matter where it leads him. Karsh and Ritts are mostly considered to be commercial photographers. But they have bequeathed to the museum major works and resources.

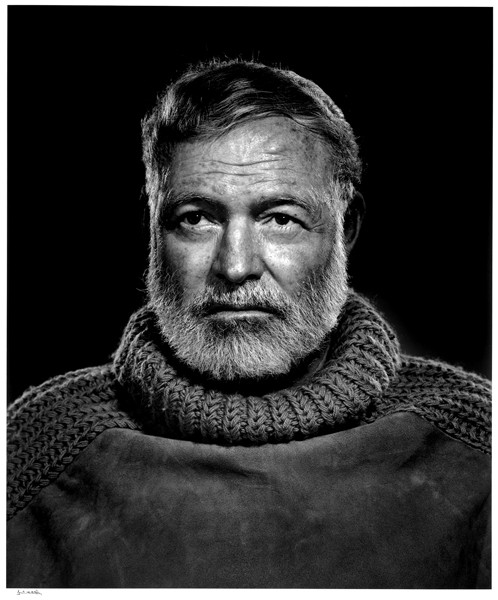

I met Yousuf Karsh in the 1960s. Or, should I say, he stumbled onto me. He was visiting the MFA to photograph then director, Perry T. Rathbone. While he was exploring the museum, including its basement, he appeared at the door of the Egyptian storage where I worked as an intern. He was very curious about the inner workings of the museum and I took him on a brief tour. Not long after there was the first Karsh show at the MFA followed by several more.

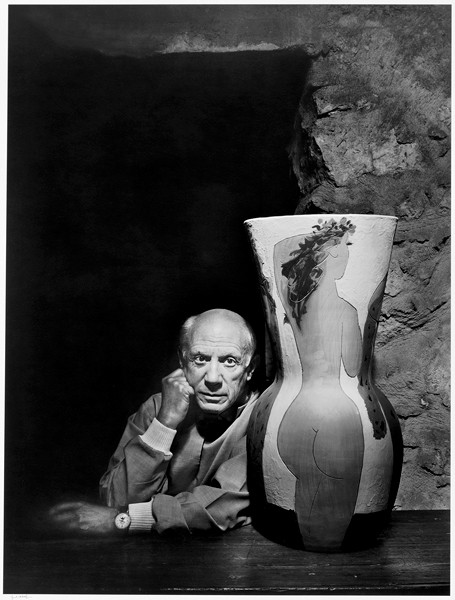

By now those Karsh images are readily familiar. They are portraits of the famous and powerful, not as who they were, but as how they would want to be seen and remembered. The portrait of Winston Churchill seems as rigid and scowling as a sculpture in bronze. Karsh is always content to present the façade and never penetrates beyond the surface of the sitter. Everything is just skin deep but with remarkable lighting and textures. The portrait of Ernest Hemingway is iconic but we get little sense of his hard drinking, macho, sexist personality. Karsh has Picasso peeking out from behind one of his painted pots. It tells us little or nothing about his enigmatic personality. More successful, perhaps, are his images of women. The portrait of Audrey Hepburn is elegant and beautiful. We encounter the sensuality of Anita Ekberg but never really get close to Jackie Kennedy in a formal gown. As an artist friend commented he was amazed at the wrinkles in the face of the poet W.H. Auden. It was Karsh's job to make these celebrities look good but in the process we gain few insights about them or their photographer.

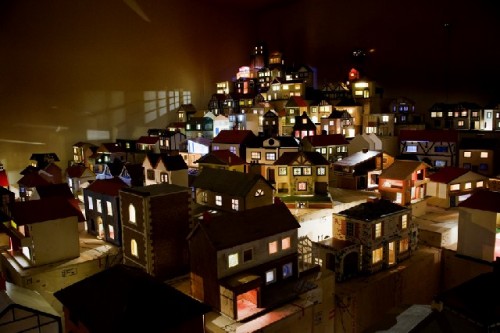

Some years ago Milena Kalinovska introduced Bostonians to the British artist, Rachel Whiteread, in an exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art. In one gallery of the old ICA on Boylston Street the artist installed a full scale plaster cast of a room. It was a daunting and confounding project. We have seen the work on many occasions since then often with variations of casting objects, great and small, in a variety of materials. In the current project for the MFA, Whitehill has created an installation of an ersatz village, rising up low hills, using found doll houses she has collected in recent years. The gallery is dark and illuminated by lights within the houses.

As an exhibition, the Whitehill installation failed to hold our attention beyond a few minutes. It didn't take long to "get it" and then what? This work too vividly reminded me of windows in department stores decorated with Christmas villages, or a visit to the old F. A. O. Schwartz toy store. Since then, I have grown up, so this work by Whitehill seems rather puerile.

By then it was time for tea. And to talk about that magnificent Assyrian exhibition. But, that's another story.