Rose B. Simpson Legacies

Boston's Instutute of Contemporary Art

By: Charles Giuliano - Nov 03, 2022

ROSE B. SIMPSON: LEGACIES

At the Institute of Contemporary Art, 25 Harbor Shore Drive. Through Jan. 29. 617-478-3100, www.icaboston.org

Rose B. Simpson was born on the Santa Clara Pueblo in 1983. She matured in a culture noted for its distinctive pottery created by her mother, Roxanne Swentzell, her late grandmother, Rina Swentzell and her late great-grandmother, Rose Naranjo.

The doyenne of this tradition was Maria Montoya Martinez (1887, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico - July 20, 1980, San Ildefonso Pueblo). We first encountered her work and that of an immediate circle at the Denver Art Museum.

During a recent visit to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts we found her pots and other ceramic works prominently displayed in the recently reconfigured galleries of the American Wing. Significantly, the presentation makes no distinction between fine arts and decorative arts.

This is a signifier of progress regarding how Native American art and culture have evolved in museum and curatorial treatment. When the American Wing was first installed under former director, Malcolm Rogers, vitrines displaying vintage objects, craft and contemporary work were smashed together and literally the last work that one encountered when touring the installation. The sense was that of an afterthought.

Now we interact with several large paintings by Fritz Schoelder (1937-2005) and the museum recently purchased a major work by Jaune Quick to See Smith (born 1940) who is slated for a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

It is becoming ever more common to see work by artists of Simpson’s generation and emerging artists exhibited in mainstream museums. There was a transitional period when they were only displayed by museums that specialized in Native American culture like Denver Art Museum, the Heard Museum, Eiteljorg Museum, Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American in New York and D. C. and Peabody Essex Museum.

At the MFA, in its permanent collection, we found a graphic work by Simpson based on Maria. It’s an homage to Maria Martinez in which she modified and customized a 1985 Chevy El Camino with San Ildefonso blackware (glossy black on matte black) pottery designs.

Uniquely, Simpson is a multi-valent artist who works in ceramic, metal, performance art and has performed with a punk band. She is a trained and skilled auto mechanic in a culture for which the car has the traditional status of horses. The customized vehicles are both pragmatic as well as works of art.

Several months ago we viewed a mural-scaled photo of Maria as part of an installation of leaning ceramic figures at MASS MoCA. Her work was among the most interesting of a survey of developments in the field of contemporary ceramics.

It made one want to see more of her work. There is now a display of eleven figurative ceramic and metal pieces at the Institute of Contemporary Art. While we are grateful for that single gallery we regret that she wasn’t give more space. This was a missed opportunity to see works on paper as well as that iconic car.

What makes the work of Simpson and contemporary Native artists so compelling is the confluence of tradition- use of materials and subject matter – as well as the sophistication of contemporary approaches and techniques.

While emerging artists have the challenging of finding themselves, arguably, for the young Native artists that mandate is rooted in their heritage and DNA. It is a matter of giving it meaning, shape and form.

That process, in the case of Simpson, and for example Geoffrey Gibson, has been jump started by top notch education. Gibson holds a BFA from the Art Institute of Chicago and an MFA from London’s Royal College of Art.

Simpson studied art at the University of New Mexico and the Institute of American Indian Arts, Santa Fe, where she received her BFA in 2007. She went on to receive an MFA in Ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design in 2011 and another MFA in Creative Non-Fiction from the Institute of American Indian Arts in 2018. She is also a graduate of the now defunct automotive science program at Northern New Mexico College in Española, New Mexico.

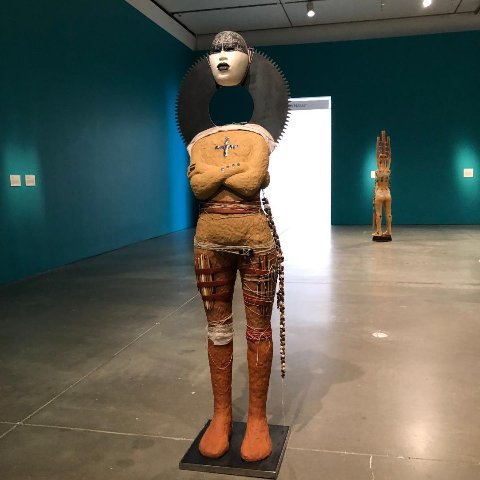

There is a totemic solemnity as we encounter Legacies at the ICA. Generally, they are standing, slightly under life-size, female figures. The construction derives from the ancient tradition of coil construction. She also creates forms with slab work.

The surfaces are rich with texture of the artist’s hand and presence. Mostly, the figures have the natural tones of redish/ brown fired clay. There are some markings but short of pictographic.

We engage the figures frontally at eye level and the impact feels direct, immediate and personal. Unlike much contemporary work there is no complex deconstruction entailed. The average viewer requires no special study or advanced degree to comprehend the artist’s intent.

A mother clutching a daughter fits nicely into the Madonna iconography of western culture.

Here and there some back story of required. Three adolescent figures form a triangle facing in. Their arms and hands are tethered. It’s a reference to the devastating impact of boarding schools which were created to deprogram children from their traditions and culture.

The brutal deculturalization in Canada is the subject of graphically visceral realistic paintings by First Nations artist Kent Monkman. Two mural scaled paintings were displayed in the lobby of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

We are grateful to the ICA for giving us such a compelling and personal exhibition. That’s all too rare when viewing installations of contemporary art.