Daniel Kershaw Stages the Show

The Art of Native America at the Met

By: Jessica Robinson - Oct 20, 2020

“The Art of Native America” at the Metropolitan Museum

Before covid and shut-downs, millions of viewers each year passed through the galleries at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art looking at Daniel Kershaw's stagings. He is a design star you’ve never heard of.

As Senior Exhibition Designer at the largest museum in the United States, Kershaw’s job is to plan and build environments for up to a dozen shows annually.

While most museum installations are designed to spotlight the art, not steal the show, there are times when being awed by the installation itself is the whole idea.

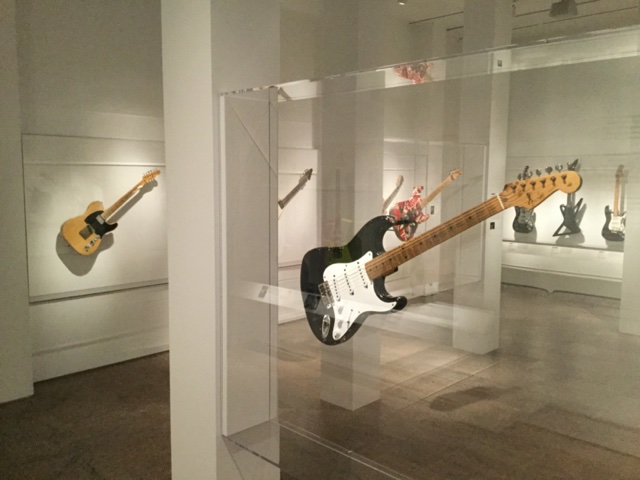

“I expected bad behavior,” says Kershaw, referring to the eye-popping exhibition, Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock and Roll, a pre-covid (April- October 2019) block-buster show that celebrated rock music’s history through the1960s –‘70s.

On display were the tools of the rock trade - guitars, drums, keyboards, amplifiers - from Jerry Lee Lewis’s gold baby grand piano to Bruce Springsteen’s Fender Esquire guitar and John Lennon’s 12-string Rickenbacker. These were the very instruments used by the rock gods to change music – forever.

“Much of my design for Play it Loud was centered on letting people get right up to the instruments to see the sweat stains, cigarette burns, and worn spots,” explains Kershaw. But who would have imagined an adoring fan would plant a juicy red lipstick kiss smack dab ON the plexiglass display of Keith Richard’s hand-painted guitar?

Of course very few exhibitions are ‘loud.’ Some are very quiet, as evidenced in the current show, Art of Native America, a definite contrast with Play It Loud.

Art of Native America, (from the pioneering collectors Charles and Valerie Diker,) is an elegant, simple-looking installation that is intentionally peaceful, even when the artwork is a musical instrument, or represents an act of violence. There is no music, either, for fear it would “easily slip into stereotypical concepts, and be annoying to the slow visitors and the guards,” Kershaw says.

Even the text is subtle, “it's too easy to put too much design into a show. Text may sometimes stick in peoples' minds, but I hope the visual impact of the art is what makes the lasting impression.”

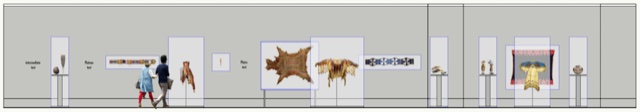

The galleries for this exhibition cover the entirety of North American native cultures over a vast timeframe. Much of the art is light sensitive and needs to be rotated off view and exchanged for other works, requiring a very flexible open flow of spaces.

The exhibit is made up of over one hundred of the best examples of Native American masterworks including bowls, baskets, pottery, textiles, masks, figurines, drawings and paintings.

It can’t be easy to shape such a vast personal collection that represents a variety of diverse cultures over so many years. Each bowl, basket, and moccasin had to be adjusted to the best angle and orientation to meet the eye as one enters through the principal approaches. “It was necessary to give each object space, as if they were individual people, with a variety of personalities,” explains Kershaw. “Some get along well while others need to be separated.”

Consideration was given to the power of individual artworks, their relationships, the stories they tell and their functions.

Take the series of woodlands bags with beautiful shoulder straps too delicate to support them. Kershaw decided that rather than flatten them against a wall, he would mount them in order to make them freestanding. The effect is that “ they greet you in the first gallery space, floating but carefully supported with the curved straps appearing as if hanging from shoulders, seeming to bear the weight of the bags.”

Another example is an elegantly painted hide, too fragile to show vertically, which Kershaw and his team mounted with rare earth magnets. And, there’s the beautifully decorated parka made by a Native Alaskan woman using dried seal-skin intestines and adorned with puffin crests. It was originally so flexible it could be squished into a small ball and stuffed into a kayak, but now needed careful easing and padding into a form resembling a human body.

The job of exhibition designers is complex and collaborative. They are responsible for each exhibition from beginning to end. But how does a project begin?

“I start by meeting, many times, with the museum curator to first understand the story he/she wishes to tell. I am by nature a very collaborate designer. I work with lots of people of varying degrees of expertise: conservators, mount-makers, engineers, carpenters, machinists, graphic and lighting designers. I consider myself more of a generalist, and rely on these colleagues to come up with the best possible design.”

“Then I take the objects, images, and information he or she provides and assemble them in a way that protects the objects while communicating the story to museum visitors in a visual way that hopefully makes a lasting impression.”

To do his job, Kershaw uses computers, drawing utensils, paper, and other equipment, but the real tools are light and shadow, color, form, shape, texture, sound, smell,(mummies for instance,) memory, and space. These are the basics of communication in an exhibit.

And how does it feel to have such a special one-on-one intimacy with so many incredible objects? “It makes me feel very much alive in my job.

From a very young age I was fascinated with design. There's something of that same kid-like rapture that this job evokes as you're dealing with the most important and extraordinary objects from our culture and history,” expounds Kershaw, happily.

After thirty-two years at the Met he is still feeling the rapture.

To view the show click here:

https://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2018/art-of-native-america-diker-collection

This exhibition is on-going.