Kai Althof Institute of Contemporary Art

Kai KeinRespekt (Kai No Respect)

By: Charles Giuliano - Sep 26, 2013

Kai Althoff

Kai KeinRespekt (Kai No Respect)

The Institute of Contemporary Art Boston

May 26 to September 6

Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

September 23 to January 16, 2005

Curated by Nicholas Baume

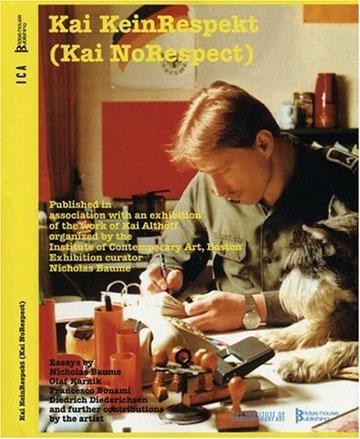

Catalogue, designed in collaboration with the artist, with essays by Baume, an introduction of ICA director, Jill Medvedow, Olaf Karnik, Francesco Bonami, and Diedrich Diederruchsen, as well as texts by the artist, exhibition history and bibliography, Published by Bridge House Publishing, Miami Beach, 120 Pages, illustrated, $35.

Pasiphae, the wife of Minos the king of ancient Crete, lusted for a bull which shunned her human form. Daedalus created for her a hollow cow inside of which she exposed her rear to be mounted by the raging bull. Thus was born a monster, the Minotaur. Minos confined the beast to the depths of a labyrinth designed by the ever resourceful Daedalus.

While pursuing a series of tasks as a rite of manhood the hero Theseus aspired to slay the Minotaur. To aid in this pursuit he was given a ball of string by Ariadne, a princess, whom he married but subsequently abandoned on the Isle of Naxos while she slept.

A tour of the exhibition of the Cologne artist, Kai Althoff, (born 1966) was amazing. Or more literally, feeling lost and jostled about in a maze. The attempt was to capture, slay, understand, assimilate the complex and daunting work of the artist. But entering into this Gesamtkunstwerk (Total Work of Art) there is a sensation of being engulfed, overwhelmed and disoriented by a chaotic installation of drawings, paintings, photographs, clips from vintage magazines, listening stations to hear the artist’s recordings, monitors of videos, and piles of as well as a room of stuff. The walls and stairs of the museum have been painted in a Constructivist scheme of the primary colors used by printers. They are also used as page backgrounds in the publication which follows a similar pattern. A corner of the second floor, triangled off with a glass wall allows a view of a trashed room, seemingly a vignette from a crack house or degenerate environment.

Slogging through a quagmire of the young artist’s daunting array of works in many media and styles, how then to find the thread to make one’s back out to the clear light of day and compose a succinct, rational report on this odyssey through the circles of heaven and hell. The range of experience, a deliberate assertion of the practice of the artist, recalls the chaos and ecstasy of a psychedelic experience of the '60s, or more appropriate to the artist age and milieu, some contemporary, trippy club drug.

Based on this glimpse into a potent and compelling view of the inner life of sonic German youth, the inner voyage of today is far more dark and foreboding, more noir. More evident of what we would have called a bad trip.

Add to that difficulty of comprehension is the separation of generation and geography. There is always the approach to art of viewing it from the inside out and then back again. We come to the experience through self, the sum of our interests and life experience. There is the egocentric barrier to be overcome in confronting new and challenging work. It is essential to find a commonality and connection. Just what do we bring to the experience that relates directly to the work. Where does the DNA chain match up? And, if there is no such point of contact, do we just pull back and disconnect.

For the average visitor to the ICA that may be a consistent response. But, for the art critic, there is no such escape. This is, indeed, a most important exhibition, the first museum level survey of a young artist who is widely influential among his European peers, and avidly sought after by gallerists and collectors. This is all the more compelling and ironic as the artist has mostly worked in a private and reclusive manner. He lives and creates in a small apartment making all his own pieces without assistants and with whatever material is at hand.

The catalogue essays state that the artist has often worked collaboratively and enjoys group dynamics. Toward that end he has invented varying personas that are often credited in his works and projects. They are fleshed out with ersatz lives and personalities. Some of them are modeled after well known scenes and moments of time in contemporary European culture. Mod London of the '60s and '70s, for example. The artist is described as being part of groups or cliques that agree to common positions and attitudes that include hanging out in clubs and bars. Much of this behavior conflates the boundaries between art and adolescence. It speaks to a time in our life and social development when it is imperative to have mates of like mind, the more strange and edgy the better. There is the importance of belonging even within informal structures.

While the response of many Boston visitors has ranged from confusion to apathy the global focus and attention for this event is enormous. During a recent week of visiting galleries in Vienna we were frequently asked if we had seen this show. There have been similar questions from gallerists and peers in the Boston arts world. Nobody seems to know quite what to make of the show but it has provoked pervasive interest and debate.

Again, this cuts to the issues of regionalism and provincialism. It applies to the idea of an audience and curators who do not travel much, or import challenging work and ideas. But, what is compelling about living and working in Boston is precisely the process of exhibitions such as this mounted by the ICA and other progressive institutions of which there are many, great and small. The universities and schools constantly bring challenging international ideas into the community. It is precisely why one becomes testy and impatient with dumbing down regional art.

None of which implies that I have a great grasp of the work of Kai Althoff and the rich and complex post war, devoutly Catholic underground, youthful counter culture of Koln. Truth is that I have not listened to the Krautrock, an influence on his music, and the mix of his group, Workshop. Like many international artists of his generation the focus shifts constantly from music, clubs, film/ video to painting, and installation. Art schools, for example, have been notable for spawning rock bands, like Talking Heads that came out of RISD. Nor did I spend serious time looking at the videos. Perhaps I will return on another summer day to put on the head phones.

Without getting into the music and videos there was enough to handle in the exhibition and its complex installation.

It is interesting and revealing that Nicholas Baume chose this project as his first for the ICA. In the catalogue, the design of which is as complex and inaccessible as the exhibition itself, he states that he had never met the artist when he approached him. The artist responded, oddly, that Boston held specific importance to him. Part of his work involves creating scenarios and narratives about places and periods of time. An element of the work, for example, evokes inventions about swinging London and an ersatz rock group and their identities.

Prior to this ICA show the artist had shown twice in New York galleries, in a drawing show at MoMA, and widely in Europe. So the work was out there and it is significant that Baume brought it to Boston and then Chicago.

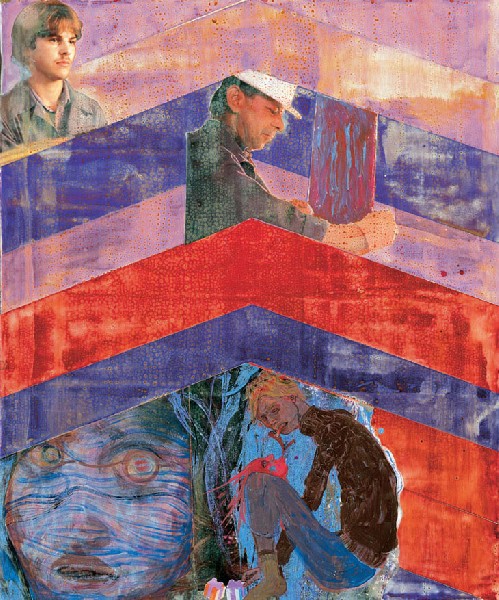

Part of that strategy and risk taking may involve a kind of rush to judgment, the bragging rights of being the first to mount a museum show. That may work well for the ambitions of the curator, a familiar tactic, but may also undermine the interests of the artist. Truth is, even though the exhibition represents an overview of some 15 years of production it is not correct to say that it congeals into a whole. It is more the element of many diverse and independent parts that add up to a not entirely connected whole. The eclectic, naive work and primitivist expressionist manner, with mostly dark earthy colors and murky washes, strikes me as more precocious than profound. It is difficult to determine whether the sketchy rough quality of the drawing results from deliberate style or a lack of formal training. This may be an instance of a very private, largely self taught, somewhat eccentric and fragile young gay man who has been probing deeply into his darkest inner most self now being forced out into the glare of the spotlight and celebrity.

There is the issue of art as commodity and consumerism. It subsumes main stream American art making. The most successful artists have found ways to surf on that wave of bigness, financial speculation and celebrity. Significantly,Julian Schnabel’s best recent work has been as a filmmaker. It is uncanny how many successful American artists see film as their ultimate extravagance. To go Hollywood.

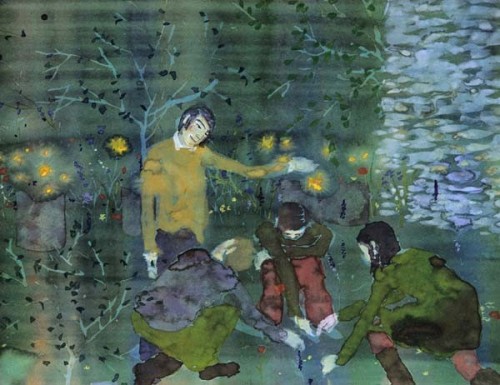

But coming to grips with Althoff requires abandoning the criteria of the American paradigm. It involves discarding Americentricity and adapting a Eurocentric view. But even that is not sufficient. This work is not so much generated by European or German culture, but more specifically, that of Koln. The complex city, leveled during World War Two, is dominated by its enormous cathedral and many Romanesque churches (rebuilt after the war). It is historically catholic compared to largely Protestant Germany. To become more deeply involved with Germany art and culture is to come to realize the great diversity of its regional character. So much is truly local. In his work, for example, that Catholicism becomes an important theme. Not that the artist is a practicing church going Catholic, but as is the case for many of us who have lapsed or not, the narrative and mysticism is deeply rooted. It is pervasive and inescapable.

So too, for Althoff is the richness and diversity of the German folk tradition of fairy tales, mythology and monsters. The artist is deeply involved in ways of penetrating and deploying that subculture. It pervades modern and contemporary Germanic cultures in the opera of Wagner, the literature of Herman Hesse, the obscure narrative, nationalistic themes of Anselm Kiefer and the confrontational works of Martin Kippenberger. But the difference here is Althoff’s privacy and intimacy the choice of modest scale and the avoidance of a German tendency for the epic and bombastic.

Like many Germans of his generation who have been inundated to the point of being fed up and blasé about their Nazi history, Althoff’s work reveals a fascination with introducing characters and narratives that include figures in uniforms from the wars. There are shocking images of sinster Brown Shirts tucked here and there into the drawings. A close inspection reveals examples of brutality and mutilation or incarnations of archetypical evil. One might imagine him undergoing a Jungian analysis. Not that artists seek to be cured. The work, however, may be a manifestation of a troubled psyche.

What is fascinating about the work is its focus on the Dionysian, the dark inner side. Again, this is deeply rooted in Northern European culture for which the Gothic horror, medieval war and plague are more resonant than the clarity and logic of the Apollonian Renaissance of the South. In that sense, Althoff’s work is staunchly expressionist and anti classical.

This work is very young. There is the element of the prodigy. It makes you question for how long it will sustain on raw nerve and self mutilation. Just how many young rockers and poets evolve to making mature work? Isn’t the usual tale one of tragedy and burn out? In this instance there is no coherent plan, strategy and style. No template for the future. The artist is consuming himself working on pure adrenalin. But that no tomorrow approach is precisely what gives it the critical edge of madness and daring.