Opera Boston's Beatrice et Benedict by Berlioz

A Scintillating Production Restores Faith

By: David Bonetti - Oct 28, 2011

Beatrice et Benedict

Music and text (after Shakespeare) by Hector Berlioz

Opera Boston

Cutler Majestic Theatre

Oct. 21,23, 25

Gil Rose - Music Director and Conductor

David Kneuss – Stage Director

Lesley Koenig – Producer

Robert Perdziola – Scenic and Costume Designer

Christopher Ostrom – Lighting Director

Cast:

Beatrice – Julie Boulianne

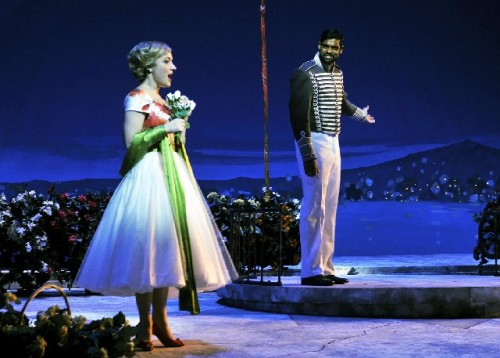

Benedict – Sean Panikkar

Hero – Heather Buck

Ursule – Kelley O’Connor

Don Pedro – Robert Honeysucker

Claudio – David McFerrin

Somarone – Andrew Funk

Leonato – Phil Thompson

The French have a word for it – charmant – and Berlioz’s Beatrice et Benedict and the production of it Opera Boston presented last week are charmant from beginning to end. It was the first fully successful production I’ve seen from Opera Boston since I took on the responsibility of covering opera in Boston last year, and it restores my hope that a local company mounting original productions can be more than provincial.

After saying that the opera and the production are charming, there’s really not a lot else to say, but being a critic, I will find a few additional things worth mentioning. And let’s not forget that true charm is a rare and fragile quantity, not easily dismissed, in art as well as in people.

Beatrice et Benedict, an opera-comique with spoken dialogue as well as sung arias, ensembles and choruses, was Berlioz’s last work, and you get the feeling that he was tired of the battles he had waged as a young man against the establishment to create a new, modern and identifiably French music. His final work, which premiered in 1862, is relaxed, more concerned with polishing apples than upsetting their carts. And it remains quintessentially French.

The opera is based on one of Shakespeare’s inconsequential comedies, Much Ado About Nothing, which Berlioz (1803-1869) made even more inconsequential by condensing, excising complicating sub-plots and focusing on the quarrelsome central couple of the title and a contrasting pair of “natural” lovers. Berlioz professed a love of Shakespeare – he had fallen madly in love with a tempestuous Irish actress who specialized in the Bard – but like most French adaptors, he didn’t trust him. Shakespeare is never neat and the French like their art balanced and rational. In cutting, he maybe cut too much. In Berlioz’s hands – he wrote his own libretto - the irrational hatred Beatrice and Benedict exhibit for each other is not believably demonstrated, and their last minute reconciliation and marriage come too abruptly and remain unconvincing.

In classic theory comedies always end in marriages, and Beatrice et Benedict ends with a double marriage. But this is not a marriage made in heaven – neither was Berlioz’s to Harriet Smithson. (She grew fat and alcoholic and they separated, although he continued to support her.) The two title characters have to be tricked into recognizing their love for each other and vow even as they exchange vows to hate each other later. The archetype is familiar: Katharine Hepburn specialized in Beatrice-like roles, sparring wittily with such Benedicts as Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant, Philadelphia Story probably the most enduring example.

But if Beatrice et Benedict is too slight to carry much dramatic or psychological weight, it remains compelling because of Berlioz’s glorious music. Even if the work is cynical about romance, Berlioz wrote shimmering, melting music for it. A master of orchestral color and dramatic contrast in tempi and dynamics, Berlioz showered his final work with rhapsodic music for orchestra, soloists and chorus. (His comic writing is less successful, and the buffoonish music master he created to replace other comic characters in the original, deflates like a lead balloon - although a chorus sung by local villagers in the style of an earlier century is amusing.)

The work abounds in glorious set pieces, none better than the duet between Beatrice’s cousin, Hero, the “true” lover, and her friend Ursule, who seems to have little else to do in the opera than to sing this rapturous duet with her, which ends the first act. Nuit paisible et sereine (calm and quiet night) is a nocturne of exceptional beauty that captures human emotional vulnerability and tenderness like few others. The two female voices, one high, one lower, mix in rare sympathy, creating a third voice. Supported by an orchestra rich in color, the voices mix with each other seemingly forever, making time stand still; in one magic moment, trilling together in a beat slowed to that of the human heart. There are few other moments like this in opera: Berlioz seems to have based this duet on one he wrote for Les Troyens, an epic opera that is arguably his masterpiece. Nuit d’ivresse et d’extase infinie (night of endless ecstasy), a prelude to a night of love by Dido and her faithless lover Aeneas, is one of the most meltingly romantic passages in the operatic literature. Both duets look back to Mozart, on whom Berlioz always kept an eye, whose weird little trio, Soave sia il vento, stops the action of Cosi fan tutte without warning.

Much of the success of the evening – I attended Tuesday night’s performance - was the result of the visuals. The Berlioz original, following Shakespeare, was set in Messina, Sicily during the Crusades. Opera Boston updated the action to Sicily in the 1950s, which gave set and costume designer Robert Perdziola the opportunity to create costumes based on the Italian neo-realist film of the era. The opening stage picture was breathtaking in its simplicity. A chorus of townspeople assembles to welcome the victorious troops back from battle (the updating didn’t always work – what war were Sicilian troops returning from in 1952?). Arrayed in casual ranks facing the audience, the women wear the full-skirted dresses of the period, all pastel colors and prints; the men wear the open shirts and sack jackets of the Italian peasant. Behind them the backdrop is more evocative of turn of the century Liberty Style (Italian art nouveau) than the 1950s, but who cares? It’s all so lovely, you’re immediately seduced into the Perdziola’s world.

In later scenes, Perdziola creates a terrace lined with flowering potted plants that overlooks the bay with Etna in the distance, all in tones of the blues of late afternoon and dusk. A ravishing set for the narcotic effects of Hero and Ursule’s duet.

After the fiasco of last season’s productions’ scenic elements – remember Fidelio and Maria Padilla? - Opera Boston should sign up Perdziola for as many future productions as possible. I missed his designs here for La Grand-Duchesse de Gerolstein, but I did see his contributions to David Carlson’s Anna Karenina and Mozart’s Il re pastore at the Opera Theater of St. Louis, and he brought a similar light but sensitive touch to both.

Of course, it’s all about the music. And the evening’s musical contributions were all deeply satisfying.

The muffled orchestral sound of the Cutler Majestic remains a problem, but once one adjusted one’s ear, music director Gil Rose found the right pulse for Berlioz’s ever-changing score. The opening might have been a bit crude – I thought of an orchestra in an Italian provincial house of the era the opera was set – but soon he settled into greater subtlety.

The cast was uniformly excellent. There’s no question that the rapid switch from sung to spoken passages is difficult for performers, especially when the dialogue is spoken in English and the music sung in French, as it was here.

(Which was, in my estimation, a wise decision. In opera comique works spoken passages are often taken over by a narrator, which kills whatever drama is occurring on stage. My only previous experience with Beatrice et Benedict was in Seiji Ozawa’s concert version with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in the late 1970s. Raul Julia served as the narrator, and one wanted to shoot him - he was such a ham, the singers had no defense. I experienced a similar problem last year when James Levine conducted Bartok’s Duke Bluebeard’s Castle in the same hall. Frank Langella was so in love with his own voice that he didn’t prepare for the evening – he read the text as if he were experiencing it for the first time. I could go on – the performance of Fidelio with the St. Louis Symphony Orchestra with Christine Brewer that I left at intermission because the narrator was so annoying, etc.)

Most of the singers managed to get by as both speakers and singers, although they fortunately excelled in the latter capacity. Local veteran Robert Honeysucker, who sang the small part of Don Pedro, a general of the victorious Sicilian forces (that mystery war again), proved most adept at his spoken responsibilities. Despite his long and successful career as a singer, one realized he could have been an equally good stage actor.

As Beatrice, mezzo-soprano Julie Boulianne was a fiery dissenter in the game of sexual politics. Short, blond and dressed in a full-skirted floral dress, she darted around the stage, reminding me of Giulietta Masina, the memorable comedienne of Federico Fellini’s films (and his wife). Her richly toned mezzo was a perfect fit with the role. Her extended “conversion” aria, Il m’en souvient, in which she realizes that her hatred for Benedict is really love, was beautifully sung, her character visibly and audibly melting from obstinacy to acceptance. And Boulianne, a Canadienne, was exemplary in her French enunciation. (I hope the other singers were listening.)

As Benedict, tenor Sean Panikkar nearly stole the show, even if his solos were not in the same category as the female cast. Tall, handsome and virile, he was swoon-worthy when he emerged in the last scene in his military uniform, tight white trousers and a military jacket that made his shoulders look as if he were wearing a Joan Crawford costume. His richly textured voice was even in all registers, rising to high notes effortlessly. I’ve heard Panikkar in St. Louis as Lensky in Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin and Count Almaviva in John Corigliano’s Ghosts of Versailles, and he was equally impressive in such diverse repertory. He’s a singer to watch and to look forward to.

In a pale yellow dress, Heather Buck as Hero was totally glam. (Did they have such chic women in Messina in the ‘50s?) In the opening scene, I thought she was Beatrice, since visually she so seemed “leading lady.” But even if she played second fiddle to her cousin Beatrice, she got to sing the opera’s great number, the duet that closes the first act. Before that she had her own aria, which she effectively put over, although her voice wavered insecurely as she ascended the scale. In “nuit plaisible et sereine,” she and Ursule, mezzo-soprano Kelley O’Connor, seemed held back from fully embracing the orgasmic nature of the duet. It was lovely, the highlight of the evening, and both singers were totally committed to their art, but it was understated when ideally it should have been more assertive.

In other roles, David McFerrin as Hero’s betrothed was a cipher, which was all his undeveloped role required. David Thompson as Leonato, the governor of Messina, a spoken role, was majestic in his white suit. Andrew Funk as the buffoonish Somarone, which translates as “big ass,” didn’t seem up to the comic demands of the thankless role.

But, as I said at the start, it was all quite charmant. I wish I could see it again.