Cecily Brown at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston

If painting is dead do we need another hero or heroine?

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 05, 2006

Cecily Brown

Organized by the

Curated by Jeff Fleming

October 18 through

Catalogue: With essays by Fleming, Linda Nochlin and Linda Norden, 80 pages, illustrated. Published by the

Recently all the big guns of contemporary art criticism have been mustered out to blast away on the topic of the death/ rebirth of painting. For all of the regular pronouncements of the "death of painting" it just refuses to roll over and play dead. Painting as possum. Not dead but just pretending to be as it gathers strength for yet another resurrection. The chest beating and Tarzan "King of the Jungle" yowls have focused on the Brice Marden (Born 1938) retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art and, to a lesser extent, on Cecily Brown (born 1969) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The same folks who lined up to heap praise and accolades on the marginal Elizabeth Murray when she showed at MoMA are now reaching down ever deeper for even more bombastic pronouncements. While Murray was generally regarded as one of the best painters of her generation the New Yorker, for example, has upped the stakes by dubbing Marden as the best abstract painter of the past forty years which is a double dip of generations. One way of enforcing that statement has been the approach of simply documenting the real estate of various Marden studios and pied a terres which range from

Or, to a somewhat lesser degree the MFA, through

If you are of a certain age, I was born in 1940, you grew up with painting in art school. More like the post abstract expressionism practiced by Brown than the austere work of Marden which evolved after we emerged from the academy. In particular, I remember being both attracted and repelled, seduced and annoyed when viewing the early works of Marden, the grayish, monochrome, small, horizontal paintings with that narrow edge of drips on their bottoms when they were shown at Bykert Gallery on 57th street. Then and now I feel that they are his best works. I recall the handsome artist and his wife Helen when they would sweep into Max's Kansas City generally earlier than Andy and his entourage which arrived after midnight and sat in that back room under the Dan Flavin sculpture. So there was always glamour about the artist.

Deep down we all love painting. Museums are full of it. Until Duchamp, after the success of his "Nude Descending the Staircase" in the 1913 Armory Show, declared that painting was "too retinal" and developed the Ready Made, Found Object and Assisted Ready Made. He was right of course and painting should have died back then. With an appropriate gangster's funeral, lots of big bouquets and wreaths of flowers and a mile long procession of limousines and cars to the grave site in

Under such a curse, burden and inflated responsibility how can any artist just paint? But the cause is great, noble and worth the risk of failure. Mostly critics are willing to put on their blinders or look the other way when in the presence of "great painting." These are the same critics and curators who are savage in denouncing paintings which do not live up to their esoteric standards. The usual line is that painting is dead and most art sucks but so and so is really terrific because I know and am saying so. Most times they get it wrong like Elizabeth Murray and Ellen Gallagher for example. Bad painting. Well, not really bad, there is so much that is worse. Let's just say boring.

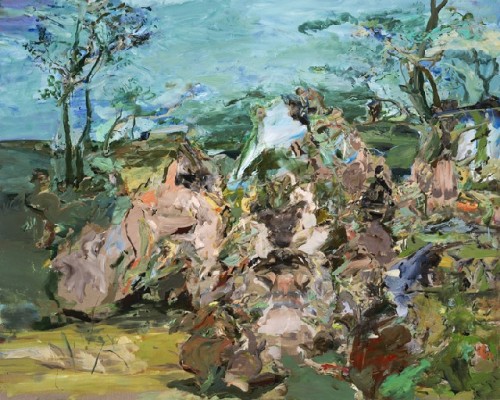

I really, really, really tried to like the Cecily Brown show at the MFA. In the past I have always been excited and anxious to see more when one of her works would appear in large mediocre surveys like "Greater New York" at PS1. In such a field of wannabes her work is always riveting and outstanding. Seeing her work one on one with time to lock and load on them can be absorbing. Particularly when isolated from the mish mash of her peers. Yes indeed she is among the best and the brightest of the group of painters comprising "The Young and the Restless."

But this in depth look at the work at the MFA was an overload and circuit breaker. It was just more than the eye and senses can absorb. There is too much of a critical and curatorial apparatus here to throw it all up on the wall and just overwhelm and bludgeon the viewer with the work itself and the overreaching critical text that accompanies it in the catalogue with essays by Jeff Fleming, Linda Nochlin, and Linda Norden. Fleming who mostly provided the who, what, when, where and why includes a quote from an authority. In this case the designated scholar, Yve-Alain Bois, has sufficient gravitas. "Abstract painting was meant to bring forth the pure parousia of its own essence to tell the truth and thereby terminate its course." Bet you don't know what parousia means? Fleming's footnote states that parousia means "second coming."

Referring to the elements of the erotic in Brown's paintings, actually in this show far too tame with hardly a single blow job, this is, after all, the MFA, Nochlin, the doyenne with duende on matters of feminism and realism opines that "…the sex act serves as both an analogy and specific referent. Male artists have often made the explicit comparison between painting and fucking. Renoir, for instance, said that he painted with his prick. Brown has made it possible to speak of sex in relation to a woman artist- and it's about time." You go girl. So then, does Brown paint with her clit? Which entails, one assumes, a shorter brush stroke. Or does she use a strap on in the studio?

In Norden's essay she has a particularly rich and complex interpretation of Susannah which is a Biblical reference to Susannah and the Elders which represents a nude woman at her toilette being observed by the smarmy elders in a feminist trope of the male gaze. Dear me. But Norden deconstructs it cleverly as also a signifier of preparing for the male and the requisite approval of the elder or mentor. Norden probes into the personal, biographical and psychic meaning of the subject where mostly her essay involves the elements of touch, sensuality of surface, use of materials and mark making. In confessional mode having provided this complex analysis of Susannah Norden back tracks to exclaim "

What is always interesting about Norden's essays and communications are their gut wrenching honesty and passion. She can be narrow and didactic when discussing the few artists she champions but a careful reading of the Brown essay sets it quite apart from the bland praise of Fleming and the transparent, knee jerk, feminist agendas of Nochlin who really says little that is fresh and insightful about the work other than isn't it wonderful that a woman paints like this. Norden is always interesting and troubling in the manner in which she bobs and weaves, advances and retreats in an essay. We can feel the heat and fever of her mind like Jacob wresting with the angel. Her essay read carefully is filled with doubt and questions about the work which is actually dead on. She raises precisely the kind of tough and penetrating issues where the usual approach of catalogue assignments is "Let us now praise famous men (and the occasional woman)."

Yes there is much to praise as well as seriously doubt about this body of work by Brown. What's good and bad about it is its juicy materiality. The paint often is way too lush, loaded with oil and medium, producing glossy reflective surfaces particularly in the red, red, red and redder "Lady Luck" from 1999. The light reflecting off the surface is distracting. For an artist who has taken so much from deKooning's play book it seems odd that she did not realize that he often blotted the paintings with newspapers precisely to suck up the excess medium which resulted in matte textures that really allow the eye to absorb the surface and movements of the brush. In Brown's work there is too much frosting for us to taste the cake.

There is the stylistic anachronism to contend with. Just why would a contemporary artist like Brown be so literal in taking from the look and gestures of past generations and in particular deKooning? Yes, he was the greatest "painter" of his era (the greatest "artist" being Pollock). But their styles were so specific that they should be off limits. Does Brown get away with it just because deKooning is no longer with us and his last years were a shadow of his work in its prime? Has the statute of limitations lapsed long enough to just make straight up abstract expressionist paintings? In Nochlin's thesis since that was a macho movement the fact that a woman swings the loaded brush represents progress. But the serious question remains as to how far Brown has progressed from her sources: Titian, Velasquez, Goya, Freud and Bacon, the

The porn perhaps? Where deKooning had his snarling, nasty, misogynistic "Women" then Brown, as a woman, is taking back the night with copulation and quotes from the Kama Sutra. It is unclear why she feels compelled to slash and hack at the surface and drag her fractured brush about these big canvases. That is, after all, precisely what my generation learned in art school. And what we left behind and moved on from. Should we have just kept hacking? Is painting like bell bottom pants? If you keep them in the closet long enough do you get to wear them again? At least on Halloween. So, is Brown's work really just trick or treat?