BSO Porgy and Bess

Concert Version Conducted by Bramwell Tovey

By: David Bonetti - Sep 29, 2012

Porgy and Bess

Music by George Gershwin

Libretto by DuBose and Dorothy Heyward and Ira Gershwin

Based on a novel by DuBose Heyward and a play adapted from it by Heyward and his wife Dorothy

Concert presentation of original 1935 Broadway version

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Boston Symphony Hall

Sept. 27, 28, 29

Conducted by Bramwell Tovey

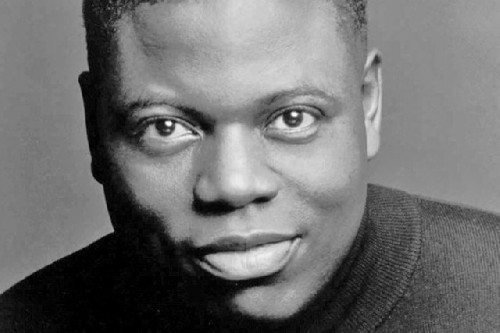

Cast: Alfred Walker, bass-baritone – Porgy, Laquita Mitchell, soprano – Bess, Gregg Baker, baritone - Crown, Jermaine Smith, tenor – Sporting Life, Gwendolyn Brown, contralto – Maria, Angel Blue, soprano – Clara, Marquita Lister, soprano – Serena, Alison Buchanan, soprano – Lily, Strawberry Woman, Ktysty Swann, mezzo-soprano – Annie, Calvin Lee, tenor – Mingo, Nelson, Crab Man, Chauncey Packer, tenor – Peter, Solo, Patrick Blackwell, baritone – Jim, undertaker, John Fulton, baritone – Robbins, Robert Honeysucker, baritone – Frazier, Leon Williams, baritone – Jake, Will Lebow, actor – detective, Patrick Shea, actor – coroner, Joel Colodner, actor – Archdale, Matthew Heck, actor – policeman, Jeffrey Toussaint, child actor – Scipio: Tanglewood Festival Chorus Conducted by John Oliver

The Boston Symphony Orchestra’s presentation of the so-called Broadway version of George Gershwin’s classic American folk opera “Porgy and Bess” is musically rich, bringing out the complexities of the score with a clarity that only underscores how great the work is. It is the first time the orchestra has performed “Porgy,” which opened in Boston in 1935 as a try-out for its New York premiere, in Symphony Hall. (It first performed the work, with essentially the same cast, last summer at Tanglewood.) The evening’s success might embolden the orchestra (or a local opera company) to present the full “operatic” version next time.

Still, have no doubt about it, even in the shortened version, this is an opera, not a musical or a revue of the type that dominated Broadway in the years before World War II, in which Gershwin made his name as a tunesmith. The radical formal nature of the work might have been overshadowed by its story of the struggling working-class inhabitants of Catfish Row, a black slum in Charleston, South Carolina; its all-black singing cast and the jazz and blues elements integrally incorporated in its orchestral score. All were novelties at the time.

The work’s operatic nature still causes fear and trembling in some quarters. Just over a year ago, Diane Paulus, the director of the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, prepared another “Broadway” version of the work, which did indeed play successfully in New York, garnering its Bess, an incandescent Audra McDonald, a Tony award for best actress in a musical. There were howls of protest about that production in advance of its premiere here – in effect, its second Boston try-out - but I found the results to be theatrically if not musically effective. The cast was uneven, mixing operatically trained singers with Broadway belters and crooners; sung recitatives of the original were turned into spoken dialogue, and, worst of all, it was all miked, a sure-fire killer of a true live music experience. Still, it worked on its own terms. And McDonald was electrifying.

The virtues and deficiencies are reversed in the BSO’s production. From the opening chords of the familiar overture – high-style New York jazz with a hint of southern blues, the staccato beats of the xylophone and percussion creating great anticipation of what’s to come – you know you’re hearing live music created by a great orchestra in the here and now. And all the singers were trained in the operatic tradition. Unaided by microphones, they were able to fill the 2,000 seat barn that is Symphony Hall with full, unmediated sound.

But dramatically, the evening was something of a dud. It was not as bad as I feared, certainly not as static as James Levine’s concert version of Bartok’s “Blue Beard’s Castle” last year, when the singers stood at the lip of the stage and sang in place. Here, the singers moved around; indeed, Jermaine Smith, an electric Sporting Life, twisted, shimmied, jive-danced and did a split, channeling the spirit of Cab Calloway, who played the role in one of its revivals. But the men all wore identical tuxedos which made it difficult to differentiate the large cast, many of which only have a few lines here and there, not to mention that some of them were multiply cast in minor roles.

One sensed that the cast was game for greater dramatic expression – the extravagantly pony-tailed Smith certainly was. It’s too bad they weren’t asked to do more to enact what was happening. (The addition of supertitles would have also made some of the ensembles more understandable.) An example: Clara sings the great lullaby “Summertime” to her baby, rocking him in her arms. Later she entrusts his care to Bess, who reprises the song. A prop, a doll wrapped in a blanket, would have gone a long way to explain to the audience that might not know the intricacies of the plot, why Bess is singing Clara’s song. Similarly, a knife in the two scenes in which a stabbing occurs could have explained a lot, especially during the orchestral rendering of Porgy’s stabbing of Crown. If you hadn’t read the plot summary, you would never have figured out what had happened.

But let’s take a look at what the BSO achieved. “Porgy and Bess” is known for its many great “songs” – they call them arias in opera. Out of context, “Summertime” has become one of the great American standards, sung by everyone from Ella Fitzgerald to Janis Joplin. But the BSO made you hear how it fit into a story, that it wasn’t just a Tin Pan Alley hit. The vibrant overture moves without a pause to an ensemble scene on Catfish Row, its many inhabitants conversing in short, overlapping lines, the chorus dominating the proceedings; suddenly, the hub-bub quiets, the strings, accompanied by oboe and harp, introduce a familiar, insinuating melody, a young woman rocks her baby in her arms and sings it to sleep. When she is finished, the action moves on seamlessly to the crap game that will end in the fateful stabbing by Crown of the man who beat him at the game. “Summertime” is not presented as a show-stopper – it is part of an organic whole from which it emerges and, when Clara has finished with it, it recedes back into the story. Gershwin’s compositional skills exhibited here are breathtaking.

The BSO’s respect of the text reminded me of Rene Jacobs’ recordings from a decade or so ago of the Mozart/da Ponte collaborations - arias that are usually recorded as showpieces were shown to be part of the dramatic and musical context. I wish there were more examples of such an approach, but the diva and divo-dominated tradition has distorted the intentions of many operatic composers.

In addition to the suppression of theatrical values, the greatest problem with the BSO presentation was an imbalance in forces. Both the orchestra and the chorus were enormous, overpowering the proceedings. The sumptuousness of the orchestral sound sought to align Gershwin with Strauss or Puccini, his slightly older contemporaries. The BSO seemed to have forgotten that Gershwin himself called “Porgy” a “folk opera.” A folk opera does not need a chorus of 100 and an even larger orchestra. It might have more fruitfully thought of the model of Kurt Weill’s “Threepenny Opera,” a work premiered only eight years earlier, based on a British ballad opera that is as close to a folk opera as you can get. A leaner orchestral and chorus sound would have allowed the singers to take a more dominant role.

Although the BSO did not have an Audra McDonald, a sui-generis phenomenon, it had a far better cast of singers than Diane Paulus’s apparently haphazardly cast ART production. For the most part, the male singers excelled, especially the basses and baritones, giving the singing tapestry a low register.

As Porgy, the cripple whose love for Bess is at the heart of the drama, Alfred Walker was the outstanding voice of the evening. Rich, resonant, articulate through all registers, his voice is major. He sings Mozart, Verdi, Wagner and Strauss in major houses here and abroad, including the Met and La Scala. He didn’t try to pretend to physically act. The drama was in the nuances of his singing. Bostonians should be cheered to hear that he is singing the Dutchman in Boston Lyric Opera’s production of Wagner’s “The Flying Dutchman” early next year. I can hardly wait.

Laquita Mitchell’s Bess was a mixed bag, perhaps a better actor than singer. When she entered with Crown, the thug whose woman she is until she meets Porgy, she is appropriately louche, but her voice is thin compared to her colleagues, and she stretches to hit the high notes. But maybe that is because she is playing a character addled by drugs. When she sings “I Loves You, Porgy” with Porgy – perhaps the greatest post-Puccini love duet in the repertory – she comes into her full voice and hits her high notes without struggling, her voice supported from below. All in all, she was a sympathetic Bess, dependent and confused unlike the assertive figure McDonald created at ART.

Jermaine Smith’s Sporting Life, the trickster who supplies the residents of Catfish Row with happy dust, i.e., cocaine, came close to stealing the show – okay, he stole the show. Smith has based his career on playing the role and his familiarity with it showed. He sang fluently with a beautiful tenor voice, and he moved with a dancer’s grace, bringing an understanding of African-American movement that most of the cast lacked – or didn’t have an opportunity to express.

As Clara, the woman who gets to sing “Summertime” and not much else, Angel Blue was the best female singer. In a reprise of her signature aria, she spins a gossamer line into the stratosphere that was breathtaking.

Serena, the woman whose husband Robbins is killed by Crown in the crap game, gets to sing one of the great laments in opera, a genre that goes back to Monteverdi and Purcell. Soprano Marquita Lister put over “My Man’s Gone Now” with the requisite feeling if not with an easy negotiation of her high notes, although her vocalize at the end was heartbreaking.

Of the principals, Gregg Baker’s Crown, the thug who bullies Catfish Row’s denizens at his pleasure, was the least persuasive. A physically powerful man, he entered with the menace the role requires, but he failed to project the same disruptive power in subsequent scenes. His baritone was powerful, but his acting was not. And in the “jazz” song, “A red-headed woman makes a choo-choo jump its tracks,” his one moment to let loose, he was surprisingly stiff.

As Maria, contralto Gwendolyn Brown was a hit. Playing the earth mother who does her best to hold the community together – Pearl Bailey played her in the Otto Preminger movie - compassionate but ready to judge the sinner, she got it all right.

The rest of the large cast was fine.

Bramwell Tovey conducted with verve and a total understanding of the complexity of the score, its rapid switches from late romanticism to jazz, its alternation of choral passages with lyrical song. He played the piano solo in the overture with a real sense of boogie-woogie swing.

The Tanglewood Festival Chorus under the direction of the estimable John Oliver was dynamic. Although because of its sheer size, it unfortunately dominated the evening, it was intended by Gershwin to play a central role in the drama like the choruses in the great Russian operas such as “Boris Godunov,” which he undoubtedly knew. As the voice of the community, it commented on what was going on and also voiced spiritual and communal values. Singing the original “spirituals” Gershwin composed, you’d think the chorus specialized in spirituals, rather than in Mozart, Berlioz and Brahms.

Some of Gershwin’s spirituals were so good – “Somebody Knockin’ at the Door” particularly – that you’d swear they were traditional. By the way, the opera as a whole abounds in different vocal genres. In addition to the spirituals, there’s the aforementioned love duet, lullaby and lament, street chants, blues songs, blues-inflected dances, Tin Pan Alley style popular song and a rollicking march. What American culture lost with Gershwin’s early death! The Metropolitan Opera had asked him to write an opera based on the Dybbuk, the Jewish folk tale, and you can imagine him setting tales of art deco New York.

Especially with the Paulus “Porgy” at ART, there has been a renewed discussion of the racism inherent in the Gershwins’ “Porgy and Bess.” To address that issue adequately would require lots more space than I have here. But college-educated African Americans of the 21st century who object to Porgy singing, “Bess, you is my woman now” rather than “Bess, you are my woman now” lack historical perspective. If the inhabitants of Catfish Row, only two generations out of slavery, who struggled to survive, had all gone to Princeton or at least to the local community college and learned to speak standard English, we wouldn’t have needed the Civil Rights movement. There is no more wasted energy than in trying to correct the faults of the past. The smart approach is to make sure they don’t happen again.

“Porgy and Bess” is filled with moments of “uplift,” the realistic if compromised philosophy promoted by Booker T. Washington that was all you could do during the era of apartheid. (Look at Aaron Douglas’s contemporaneous paintings.) “Going to the promised land,” “taking a boat that’s leaving soon for New York,” are references to escaping, which thousands of southern African Americans were doing every year during the 1920s. I like to think that the baby to whom Clara is singing, “One of these days, you’re going to rise up singing, you’re going to spread your wings and take to the sky” was Rosa Parks or her Charleston equivalent. The dates are right. “Porgy and Bess” was part of the struggle, not just a purveyor of stereotypes.