Art History and Anti-Art

A Clark/Getty Public Conversation

By: Jane Hudson - Oct 24, 2006

Sitting around the café at the Clark Art Institute, in the afternoon of October 21, members of the audience sipped wine and chatted in knots while the 'fellows', visiting scholars from the Getty Fellowship program and current (and future) Clark scholars, as well as a few guest artists and curators, waited to address the subject of 'anti-art' as an art-historical category as well as a phenomenon of modern culture.

Michael Holly, director of the Clark Fellows program, introduced the speakers and framed the evening's remarks as a wrap up of a weekend-long colloquium wherein the participants explored the issue of anti-art and its historical precedent, iconoclasm.

Charles Harrison, Getty scholar and Conceptual Art specialist, identified the three periods of history, we might call them moments of 'novelty', that changed the nature of art and its marketplace.

1. The Reformation in England when religious icons were eschewed and the merchant class emerged.

2. The French Revolution, the destruction of privileged images and the expansion of the middleclass.

3. The 1960's where non-objective practices (video, performance, installation, conceptualism) were introduced into the art discourse, and a new market was defined.

In addition it was suggested that 16th Century destruction of religious images in the Netherlands broke the connections to patronage and created a new system of portable, disposable objects.

Heinrich Dilly, Clark Fellow and a student of the works of Walter Benjamin, especially "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction" in which he critiqued the traditional, sacred object and its 'aura' of authenticity as against the new 'object of exposition' (in particular film, and by association all technologically produced images) wherein the intrinsic is sacrificed for the sake of a dialectical agency.

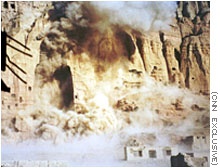

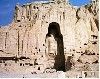

Ancient acts of violence such as the destruction of images of Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut and the pharoh Akhnaten during periods of historical revisionism can be compared to acts against the figures of Buddha destroyed in the Taliban's fundamentalist backlash in Afghanistan. This begs the question of the positive or negative consequences of such acts. Clearly the cultural and political frame of reference directs the affect.

Barbara Bloom , an artist and Getty scholar, discussed the Japanese practice of repairing broken objects with gold, thus celebrating the 'crack' in the form as a moment of contemplation. This is such a Zen contradiction of the Western notion of wholeness and perfection.

Ernst Van Alphen, a Clark scholar from the Netherlands, suggested that Modernism itself can be characterized as anti-art in that since the earliest gestures of Dada and Futurism, art is seen as transformative and productive, breaking with institutions rather than destructive of images. (this also reminds of the Benjamin notion of the 'expositional object').

Guest mathematician Wertheim suggested that the history of science is fraught with critiques of scientific vision (e.g., the non-linear evolution of the Earth) from fundamentalists wherein new forms evolve from the destruction of older models.

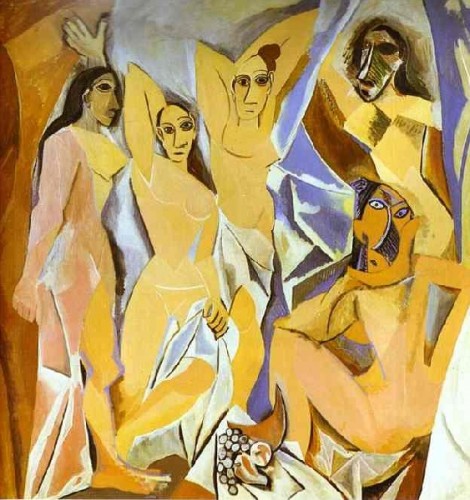

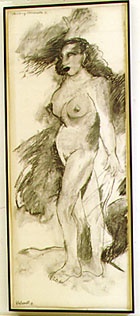

Lowery Sims, the founder and former director of the Studio Museum of Harlem, Metropolitan Museum of Art Trustee, and Clark fellow (Spring session) remarked on the strategy of artists of color to appropriate images from art history wherein the 'exotic other' has been employed into the Western canon (e.g., Picasso's ' Les Demoiselles D'Avignon' revisioned as Robert Colescott's 'Demoiselles D'Alabama') in order to shift the power balance.

After these instructive introductory theses, the audience was invited to continue the conversation. Rauschenberg, for example, erased a deKooning drawing, which was given to him by the artist, in an act of permitted critical subtraction. He erased the 'value' of the work, but brings the critique of value to bear on the wider discourse of the art market. (It was noted that it made a difference only because deKooning was highly valued already as was Rauschenberg, so there was an even exchange and a developmental value).

Finally, the crux of the matter was opened up when it was suggested that Art History itself is iconoclastic. By offering interpretation, the critic distances the viewer from the direct experience of the work. As well, the specific interpretation may be exclusive of other readings, and thereby limit the experience of the work. It was argued, however, that the art historian should not be too penitent, as the function to elucidate the work opens up the experience of the work to many people who would otherwise be unable to make any sense of it.

(Editors note: In the famous incident where Rauschenberg "erased" a drawing that he requested from deKooning it should be noted that Rauschenberg took as much time and labor, arguably even more so, in the careful and deliberate process of removing the marks of the other artist. The irony, of course, is that such a Dada gesture has entered the canon of the avant-garde in such a manner that, today, the resultant "blank" sheet of paper is more "valuable" because of its unique nature and significance as an "action" than an intact deKooning drawing from this period. Ultimately it is now "more interesting" in its current state than the "lost" original. But one should not assume that deKooning was pleased at the fate of the drawing that he gave to a younger and then less famous artist. C.G.)