Uzbekistan: Part Two

Shakhrisabz and Bukhara

By: Zeren Earls - Sep 30, 2013

Our journey south began at 7am. Driving through streets decked with banners saying “Mustaquillik Bayraminiz Mubarak Olsun” (“Happy Independence Day”), we left Samarkand amidst the euphoria of the approaching 22nd anniversary of breaking off from the Soviet Union. We passed by vineyards flanked by the foothills of the Pamir-Altai Mountains, known for their grapes with 30% sugar content, a primary source of raisin production. The foothills undulated like giant sand dunes, their shadows alternating with sunny patches. Goat herds grazed near villages of single-story mud-brick houses. The other side of the road was a totally flat, arid plateau with an occasional rider on horseback. Patches of green appeared near water channelled in concrete troughs through fields.

As we entered the Kashkadarya region, the outside temperature was 40°C. We turned off onto an unpaved road flanked by wheat fields, to reach a village where rugs were made using natural wool. Our host family — father, mother, two daughters, and grandmother — greeted us warmly, offering green tea, non bread, and raisins. Beautiful kilims (flat-weave carpets) in all shades of natural wool hung on racks. I purchased a small kilim, patterned in rows of light and dark brown.

Cotton is a major crop in southern Uzbekistan, which is the third-largest producer in the world after the US and Egypt. University students are part of the labor force hand-picking cotton. By building a dam, Tajikistan has blocked the water supply to the Amu Darya River, which originates in the Pamir Mountains. In an area that can reach 50°C in the shade, scarcity of water is a problem. In addition, since the area is in an earthquake zone, all of Central Asia would be flooded should the dam break. The Uzbeks have referred their dispute with Tajikistan to the United Nations.

Our lunch stop was in Shakhrisabz (“Green City”), named after its many gardens. It is also Tamerlane’s home town, originally known as Kesh. Although the jewel of his empire was Samarkand, Tamerlane took great care to strengthen and beautify Kesh.The town preserves a rich store of history in its architecture and has a leisurely atmosphere with its chaikhana (teahouses) and traditional homes with gardens; we enjoyed lunch in one of these.

The ruined entrance arch and towers of Ak Serai (“White Palace”), whose name symbolizes Tamerlane’s noble descent, stood as a monumental testimony to the ruler’s power. Unparalled in size and decoration when built, the towers require a stretch of the imagination from their current height of 38 meters to their former height of 65 meters, although the base of the arch is still dazzling. Nearby, Tamerlane’s colossal statue attracted many visitors, including newlyweds. A Kufic inscription on the east flank of the palace reads “The sultan is the shadow of Allah.”

The centerpiece of the Dorut Tilovat madrassah is the Kok Gumbaz (“Blue Mosque”), named after its blue dome and built by Tamerlane’s grandson Ulug Beg in 1435. The mosaic tiling on the portal and 10-meter arch was restored in 1994. The madrassah’s porticos flank two surviving mausoleums — that of Sheikh Shamseddin Kulyal and the Gumbaz Sayyidon. The former houses the remains of a Sufic leader and spiritual advisor to Tamerlane’s father; the latter holds four tombstones of the sheikh’s kinsmen.

The Dorus Shadad nearby is a family mausoleum which Tamerlane built for his sons Jahangir (“World Conqueror”) and Umar Sheikh, and includes a crypt for himself, which later received two anonymous bodies. Attached to the Dorus Shadad in the 16th century, the Hazret i Imam Mosque, with an iwan or covered pillared portico, faces a courtyard shaded by chinor trees.

After a taste of sweet melon offered by roadside vendors, we were back on the road heading south. We drove through the Karshi steppes, a national park area for wildlife such as deer, moose, jackal, falcon, and eagle. Turning west, we continued through the steppes, occasionally spotting domesticated camels, and arrived in Bukhara at 6:30 pm, ending our almost 12-hour journey.

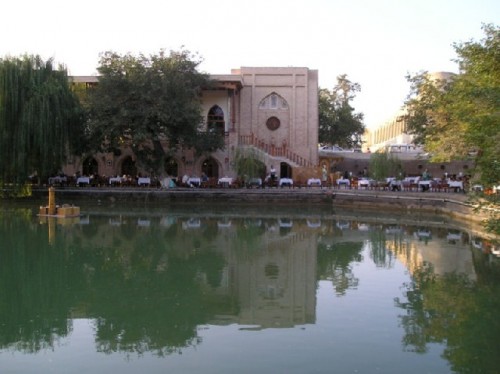

The Hotel Siyavush on a quiet back street was our home for the next three nights. A modern two- story building, the hotel is named after the founder of Bukhara, a Persian prince, who built a citadel here in the 6th century BC. Following dinner and a birthday toast to Joseph in our group, we strolled through the narrow lanes to the center of the old city, Lyab-i Hauz Square, Bukhara’s famous landmark and a Unesco World Heritage site. The square buzzed with people, who go out after sunset as a relief from daytime heat.

The following morning our tour started on foot – the only way to negotiate the streets of the old city with its historic structures, many of which have been restored as museums and craft workshops. Walking through the bazaars, we visited the Carpet Museum in the 12th-century Magok-i Attari Mosque, which has a fine selection of Turkmen and Tekke carpets. Next was the Museum of the Blacksmith’s Art, run by a family of blacksmiths who have plied their ancient trade on this site for generations. A fireplace in the shape of a water jug reached the dome of the transformed 16th-century Bozor-i Kord Mosque, matching the brickwork of its interior. Steel knives of all sizes and shapes with bone handles lined the walls, while a row of brass samovars and trays graced a high shelf. Down the street, sparks flew in the Iron Masters’ Workshop as one craftsman shaped a knife while another etched a copper plate.

A visit to see the Bukhara Silk Carpets was equally alluring, as shoeless men kept furling dazzling carpets before us. Sabina, the owner, explained their unique qualities. Some were double carpets, revealing a different design on each side; others combined pieces with different colors of the same design as two halves of one carpet. A tree with pomegranates, symbolizing fertility, was the central motif of yet another unique carpet.

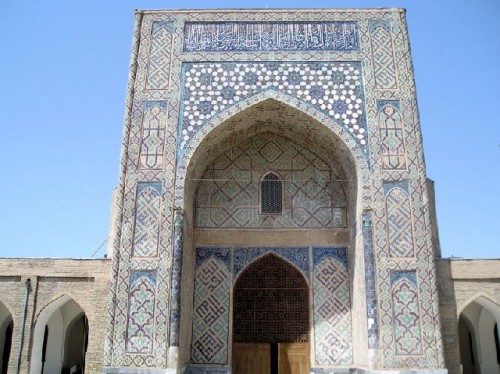

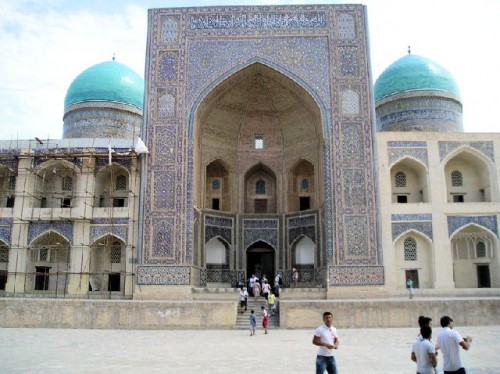

Outside in the shade of the historic buildings, salesmen spread their wares, such as fur hats and Uzbek dolls. We continued on to the Poi Kalon, or “Pedestal of the Great,” the square that is the religious heart of Holy Bukhara and separates the Mir-i Arab madrassah from the Kalon Joma (“Friday”) mosque. Towering over the city at over 48 meters high, the Kalon Minaret tapers from an octagonal base through ten individual bands of honey-colored geometric brick designs up to a 16-windowed rotunda gallery. Dating back to 1127, the minaret has suffered natural and man-made disasters over time and is now under UNESCO protection.

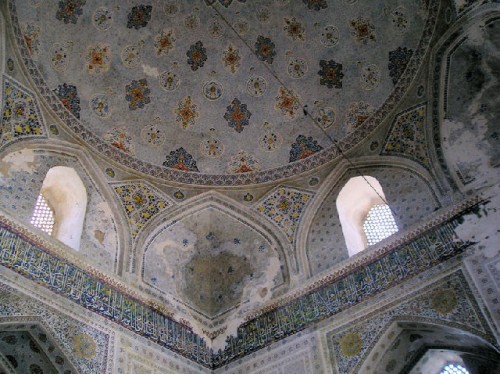

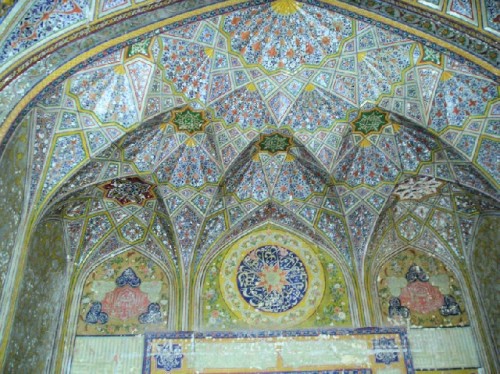

The Kalon (“Great”) Mosque is the cathedral mosque of Bukhara, built simultaneously with the minaret to house the entire male population of the city during its weekly main namaz prayer. The present structure retains the rectangular plan with a huge central open-air plaza encased in an arcade of 208 pillars and 288 domes rising from the roof. The main entrance is through a beautiful portal facing the square. Although the mosque’s doors have reopened to embrace Islam, its congregation fills only a tiny corner of its deep cloister.

Active Mir-i Arab (“Prince of the Arabs”) madrassah, named after Sheik Abdullah of Yemen, faces the Kalon Mosque. It is one of the most esteemed Islamic universities in post-Soviet territory. Resident students take a four-year course of studies in Arabic, theology, and the Koran, as the first step to becoming fully fledged imams. Constructed in the 16th century, the madrassah has the traditional layout of two floors with student cells. The alabaster grills of the cells enhance the attractive facade, with its fortress-like buttresses and twin jade-colored domes.

The Ark Fortress facing Registan Square is Bukhara’s medieval citadel; it began to take its present form in the 16th-century under the Uzbek Shaybanids. In the last three centuries, in addition to housing the emir and family, it grew into a complex of over 3000 inhabitants providing a palace, harem, throne room, reception hall, office block, treasury, mosque, gold mint, dungeon, and slave quarters. From the stone ramp entrance, a narrow winding arcade climbs alongside the row of cells and torture chambers into the heart of the Ark. The surrounding rooms of the courtyard provide exhibits, revealing local history, including the final robe worn during the emir’s coronation ceremony.

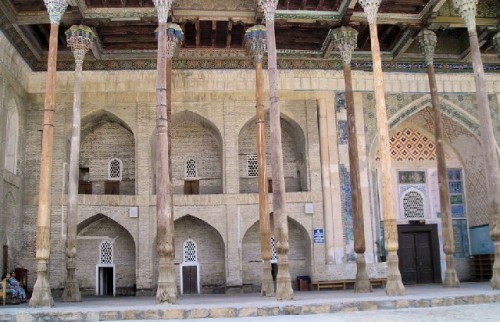

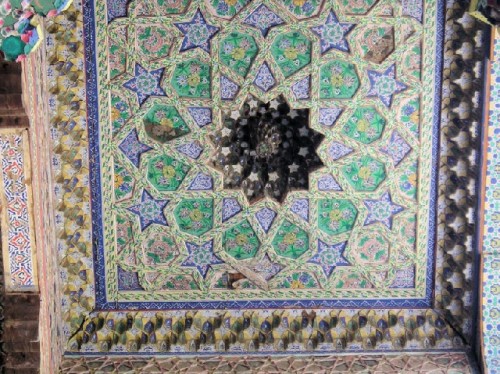

Bolo Hauz is the royal court mosque. Every Friday the emir would walk on a deep red Bukhara rug spread for him from the Ark to the “Mosque near the Pool.” Today the 18th-century mosque is still active, after a brief Soviet interlude when it served as a worker’s club. The mosque has 12 meter-high wooden pillars, each made by joining two trunks; they have carved and painted stalactite capitals. The mosque also has ornate wood ceilings.

Following a busy morning, lunch was at an outdoor restaurant, where locals share a meal on wooden beds with cushions around the food, which is eaten by hand. Although we enjoyed a kebap lunch at a regular table, I was allowed to photograph a group of local men. Back on the road, a five-minute walk due west of Registan is the Ismael Samani Mausoleum, the family tomb of the founder of the Samanid Dynasty (875-999). The 1000-year-old cube-shaped mausoleum, with its identical facades and crowned by a dome, is majestic in its simplicity. Basket-woven brickwork set in a series of complex patterns shifts emphasis with the angle of the sun. The corner buttresses and thick walls are woven in weightless delicacy. Also rich in symbolism, the cube refers to the sacred Kaaba stone in Mecca, as well as symbolizing the earth as a complement to the dome, a symbol of the heavens, thus creating a metaphor for the universe.

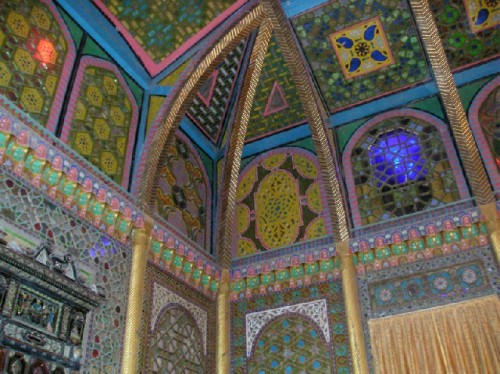

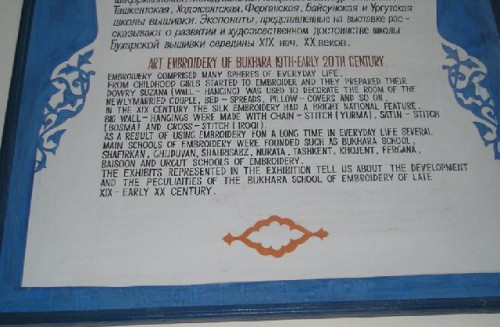

Sitorai Makhi Khosa is the Emir’s country residence, also known as the Summer Palace. Built by the Russians in 1911 for the last Emir, Alim Khan, it is a mixture of Russian and Central Asian architecture. Past the colorful grand entrance arch is an outer courtyard leading to the reception halls of the inner courtyard, with a lime-green alabaster iwan along one side. The palace complex includes the European-style main building, the harem quarters in the garden, and the pool. Today the harem building is a Museum of 19th and 20th-Century Ethnography and Embroidery.

During free time in the afternoon, I went to see the puppets of Iskandar Khakimov, a master puppeteer with an extensive collection. Located in the Lyab-i Hauz complex, his workshop displays puppets in national costume representing folk and literary characters. The attractive features of an Uzbek puppet in traditional ikat silk dress compelled me to buy it.

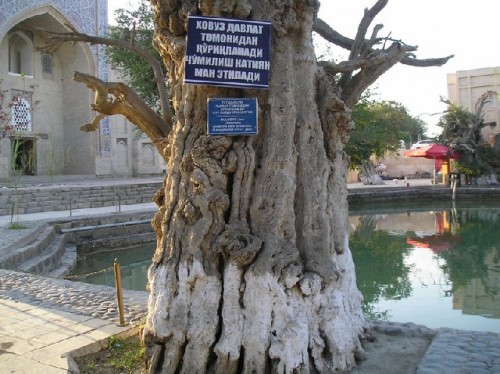

A walk around the Lyab-i Hauz revealed the soul of a land in transition. The surrounding historical buildings, reflected in the waters of the old city reservoir, and mulberry trees dating from 1477 lined the banks of the stone steps. Locals mingled with tourists at chaikhanas; women with bank accounts in the form of gold teeth sold souvenirs; a statue of Nasreddin Khodja, the legendary wise fool of Central Asia and Anatolia, sat on his donkey enticing children. Locals admired modern brides in white wedding gowns, posing with their grooms for photographers.

Dinner was in the inner courtyard of the Khanaka madrassah, dating from the 1630s, the first in the Hauz ensemble. The courtyard hosts a nightly concert and show by the fashion boutique Ovatciya, which occupies one of the cells, overflowing with handicrafts. The clothes presented included traditional fabrics — silk, khan-atlas, and cotton — and evening gowns with gold embroidery.

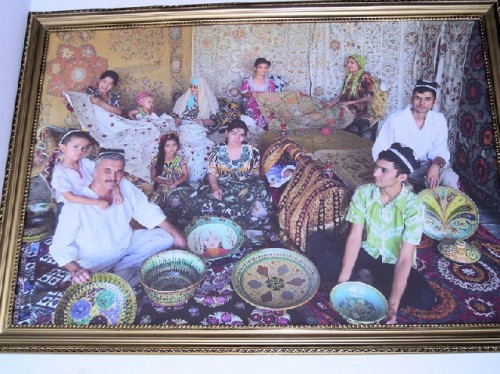

Our final day in Bukhara started with a trip to Gijduvan, to visit the pottery workshop of Abdulla Nasrullaev, the seventh-generation primary ceramic center in the country. Children shaped clay near a family portrait of the potters with their wives and embroidery. We were treated to green tea, cookies, raisins, and nuts. After watching a potter at the wheel, we learned about the process. Quality clay is attained locally by removing the top soil. Objects shaped on the wheel are painted with floral patterns and geometrical designs, which distinguish the Gijduvan style, onto a white, red, or yellow foundation before firing. Admiring the variety of ceramics displayed on walls, niches, and tables, most of us walked away with several treasured objects.

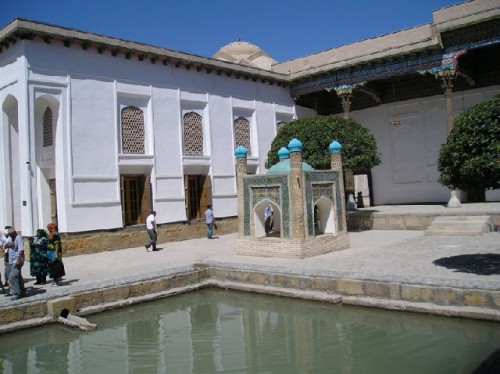

The necropolis of Bakhauddin Nakhshbandi, one of the founders of Sufic Islam, is a holy site. A rectangular yard with the sheik’s tomb forms the center of the complex, which has a mosque and dervish khanagha (hostel) with a huge dome on arches. Pilgrims circle and pray in front of the tombstone, tying rags, money, and written wishes around a tree said to have sprouted from the sheik’s staff.

The Chor Bakr Necropolis is another sacred place, where Imam Sayid Abu Bakr and his three brothers, direct descendants of the Prophet, were laid to rest in 970 in the village of Sumitan, seven kilometers west of Bukhara. The site gained immediate sanctity, attracting others, who claimed holiness by association. The complex includes a mosque, dervish khanagha, and madrassah around a central square. There is also a washhouse where pilgrims perform their ablutions. Decoration of the complex is sparse; tombs are in disrepair. However, the place still has an unrestored grandeur.

Tandir kebap (lamb cooked in a pit) with tomato salad was my choice for lunch. Having skipped fresh vegetables for a week, I decided to enjoy them regardless of the consequences. During a final walk through the Lyab-I Hauz square, I spotted a young girl with a red T-shirt bearing the crescent and star of the Turkish flag. Daring to try my Turkish, I approached her and introduced myself. She broke into a smile when she found out that I was Turkish. She and her family were leaving for Istanbul the next morning, she said excitedly. This was their first trip outside of Uzbekistan.

Likewise, I was excited about our trip to Khiva the next morning. Crossing the Kyzyl Kum (“Red Sand”) desert was our next adventure.

(To be continued)