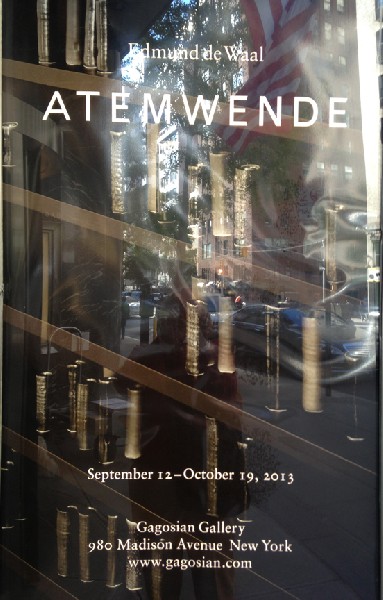

Edmund de Waal Ceramics At Gagosian Gallery

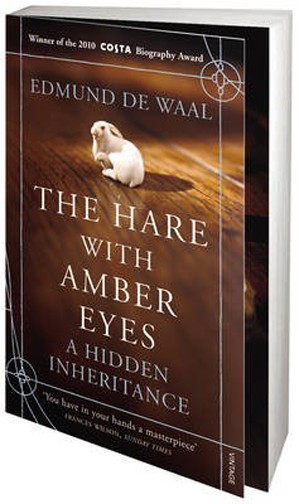

Porcelain Pots Panoply By Author of the Hare With Amber Eyes

By: George Abbott White - Oct 21, 2013

A confession: I “read” text and images, but less frequently objects. My last experience with ceramics was a very poor pot I threw in high school, though I came to know Steuben glass about that time through a first girlfriend’s engineer father.

Pottery is pretty old stuff. Legions of archeologists have re-constructed the pre-Homeric world from large and small shards of crockery and crude and elegant drawings on jars I’ve seen. Pottery is craft, a complex mix of ideational design and its physical execution on wheels, “throwing” and then glazing, temperamental kilns and their mysterious temperature swings, and an amalgam of material, equipment, knowledge, experience, and luck.

More than one knowing critic has commented on the distinguished British ceramicist Edmund de Waal’s extraordinary transition from craft to art. In Hare With the Amber Eyes (2010), de Waal’s recent international best seller and richly textured memoir of his Central European Jewish Ephrussi family’s odyssey—from 19th century Odessa rags to late 19th century Paris and Vienna banking riches to Holocaust evisceration, the “potter” refers frequently to the sheer and subtle kinesthetic knowledge and kinesthetic pleasure of things. The Ephurussi bankers were second only to the Rothschilds in wealth.

Their shapes, textures, weight and mass, de Waal asserts, remind us every waking hour, however conscious or unconscious we are in their presence, of their influence and power. Which is to say that the busy closing of de Waal’s NYC Gagosian Gallery exhibition October 19th was for this untutored spectator less a show or exhibition than an installation of interlocking, multidimensional puzzles over which the Hare memoir hovers.

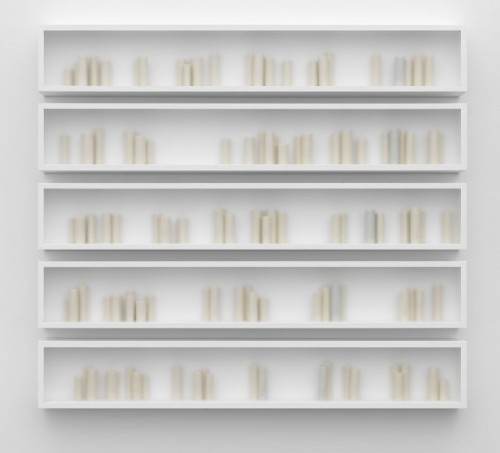

Less a display of utilitarian or artistic ceramic objects, meant to be seen and touched, than an invitation to complex and contradictory intellectual speculation put into play by almost two and a half thousand pieces, in two large rooms, on two floors, more than two dozen cases, 16 shelves high at some points, eye level at others. Speculation, about what?

First puzzle, the basic set up or playing field. Just how many containers or “cabinets” is the viewer asked to engage? The two “maps” Gagosian Gallery provides in a handout list eleven cases or vitrines on the 6th floor, eight on the fifth. They are all very plain, undecorated, toplit from multiple small, ceiling spots. OK, nineteen total? But three actually are formally subdivided, not one but three sections. So nineteen plus an additional six, for twenty-five, and another case, 5th/#7, is in fact two separate black aluminum “girders” on end. So twenty-six? Not quite.

Two more cases are internally subdivided into three(6th/#7) for twenty-eight. OK? Whether the handout is correct or counting another way than the careful viewer only begins the questions, and deepening of one’s uncertainty, since the meaning of the experience of these objects must in some way be conditioned by the context and presentation the experience. Therefore, everything appears ambiguous and puzzling.

Another tension introduced by the set-up is that the vitrines’ size ranges enormously. From a single shadow box-like case 22 1/16th inches square (yes, we’re down to 16ths) to a unit almost floor-to-ceiling 90 7/16th inches x 118 1/8th inches within the same room. The viewer is constantly scaling from one extreme to another.

Edmund deWaal no longer handles humble clay it seems but strictly porcelain, and there is plenty of it. The 2474 pieces, plus several plates which might be considered backing, do not look like the graceful, boldly glazed cups I was given twenty years ago by my late Kyoto friend, Ken Akiyama—who praised the work of a unknown young potter—nor the softly luminous pictures I’ve seen of de Waal’s previous gracefully minimalist work.

These are almost all small, each between 2 ½ inches – 4 inches high and about 3 inches in diameter, the many narrow ones, almost tubular, diameters maybe an inch or less. Unornamented, all are without handles, and many exhibit exterior surfaces that are often irregular deckled, rippled, pock-marked, serrated, scored; some lips with flaps,others almost grotesque (as in the large cabinets on the 5th floor).

Glaze varies along a minimalist pallet, creamy bone white or chalky pearl, dark browns and deep blacks; a few with what seems flecks of gold or narrow gold rings around the lips or bases. What one sees is less attractive or pleasant, in a conventional sense, than interesting. And one’s puzzled interest is guided in what feels increasingly as a kind of consumerist tent show by de Waal’s intent;an intent scattered in clues on the two floors and extrapolated from that other, very determining text, his Hare With the Amber Eyes.

For deWaal’s a smart guy, well read, knowing about art, artists and poets, and the contrary and often conflicted way art works. He invites, he occasions a “close reading” and like billiards rather than pin ball, moves you by slight touches. So the arts and literature are foreground, not background.

Edmund de Waal’s favorite Ephrussi family forbearer, mid-19th century Charles, constantly referenced in the memoir, not only was a friend of Proust’s but said to be the model of Baron de Charlus in Swann’s Way. This Gagosian Gallery show takes its title, “Breathturn,” from a 1967 poetry collection by that violent anti-Semite Paul Celan (another puzzle, given a family vandalized by the Nazis) but alludes to Wallace Stevens, as the memoir also rings the changes on Titian and Vermeer, Rilke and Isaac Babel, Dreyfus and Eichmann.

With a sensibility as informed and inclusive as de Waal’s, there is something contradictory behind all this contextual body English in the placement of pieces. As one moves here and there to view, several thousand “vessels” are not immobile in their containers.

About these works de Waal states he was, in part, exploring “silences,” how so? Certainly apparent in how pieces are placed, in seemingly casual configuration. Why 302 vessels in 6th #3? Why not 301 or 303? A lone piece on this shelf here, on its right three in a group, five a few inches away, then two still farther right. Why did de Waal place them thus?

The bulk of the pieces, particularly those in the multiple-shelved large cases, remind this viewer of sawed-off garden hose, thick hose; small interior diameters and thick walls. Was de Waal after an “industrial strength” look? How does that bulk mesh or conflict with earlier notions of craft?

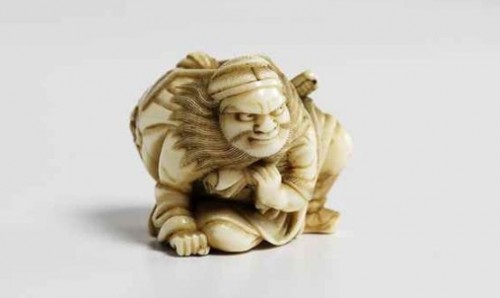

Edmund de Waal answers the question in Hare With the Amber Eyes. Tomokazu, the early 19th century Japanese carver whose life and work de Waal admiringly describes as “gifted” was a craftsman “who excelled in making netsuke animal figures.” He put time not just skill into his work, “It was not rare,” de Waal writes, "that a month or two months were spent in making a single figure.” Single? But then netsuke must be different than pots.

Even though one can get close to the cases, there is no touching, like de Waal’s Great Uncle Iggie did fondling the netsuke in Vienna or Tokyo or de Waal’s three children placing and repositioning them in the old/new vitrine in London. It is often unclear just what you are seeing.

Most of the cases are open, that is, unenclosed. But aside from the complicated groupings and distracting (Is this intentionally so?) vessel surfaces, edges and dark uninviting glazes, one of the two large cases on the 6th floor actually has a frosted plexiglass front and pieces in several cases (6th/6 and 6th/10) appear “ghostly” in their indistinctness, because the case backing is false with the vessels only dimly seen through the dark and translucent backing.

Another spectator assured me that I was mistaken as the back was a true back, images of the pieces had actually been painted to give the ghostly appearance. Hmmm. Two guards I asked disagreed, they said that there were vessels behind a false, translucent backing. I go with the guards.

Far along researching The Hare With the Amber Eyes, de Waal says he nevertheless “stumbled to a halt.” His initial curiosity upon receiving the 264 netsuke figure after Iggie’s death at 84, the small intricate Japanese wood and ivory carvings created decades, even hundreds of years earlier, had consumed years of de Waal’s life in archives and interviews across Europe, written and phone exchanges from his father in the south of England to Paris, Vienna and Odessa.

Ultimately, it led de Waal away from his workshop and back into a colorful and troubled past he had hardly known, the great weight of European history, the collision of empires, fortunes, wars, cultures, racial hatreds and fascist brutalities as well as the interplay of national and personal suffering and tragedy that he could hardly comprehend.

In exasperation de Waal wrote, “I no longer know if this book is about my family, or memory, or myself, or is still a book about small Japanese things.” Some 350 pages into it, any fair-minded reader must conclude, now it’s about all…and much more.

If books could speak, and speak with one another (which they often do) walking around the bland Gagosian Gallery floors, Daniel Mendelsohn’s epic search for what happened to his family during the Holocaust, Finding the Lost, might begin the conversation. And Martin Gilbert’s harrowing travel narrative from one Central European “crime scene” to another, Holocaust Journey, adding not merely horrific details but an historic frame.

Having lost virtually all their vast banking fortune and grand residences, their winter and summer “retreats,” each collecting immensely valuable “stuff” (de Waal’s characterization), de Waal’s immediate, not all by any means, family were fortunate to finally let go of that “stuff,” barely escaping the Nazi cattle cars and death camps, though with little more than the clothes they were wearing.

Growing up modestly, in a rented house in Kent, UK, de Waal nevertheless attended Cambridge though Anglican priests like his Dutch father do not amass much wealth. And his grandmother Elizabeth’s postwar attempts at “restitution,” Austrian-style, were reflexively, cleverly, callously and humiliatingly deflected. Still, de Waal was encouraged to find his own way, making pots if that was his heart’s true desire. A concluding contradiction.

Humble beginnings, particularly those engineered by men rather than the gods, are a not an uncommon spur to imagination, certainly not with writers and artists. The greater the loss, the greater the spur?

A recent Artnet post remarked that early on de Waal made “inexpensive pots” on the Welsh borders. More recently, however, the Financial Times named de Waal as not only “one of our leading contemporary potters” but, it’s the Financial Times after all, “highly collectable,” with each of his vessels fetching “between 2500 and 50,000 pounds.” Low balling the Gagosian Gallery show at $2000 USD a piece and taking with a barrel of salt an overhead conversation between two gallerists that “it’s gone very well, most of it’s sold,” that’s a cool $4 or $5 million. Even with the gallery's 50% commission, that's still pretty good.

Some of the Gagosian Gallery viewers might recall that Hare With the Amber Eyes is subtitled, A Hidden Inheritance. Play on words, another contradiction perhaps? More than once in his memoir de Waal criticizes the Ephrussi family’s overly ostentatious “extravagance” that also, or simultaneously we might argue, patronized the art of a Renoir or a Degas, financially supported the cause of a Captain Dreyfus, and blew some fresh wind into the sails of a Rilke.

Visiting Vienna’s imposing Palais Ephrussi on the Ringstrasse, tastefully restored and now world headquarters for Casinos Austria, an eager young staffer gives de Waal a tour in the course of which de Waal discovers that the servants’ quarters in this enormous five storey pile occupied a hidden floor-between-floors. It was reached only by a hidden staircase and which space was, regrettably, windowless and airless.

Except for the faithless Ephrussi doorman “who leaves the gates unlocked” for post-Anschluss Gestapo entry, the other servants (including the faithful Anna who rescues and then returns the collection of netsuke) remain nameless, aptly echoing Brecht’s excoriating poem, “A Worker Reads History.”

De Waal's Great Uncle Iggie, who left the Palais before the 1938 occupation of the mythical “first victim,” Austria, luckily made his way to New York City, then California, before a WW2 U.S. This was followed by an Army stint through Normandy to Germany as translator and intelligence officer allowed him to re-invent himself as a slowly successful grain importer in General MacArthur’s postwar Japan.

Bringing the rescued netsuke collection, Iggie begins a decades-long relationship with a young and aesthetically resourceful Japanese companion, Jiro Sugiyama. Tokyo like Vienna, Paris, Odessa and England rebuilds. Iggie and Jiro live well, travel and, as de Waal notes, prosper, a hundred years “after his grandfather opened the bank in Vienna." The family always felt that Iggie was not cutout to be a banker. Yet, somehow, Uncle Iggie became the representative of Swiss Bank in Tokyo. He was, de Waal ironically notes, “an Ephrussi after all.”

Of course, great nephew Edmund inherited the netskes and the narrative as well as the pottery seemed to flow from them.

With so many variables playing with the viewer and the interventions of the craftsman/artist, a little like Pascal’s characterization of God, everywhere present but no where obvious, it might be reasonable to consider this latest presentation of de Waal’s “self” a parody and, also, a critique on the state of his art and the context of its reception, valuing and commodification.

His ceramic pieces have non-utilitarian shapes and their uneven seemingly unfinished lips, small bits of material here and there. Their uninviting glazes save for a few lustrous bone white and very pale green and dark purple finishes were addressed by one reviewer as “naïve.” If by “naïve” one means “childish” that is certainly one possibility though the more Romantic reading of “child-like,” simple, stripped, without artifact might be more to the de Waal’s point.

One suspects fewer pots, and another book, as there is much more story, not only in Paris, Vienna, Tokyo and Odessa, but in the family origins in the City of Berdichev as well for this potter who has discovered that he, too, is ‘an Ephrussi after all.’

Yet puzzles still abound. After 70 some years, wouldn't it be nice, no fitting, to have a last name for the loyal “Anna” who set this all in motion?