Raymond Loewy: Designs for a Consumer Culture

Elegant Exhibit of Industrial Design Icon

By: Mark Favermann - Nov 03, 2007

At the National Heritage Museum

Lexington, MA

October 13, 2007 through March 23, 2008

Though just about as rare as four leaf clovers, every once and a while, there is a jewel of a museum exhibition dealing with an area of design. Several years ago, in fact in 1999, there was another one at this same institution on Frank Lloyd Wright and a less than well-known but extremely talented close collaborator, George Mann Niedecken.

The exhibit was titled Designing in the Wright Style. The show was superb both in quality of objects, historical context and presentation. Presently, the National Heritage Museum has another wonderful and high quality design show focused on the Industrial Design icon, Raymond Loewy.

A beautifully presented and layered exhibit, Raymond Loewy: Designs for a Consumer Culture, places his work in the wider context of the shaping of a modern look for 20th Century retail and consumer culture. The exhibit showcases his career and his life by a chronological selection of original drawings, models, products, advertisements, photographs, and even rather rare film footage of Loewy himself.

This designer's impact was so great that the show is like a cultural trip down 20th Century object memory lane. This is an exemplary exhibit that anyone interested in design or cultural history should see and savor.

Raymond Loewy was the Godfather of American Industrial Design. This comment is neither fanciful hyperbole nor just mild exaggeration. Loewy was to 20th Century industrial design as Frank Lloyd Wright was to 20th Century architecture. Just as Wright had his Prairie Style houses as signature work, Loewy was known for Streamlining.

Both individuals were consummate salesmen. And both got on the prestigious cover of Time Magazine at least once when this really meant something. Also, their names were identified by huge numbers of Americans for what they created.

This is more rare today. Perhaps, a few can name one or two prominent architects. How many people can actually name the most prominent industrial designer(s) in the 21st Century? Who can name the designer of the IPod? I don't think many can. Answer: he is an Englishman working for Apple named Jonathan Ive.

Both Wright and Loewy were amazing promoters of their own profession and craft. And certainly, each man was an even more amazing promoter of himself as the preeminent practitioner of his particular design discipline. Creative legends often need great self-promotion and creative gap filling. That said, this is not to take anything away from either of their spectacular professional accomplishments or skills. But, legends are often skillfully created not naturally developed.

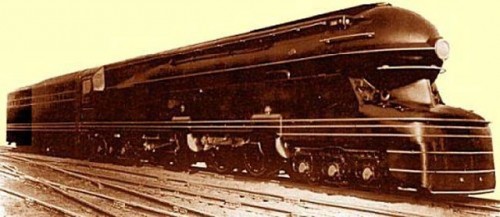

The range of Raymond Loewy's work was very broad, running the gamut from massive locomotives to personal lipsticks. Raymond Loewy and his various industrial design firms (and he had several during his long career) created some the most important design advances during the last century. Loewy spent more than five decades streamlining and modernizing silverware and pens, supermarkets and department stores.

Among other assignments, Loewy and his teams designed the color scheme and logo for Air Force One, the John F. Kennedy memorial stamp, place settings for Rosenthal China, the Greyhound Scenicruiser Bus, and the interiors for NASA's Skylab. Clients included corporate icons Nabisco, Coca-Cola, Exxon, Shell Oil and Lucky Strike cigarettes. Remember, like advertising agencies, design firms were not necessarily environmentally concerned or health-sensitive then.

Loewy was born in Paris in 1893. According to his biography, as a boy of 15, he designed a model airplane that won a major prize in 1908. Supposedly (this may be a piece of Loewy's own personal legend-making, like Wright's supposed childhood genius), he began selling them the following year. A captain in the French Army during WW I, he was wounded and received the Croix de Guerre. The legend continues as he supposedly arrived in the United States in 1919 with only his French officer's uniform on his back and just $40 in his pocket.

Living in New York, Loewy found work first as a window designer for department stores including Macy's. He also started to do work as a fashion illustrator for Vogue and Harper's Bazaar among others. This is an interesting point because several years ago, I met an older designer who had worked for Raymond Loewy in the later years of his practice. He told me that the firm's younger designers made fun of his sketch-making ability behind his back. This could mean that Loewy was the smooth suave salesman of illustration services who would sub-contract the actual illustration work to others. Or it could mean, as he got older, Loewy just got very sloppy in his drafting. i tend to believe the former.

In 1929 he received his first industrial design commission: he was asked to modernize the appearance of an early duplicating machine by Gestetner. Many other commissions soon followed, including work for Westinghouse, the Hupp Motor Company (interior styling), styling the Coldspot refrigerator for Sears and Roebuck and a long relationship with the Pennsylvania Railroad. From the start, he was highly entrepreneurial. Loewy opened a London office in the mid 1930s to take on UK and European clients.

Though others used it to modernize objects and make them look to be in motion while standing still, Loewy used streamlining as an attempt to design, shape and smooth transportation vehicles along aerodynamic lines for greater operating efficiency. However, it was almost always done for the sake of style and appearance. It soon became the dominant visual style of the 1930s. Loewy took strong ownership of the style through his bold work with locomotives. Eventually, he would become the best-known industrial designer in the world.

His firm's work moved to a redesign of the Coca-Cola bottle, creating and rebranding for Shell Oil and Exxon logos and Lucky Strike package. Styling and restyling interiors became a focus of the firm as well. The later years of his practice focused a lot on retail store design interiors and vehicle styling.

A great deal of design work was done by Loewy for the Studebaker Automotive Company as well. The designer was responsible for the sleek 1951 "bullet nose" Studebaker Champion. As shown in this exhibit, the Champion represents the first of the Studebaker line to have that particular style front end. The circular design in the interior instrument panel and dashboard was meant to convey the look and feel of an airplane cockpit.

The Studebaker connection lives on nearly 60 years later. The Avanti, a particularly stylized streamlined car created by Lowey, is still produced in limited custom production today and cherished by certain car aficionados.

This exhibit is a fascinating overview of the work, life and times of an American creative giant. This show draws on Loewy's personal archives, photographs and images not previously available to researchers in the past. Raymond Loewy died at 92 in 1986.

It has been said that he probably effected the daily life of more Americans than any other man of his times. This is an incredible legacy that should be shared by visiting this thoughtful and elegant exhibit.