Laurie Anderson's Habeas Corpus

Project with Mohammed El Gharani in New York

By: Susan Hall - Oct 05, 2015

Habeas Corpus

Laurie Anderson and Mohammed El Gharani

Park Avenue Armory

New York, New York

October 2-4, 2015

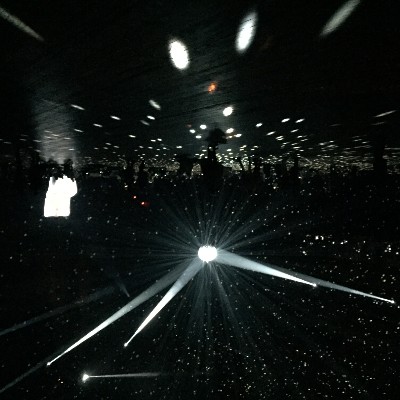

Entering the drill hall at the Park Avenue Armory in New York, the cavernous hall is transformed into celestial space.

I do not know what the sky looks like to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, but I have spent time on Culebra Island off Puerto Rico and these areas have about the same latitude and longitude. I sleep on a deck when I am in Culebra so that I can be embraced by the canopy of stars that hover above and around me. The plains of Texas have some of the same feel: infinite, perfectly beautiful, quiet. All seems well in the world.

By contrast, what we definitively know has gone on at Guantanamo is the inverse of the night sky. It is ugly and inhuman. We have taken our response to the red scare of the early 1950s and raised it by the 16th power.

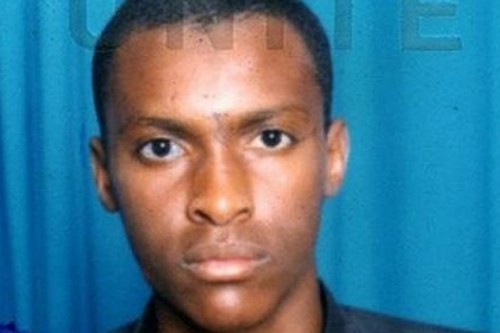

El Gharani was arrested in a mosque in Pakistan and taken to a jail cell where he was hung by his wrists. Electrodes were attached to his feet for 10 days. He could not walk. He was tortured because he knew nothing about Osama bin Laden.

Transported to Cuba, he was told his jailers had thrown away the key to his cell. He was there for life.

An organization called Reprieve was able to get him released in 2009. He is not a live part of Habeas Corpus because he can never come to the United States.

Anderson is a co-collaborator with El Gharani, a soft-spoken gentle young man who is now struggling to put his life back together in West Africa.

Anthropologist Margaret Mead argued that if you portray one member of a group in painfully intimate detail, you can understand the group. Habeas Corpus does this with one boy/man.

In one small room at the entrance of the Armory, El Gharani tells his story on video from start to finish. It is easily transferable to any device or theatre and should be widely seen by US citizens.

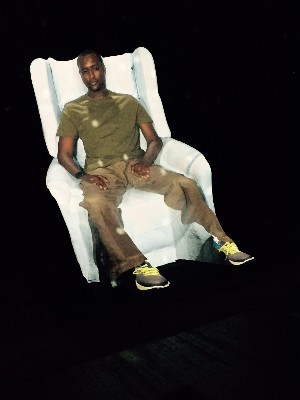

Anderson has cast herself like a Ben Shan miniature in another room. El Gharani is at the scale of Abraham Lincoln’s statue at the west end of the National Mall in West Potomac Park. Anderson is tiny.

Anderson was in New York for 9/1l. Like all of us who saw the crashing planes live, the day is etched forever in memory. It hovers over us. Anderson writes: "They could come from the air."

Being present at this installation is like being at the New Museum’s show of art that came out of the Bell Labs. Music fills Anderson’s hall. It is sometimes eerily Middle Eastern, and at other times harsh and cacophonous.

People are lying all over the floor, very quiet, absorbed in thought. They are also propped up on walls and on benches. Standing in front of the projected El Gharani invites a selfie.

I stayed for two hours and could have remained longer. Maybe we do need a permanent Gitmo exhibit in Washington. We have no trouble pointing fingers at the atrocities of others, but perhaps we need a strong, permanent selfie of ourselves at Gitmo.