Akikazu Iwamoto at NY's Stux Gallery

Eye Candy

By: Yelin Qiu - Oct 05, 2013

Imagine this show as candy for the eye and, for those who quiver at the sight of the surrealist distortion of bodies, queasiness in the stomach. Hiroshima-born Akikazu Iwamoto, now forty, fills his compact solo show at Stux Gallery with wildly imaginative, candy-colored paintings and drawings that involve amusing and sometimes frightening bodily transformations. The result was a surprisingly confronting, and often wicked, commentary on our inflated inner desires.

One small painting, The Hero, features a young girl in superwoman cape, a pair of goggles on her head, a tiny swaddled baby hung on her nose, and an enormous bomb and a stack of weight plates dragging her downward. The hope of life brought by the baby and the impending death announced by the bomb seem to joyfully coexist.

The artist, who was raised just two miles away from the Hiroshima bomb site, must have seen images of human suffering since childhood. The devastating yearning for life in the post-Hiroshima world would seep into his art, as hybrid animals and distorted human bodies gleefully go about their business. This yearning, or a sort of manic joy, is perhaps less present in his recent paintings than in his earlier ones.

His earlier drawings featured more animals, and color combinations were brighter and less sinister. In his recent paintings, which greatly resemble his drawings in their beige paper-like background and in the crosshatching-like brushstroke. The spontaneity and experimental energy of his earlier drawings lingers, however, the subject has grown distressingly dark and confrontational.

Drawing from traditional East Asian paintings’ use of endlessly expansive negative space, Iwamoto’s works are built upon an empty and seemingly limitless field of beige-color. Such pictures imply an abstracted space, perhaps even a psychological landscape. The artist cites Maurice Utrillo and Giorgio Morandi as influences. To the extent that the artists invite the viewer to a certain mood and certain psychological state, Iwamoto adheres to these European masters. His body of works, however, are quite a departure from Utrillo and Morandi’s simple composition and muted subtlety of tones, in their style, and decidedly richer than the former masters in their overtly psychoanalytic demeanor.

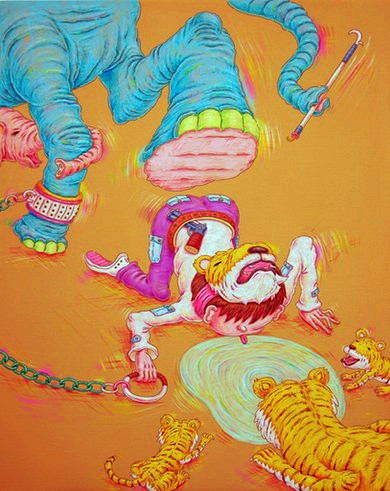

Here you may find themes of medical exams, animal cruelty, violence and pain. Bodies are maimed, distorted, covered, and swollen. The narrative is as enticing as it is repugnant, and viewers’ reaction to these pictures is immediate and visceral despite the lightness of the palette. A particularly striking picture, The Water 2, depicts a girl in a tiger mask, kneeling in a dog-like position licking water from a puddle. A tigress and two cubs are drinking from the same puddle. She has one end of a leash on her hand; the other links to the enormous elephant, which is sneaking up and about to crush her with its foot.

In Iwamoto’s world, the cross-identifications between different consciousnesses and the vulnerability of the human being causes much unease in the viewer.

The French psychoanalyst, Jacques Lacan, theorizes that infants initially experience their bodies in fragments, and gain their first illusion of wholeness of the human form when they encounter a mirror. The shattered bodies in Iwamoto’s pictures hence interrupt the illusions of wholeness in our imagination, pushing back at us as if we stumbling infants looking into broken mirrors.

The show is titled after the centerpiece, portrait of a girl, with one hand raised to her lips signally “hush”, the other taking her mask off, revealing a distorted face grappling with a candy. The “Secret Candy” might not be so secretive after all. It’s all tangibly shown on the bodies. Our bodies.

By Yelin Qiu reposted from NYArts Magazine.