Class Distinctions at the MFA

Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 22, 2015

Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Curated by Ronni Baer

Through January 18, 2016

There are 75 works in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston exhibition Class Distinctions: Dutch Painting in the Age of Rembrandt and Vermeer curated by Ronni Baer.

Of the marquee artists there are two paintings by Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) and four by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669).

Vermeer died relatively young and was not prolific. During his life he was modestly successful and left little in the way of inheritance for his heirs. The works are greatly prized and arguably each of the 34 known paintings may be viewed as masterpieces.

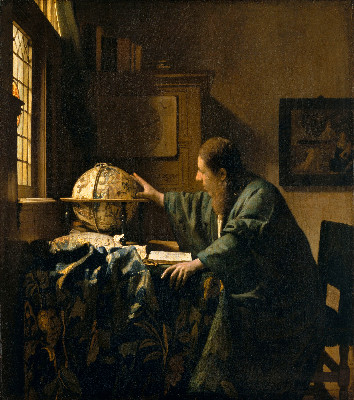

The two Vermeer paintings in this exhibition- “A Lady Writing” (National Gallery of Art, Washington) and “The Astronomer” (Musee de Louvre, Paris) are quite different in mood and tone but both are ravishing.

There was a third Vermeer in Boston but “The Concert” was stolen from the Gardner Museum, a short walk from the MFA, some years ago.

Of the four paintings by Rembrandt on view two “Maria Bockenolle” and “Reverend Johannes Elison” are large companion portraits in the collection of the MFA. The other two are “Jan Rijcksen and His Wife, Griet Jans” A.K.A. “The Shipbuilder and His Wife” (British Royal Collection) and “Andries de Graeff” (Museumslandschaft Hessen Kassel, Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister).

Considering that Rembrandt was more prolific his works on view at the MFA shrivel by comparison to the selection of Vermeers. It is a stretch to argue that they are masterpieces although the term surfaces for “The Shipbuilder” in the museum’s PR which notes that it is the first time that the canvas is being seen in an American museum.

Having chosen the theme of examining class what’s on view at the MFA is a selection of good but not great works from the Golden Age of 17th century Dutch art. Most of the foremost artists are included but not with their iconic works.

Notable exceptions are the astonishing “Courtyard of a House in Delft” (National Gallery, London) by Pieter De Hooch which is always a pleasure to view as well as the intriguing and beautifully painted “Interior with Women beside a Linen Cupboard.” The artist is particularly masterful in the treatment of natural light in the "Courtyard." It is almost abstract in its stark formality. By comparison there is a mood of domesticity as a maiden assists the woman in folding and putting away the family linen.

During the 17th century the Dutch prospered through international trade. Its Eighty Years’ War with Spain (1568-1648) finally ended. Dutch traders and slavers introduced tobacco and sugar to European markets.

In this time of expansion, colonization and exploitation it was possible for the lower and middle classes to acquire great wealth. It resulted in the creation of a bourgeois society eager to acquire art as a means of social status. Artists like Rembrandt and Frans Hals were commissioned to paint portraits of merchants, and members of civic and military organizations.

The style and subject matter of Dutch art was different from the classical tradition of Roman Catholic Italy and Spain. There the primary patrons were the church and aristocracy.

Because the Dutch were protestants, other than the private pursuits of Rembrandt, there was no iconoclastic religious art.

The primarily nouveau riche, vulgarian collectors, cluttered their walls with relatively new categories of subject matter. The genre scenes they embraced and readily understood were inspired by the Flemish master Pieter Breugel (1525 - September 1569). A common theme of this work focuses on the folly and antics of drunken and randy peasants.

Other accessible themes for bourgeois collectors were landscape and still life paintings. Often they conveyed ideas of the sumptuous life enjoyed by patrons as well as moral signifiers of the Seven Deadly Sins.

Lacking the intellectual basis of classicism this Northern European style was more Dionysian- derived from Grunewald, Bosch and Breugel- than Apollonian.

There was actually an Italianate style in the Candlelight Painters of Utrecht who were inspired by Caravaggio. There is work by one of these artists, Gerrit Van Honthorst, but he is represented by an atypical portrait “Amalia van Solms.” It has none of the dramatic lighting that the artist is best known for.

If the selling point of this generally enervating selection of secondary works was the drawing power of Rembrandt and Vermeer it is curious that the curator did not include any work by Judith Leyster. The revisionist text books replacing those of Janson and Gardner now give Leyster equal billing with Rembrandt, Vermeer and Hals. But, significantly, not at the MFA.

There are so many artists in this exhibition who should have been represented by better works. One might start with Frans Hals who is represented by three works. Perhaps the best of the three is one of the group portraits for which he was best known “Regents of the St. Elisabeth Hospital in Haarlem” (Frans Hals Museum).

Compare and contrast the Hals standing portrait of “Willem van Heythuysen” which is hung next to a similar portrait by Rembrandt “Andries de Graeff.” With sumptuous detail of signifiers of social status from costume to gilded sword Hals has delivered on the demand for a grand and flattering portrait. It has none of the insight of character and quirkiness of the casual pose and glove thrown to the floor in the Rembrandt portrait. We learn that the patron refused to pay and this was a tipping point in the decline from fashion and wealth to poverty that marked the life of Rembrandt.

Today Rembrandt’s massive (actually cut down) canvas “The Military Company of Captain Franz Banning Cocq” A.K.A. “The Night Watch” is widely viewed as among the artist’s greatest works. It was, however, a failure at the time. The patrons of the company who paid equal shares to be represented were not depicted as such. Similar Hals paintings and those of other portrait artists take no such liberties to “composition.” In the center of “The Night Watch” is an image of the artist’s wife Saskia with a dead chicken dangling from her waist.

Rembrandt violated the first rule of portrait painting which is to flatter the patron. This is also why the rather conventional MFA portraits of the Elisons have always struck me as a bit of a bore. In this exhibition they hold their own in generally mediocre company.

There are four works by the master of genre painting Jan Steen. He is a very great master who is not represented by his best works. Steen presents a mid brow approach to genre. He mostly depicted the middle class and wealthy at decadent play. Compared to which Adriaen Brouwer, one of my favorite of the Dutch Masters, wallows in the comical gutters of lowlife. His paintings of smokers and barfing drunks are hilariously wonderful. I assume that most visitors to the MFA will hardly notice his small and moody “Interior of an Inn.”

The MFA has assembled an enjoyable overview of Dutch art which will surely entice and amuse its audience.

For me, of course, the sublime take away was an opportunity yet again to devour the two exquisite Vermeers. With just two examples we experience the range and brilliance of the artist.

There is a soft glow to the colors of “A Lady Writing.” She looks out at us in a pool of light against a subdued background. The costume, a yellow satin jacket with ermine trim, suggests wealth and leisure. Her hair is tied up with ribbons. Does this suggest a casual, at home demeanor and we are entering her private space as trusted visitors? Is she perhaps a prostitute as is the case in other works by Vermeer including “The Concert?”

The interior space of “The Astronomer” is more strongly illuminated. The artist intends us to see and study the iconography of objects in the composition. The man reaching out to touch and turn the globe is a scholar. He is emblematic of the advances of science and technology of the era. This included the development of lenses for telescopes, eyeglasses and artists’ devices such as the camera obscura which it has been argued Vermeer may have used.

Having taken in the exhibition we returned to the Vermeers to spend more time absorbing their radiance. The experience was truly inspiring.