Morgan Bulkeley Retrospective at Berkshire Museum

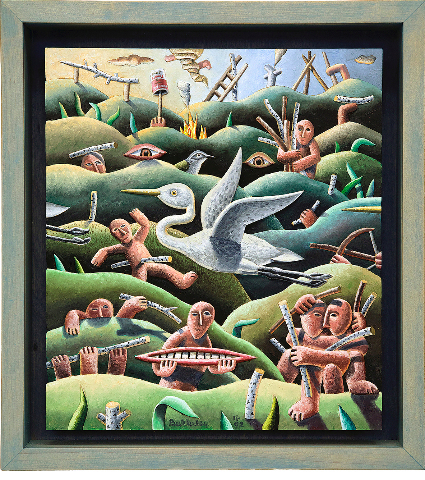

Last of the Mohicans

By: Charles Giuliano - Oct 08, 2017

Morgan Bulkeley: Nature Culture Clash

Berkshire Museum

September 29 to February 4, 2018

Catalogue, 94 pages, illustrated, published by the Berkshire Museum

Essays by Geoffrey Young and Eleanor Heartney

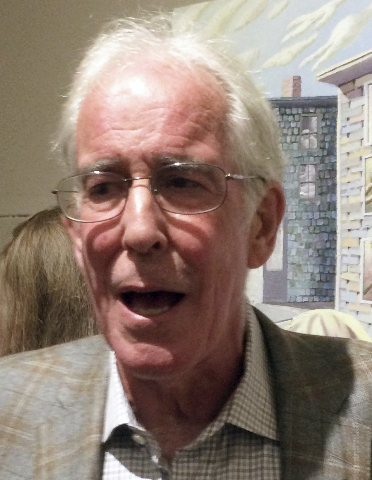

It was thrilling, poignant and terribly sad last night when many artists, friends and community packed the Berkshire Museum for a vernissage of the sprawling, eclectic, and dazzling retrospective Morgan Bulkeley: Nature Culture Clash.

The artist, who was born and raised in the Berkshire hamlet of Mt. Washington, was mobbed by friends and well wishers. There are regional deep roots in his DNA including fundamentalist preachers, patriots, politicans, a poet/ farmer father and gardener/ naturalist mother.

He grew up playing in the woods pretending to be an Indian. His parents rescued and nursed back to health birds and animals. These sources filtered into the work as an autodidact after earning an undergraduate degree in literature from Yale University in 1966. An avid reader he evolved as a narrative artist with rich and diverse sources of material.

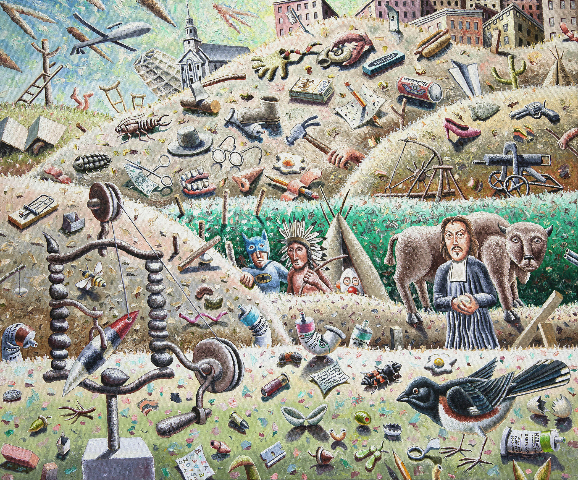

Looking at the staggering array of dense and wacky works, with their plethora of eclectic details and daunting iconography, there seems such a natural fit to the endangered heart and soul of the museum itself. There was an easy elision from viewing his paintings to wandering off to immerse in the wunderkammern of objects in the galleries. There is a mish mash culture clash of plaster casts, Palmyra sculptures, taxidermy, Asian curios, animal and bird skeletons, 18th century moccasins, ephemera and gonzo stuff.

Just like Morgan’s enticing and evocative paintings.

At least last night, perhaps for the last time, the Berkshire Museum was just that in every sense. It was a setting to gather, celebrate and respect the work of a native born and deeply rooted artist. In the Crane Room we noted a work by Bulkeley from the permanent collection.

What will become of it and other works by notable, Berkshire connected contemporary artists in the collection, once vulgarian Van Shields and the board dump 40 key works to jump start their New Vision? They refuse to discuss plans with the media so nobody can report with authority how the fine art and a collection of 40,000 objects will be conserved and displayed in the future.

Approaching the artist, who I have known and covered for decades, I asked how he felt about being The Last of the Mohicans? In his charming and whimsical manner he rather liked the image given his deep interest in Native American Culture. It is a subtext in many of his works. There are hogans in his paintings precisely like one on view in the galleries. Arguably, the artist grew up with that dwelling which then emerged, as did so much of the ephemera, in the mature works.

It is a vivid and compelling testament to the deep influences the museum has had in the development of kids growing up with visits to the evocative exhibitions.

A couple of times when I checked back with him Morgan asked “Did you see Miro?”

By that I assumed he meant our mutual friend Miraslav Antic. I looked for but didn’t find him. Morgan clarified, it was an early portrait in the first gallery, an antechamber of juvenilia as one enters the exhibition.

Eventually, I found it and was deeply moved to discover that in every sense, it was indeed, the heart and soul of Miroslav gazing out at me. (It is reproduced on page 7 of the catalogue but the colors of pages, 6, 7, 30 and 31 are way off. The rest of the reproductions, however, are superb.)

With a commonality of narrative imagery and representation, the Boston School which Morgan and Miroslav were essential to, was a backwater against the isms on their generation. Stemming from Boston Expressionism, on a national level, given pervasive careerism of mainstream artists, curators, critics and collectors the Bostonian love of figuration was brushed off as provincial and reactionary.

The reputations of the best artists never seemed to get past Route 128. There were, to be sure, supportive local galleries and collectors. After a few shows, however, it was ever more challenging to sell new work. Some artists like Miroslav and Paul Shapiro left town and found new markets in Florida or Santa Fe.

Last night it was great to catch up with Morgan’s pals, Anne Neely, David Phillips and Mark Cooper. Others in their circle include Gerry Bergstein, and Taylor Davis. These artists are included in the catalogue essay by Geoffrey Young. I would add to that the artists Henry Schawartz and Domingo Barreres, influential teachers at the Museum School, as well as Robert Ferrandini, early Doug Anderson, Jon Imber, Todd and Judy McKee. There is a sidebar of polemical artists Arnold Trachtman and Dana Chander, Jr. One sees in Bulkeley elements that have appeared in Bergstein’s paintings. He relates the impact of viewing the figurative works of Philip Guston.

Becoming reacquainted with “Cambridge Street” 1972, “Moon in Day” 1974, and the series of three-decker apartment houses from 1976 through the mid 1980s, reminded me of when we were all young, sanguine, hungry and primitive.

There is a crude, raw energy to this outsider phase as was surely my early effort to write about those artists. It would be nice to say that, as with Morgan’s ever more complex and sophisticated works, we have gotten better with time. By now, hopefully, we know better and there are more and sharper arrows in our quiver of metaphors.

It is always revelatory and harsh to look back at our early work. In some ways I wince at viewing those early paintings just as much as reading old reviews. An artist neighbor was clearing out and sent me a copy he saved of an early review. We laughed about it with him pointing out the error that he did not use airbrush. Overall, we agreed, it was not bad, considering.

Looking at those tenement paintings was an acorn thing. It was the seed from which grew the mighty oaks creating a later thicket of creativity cramming the galleries.

It is a show that one would like to see number of times were it not for trepidation of crossing picket lines. I spent a couple of Saturdays standing out with other protestors.

Like Hitchcock’s “Rear Window” the artist engages us in voyeurism. We are peeping toms gawking at folks making love or in the nude. There is the fun of recognizing art world and literary celebrities. These snippets and references would explode and become every richer and more complex as the work evolved becoming more focused and skilled,.

Morgan’s work would be a great topic for a graduate seminar or thesis. There are lots of art-about-art references and gleanings from news, history and popular culture. That guy with the wild, blond, comb over is a recent vignette.

One could approach the work as a visual essay on the turbulence, history and environmental impact of our generation. No subject appears to have escaped his witty and anecdotal grasp.

At some point he expanded from the brush to carving polychromed reliefs of birds as well as biomorphic, free standing sculptures. There is a wall of large carved masks and opposite to it one with several colorful, twisty walking sticks. Imagine taking a hike in the woods with one of them.

If the artist has looked outward for his iconography there is also a turning inward. Memories and losses of his personal life have found expression in the oeuvre.

There is a haunting “Portrait of My Father” 1996. The accompanying critical text reveals that he was blind for his last 25 years. On an earlier occasion, during a group show at Ferrin Gallery, we discussed his own vision issues. Here we find a large head with glasses askew. There are four birds partly obscuring his face. A hand clutches pencils, the tools of a poet. The mouth is open with a splay of bad teeth signifying the grimace of suffering.

In a recent interview the artist told of many losses of family, friends and loved ones in the past couple of years. It is a generational issue we share and identify with. The artist has the advantage of flipping the personal into universal.

I left this deeply moving evening with a harrowing sense of sharing the turbulent voyage of life, spelled out in his work. It is an adventure from which no traveler returns. But let us speak of it while we can. Particularly when, with Morgan’s work, it is eloquent and poetic.

Call me Ishmael.

By the way, come to think of it, Melville was a Berkshire artist.