William Christie Conducts at Lincoln Center

Handel's Theodora is Heavenly in White Light Festival

By: Susan Hall - Nov 01, 2015

Theodora

By Handel

Les Arts Florissants

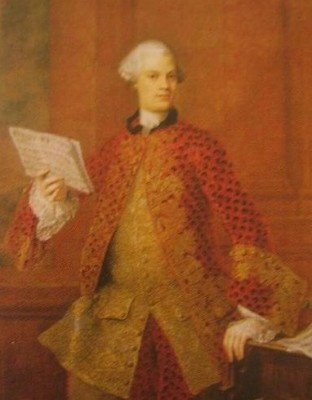

William Christie, conductor

White Light Festival

Lincoln Center

Alice Tully Hall

October 31, 2015

Katherine Watson, Theodora

Stéphanie d’Oustrac, Irene

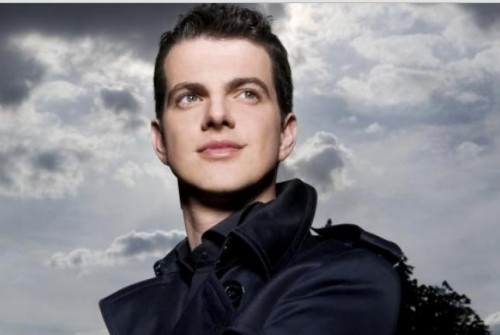

Philippe Jaroussky, Didymus

Kresimir Spicer, Septimius

Callum Thorpe, Valens

Theodora like so much of Handel’s music is transporting. Relaxing into the soft golden brown wooden frame of Alice Tully Hall, and listening to the perfection of William Christie and his Les Arts Florissants Orchestra would be more than enough for an evening’s pleasure.

The White Light Festival has brought an added dimension: language. Beyond the language of music are the words. English has never sounded more beautiful in song. Particularly the articulation of vowels helped voices ring out clarion clear.

Most of Handel’s oratorios were based on Biblical stories. Theodora comes from the 4th century and is a tale told by St. Ambrose. Plays and novels were soon written about Theodora, who chose death over prostitution. Handel’s librettist was Thomas Morell, a priest and classicist. For his adaptation he leaned heavily on a novella by Robert Boyle published in 1687 and reprinted in 1744. The Oratorio was first performed in 1750 and bombed at the box office. It has since become a favorite.

The governor of Antioch, sung with consummate command by Callum Thorpe, demands the sacrifice of a virgin in honor of the Roman emperor’s birthday. His henchman, Septimus, is reluctant. Kresimir Spicer as Septimus immediately pulls you into his orb. Not only is his conflicted role moving, but the voice is an unusual and satisfying mix of tones and textures. Even a short, guttural breath midphrase works.

Philippe Jarousssky, the Christian moral force of the piece, sings Didymus in a pure, elevating counter tenor. The head hardly seems to have a role in the production. Instead the voice emerges like a smooth stream of water, without a ripple or a twang.

Didymus admits to being a Christian and wants to figure out a way to save Theodora. All does not end well. Irene, Theodora’s aide de camp, warmed through the evening as mezzo soprano Stéphanie d’Oustrac engaged in her friend’s uplifting end.

The duets between Theodora and Didymus were exceptional. His voice is pure as crystal; hers full of texture and vibrato. Together they wound a gripping tone.

The form of staged stories has become popular as orchestras reach out to new audiences who are particularly attracted to music that weaves a tale. There is no direction credit for this staging, beyond the conductor's. Whoever is responsible did a wonderful job.

Singing actors used the walls to hide, chairs to mourn and contemplate, and twice a loud clap of shoe sole to floor called attention to a scene change.

The chorus was particularly notable. In one entrance half the chorus entered stage left and moved to the right. The other 12 members entered stage left and wove in front of the passing line to the right.

In another scene the chorus appears as disheveled party goers. For the finale they move stage front to detail the sad but, from a Christian point of view, triumphant end to the two main characters.

The pleasure that William Christie takes in conducting his musicians is conveyed in spades to the listener.

The only edge to the evening was the knowledge that the barbarism on stage was set in Syria, still a source of pain and confusion. The White Light Festival reminds us that music is not intended to remove us from the present, but to help us embrace the world as it is and give hope for what it might be.